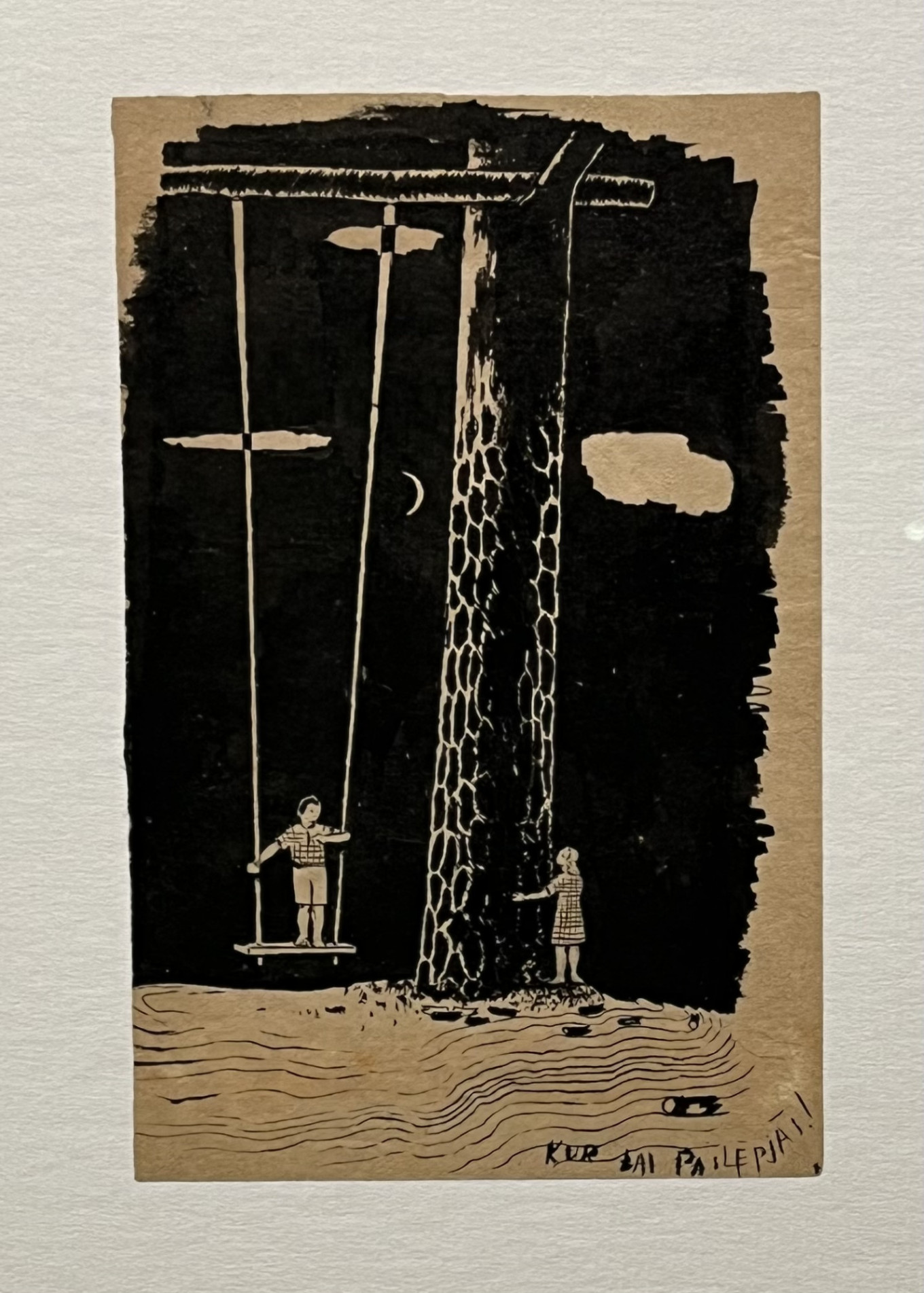

“Where to Hide” is a major new show of Latvian non-conformist art from 1945 to 1990 that opened in Riga. The name of the show is from a small drawing done by Roberts Stārosts in 1954. The drawing in India ink on yellowed paper is a scene at night: a sliver of moon hangs in the black sky beyond an enormous tree. A boy stands on a swing while a girl hides behind the tree. The title “Where to Hide” is written with either a slip of the pen or a slight grammatical error, as if the artist had begun to lose his native language during the decade of Soviet occupation.

It is one of several drawings of Stārosts on display, all of them depicting slightly mysterious scenes: a man pressed against the wall out of sight of a person looking out a window; a couple holding hands and gesturing at the night sky. The drawings pull you into a kind of retreat from the world off the paper that was, perhaps, no longer the world the artist had lived and worked in.

“Where to Hide” is a small work in a large exhibition of paintings, sculptures, posters, photographs, drawings, porcelain and a variety of applied arts done in the Latvian post-war, pre-independence period. It is being held in Zuzeum Art Centre, founded by art collector and philanthropist Jānis Zuzāns, who has the largest collection of Latvian art as well as non-conformist art from the other Soviet republics and contemporary art from around the world. The large airy space at Zuzeum, a former cork factory, is for now the main venue for contemporary art in the city, and the ideal space for this show.

By the time the Soviet Union made Latvia one of its republics, there was a more or less unified system for art education and production in the U.S.S.R. All of it was designed to produce artists skilled in the state style of socialist realism: images that were realistic and easy to understand, filled with socialist imagery. These are happy and heroic Soviet working-class people, well-fed and glowing with health, creating their rosy future on earth.

There were, of course, dissident artists who didn’t conform to these rules. The non-conformist movement has been well-documented, but as is so often the case in Soviet studies, the greatest attention has been given to Russian non-conformist artists, especially the artists who lived in and around Moscow.

Sandra Krastiņa, the curator of the show and an artist who was herself part of the non-conformist movement, told The Moscow Times that the arts system in Latvia was never as Orthodox as it was in Moscow. “In fact,” she continued, “a few years ago some curators had the idea of doing an exhibition of portraits of Stalin done in Latvia, but they couldn’t find enough to make a show.”

The Soviet Union formally annexed Latvia in August 1940, but “the occupation started after WWII,” Krastiņa said. “It was all very recent, not even recent memory — it had happened to our relatives, people we knew. The 1940s and war were filled with terror. Families had been sent to Siberia; we remembered when family members returned home.” The immediacy of experience was one of the factors that influenced art in this period.

In the Latvian art world the 1950s were still rather dogmatic, reflected in the show by paintings of workmen and posters of fresh-faced, blond young people looking off into the bright future. But by the 1980s when Krastiņa attended art school, “No one encouraged artists to take the ideological path. I remember when I had an offer to paint Lenin — I think it was 1984. I said I didn’t want to. But the ministry official said, ‘It might get you noticed!’ He needed to get someone to do this. He didn’t threaten. Instead, he tried to show the benefit: ‘Your work might end up at an exhibition’.”

The result, Krastiņa said, was dissident art that wasn’t always so radically different from official art. For example, Red Riflemen — elite Latvian soldiers who first fought in the Russian Imperial Army against Germany in 1915 and then joined the Bolsheviks in 1917 — were portrayed in official art as larger-than-life heroes. In 1971 painter Indulis Zariņš subtly undid the usually heroic image. His riflemen are portrayed riding home from battle through a stylized forest, not full of energy but hunched over, exhausted, on horses plodding ahead with fatigue.

Another characteristic of Latvian non-conformist art was a striving to reclaim their native culture. As Krastiņa writes in her introduction to the exhibition, these artists were using their “art as an instrument of unbounded information and action, as a kind of internal combustion engine for the staying power of national identity.” In 1962 Džemma Skulme painted several works like folk icons, one a triptych called “This is a Big Day for the Song,” calling to mind the country’s strong traditions of folk singing and music festivals. Another of her paintings, called “Folk Song,” is a very different kind of music — a dirge, perhaps. It was painted in 1969 in reference to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia that put an end to the Prague Spring. In the show it is exhibited close to the floor, as if the painting itself had fallen, forcing visitors' eyes downward.

In the 1970s a new kind of art appeared in Latvia — photorealism, exemplified in the show by a 1975 portrait of Vladimir Lenin by Miervaldis Polis. Technically superb, it is mesmerizing — visitors always stop and stand before it — and while it doesn’t seem daring today, at the time it broke all the canons of Soviet glorification of the founder of the Soviet state.

That same year Polis used the technique to paint eggs being cooked in actual frying pans, each precisely entitled: “Frying Pan with Eggs (not fried)”; “Frying Pan with Half-Fried Eggs.” It took more than a decade before they were exhibited.

What strikes the eye at the exhibition are explosions of bright, pure color and form, like Krastiņa’s enormous “Eater” and “Applauder” (1990) that seem so large and powerful the canvases can barely contain them. Or the massive and intriguing “Metaphor” done in 1966 by the artist Jānis Pauļuks. Children’s magazines are painted with brilliant primary colors. Porcelain tea sets are decorated with abstract splashes of color. Gauche drawings of fabric designs are like colorful rugs on the floor. Fashion posters are modernistic; sculptures are bold and expressionistic.

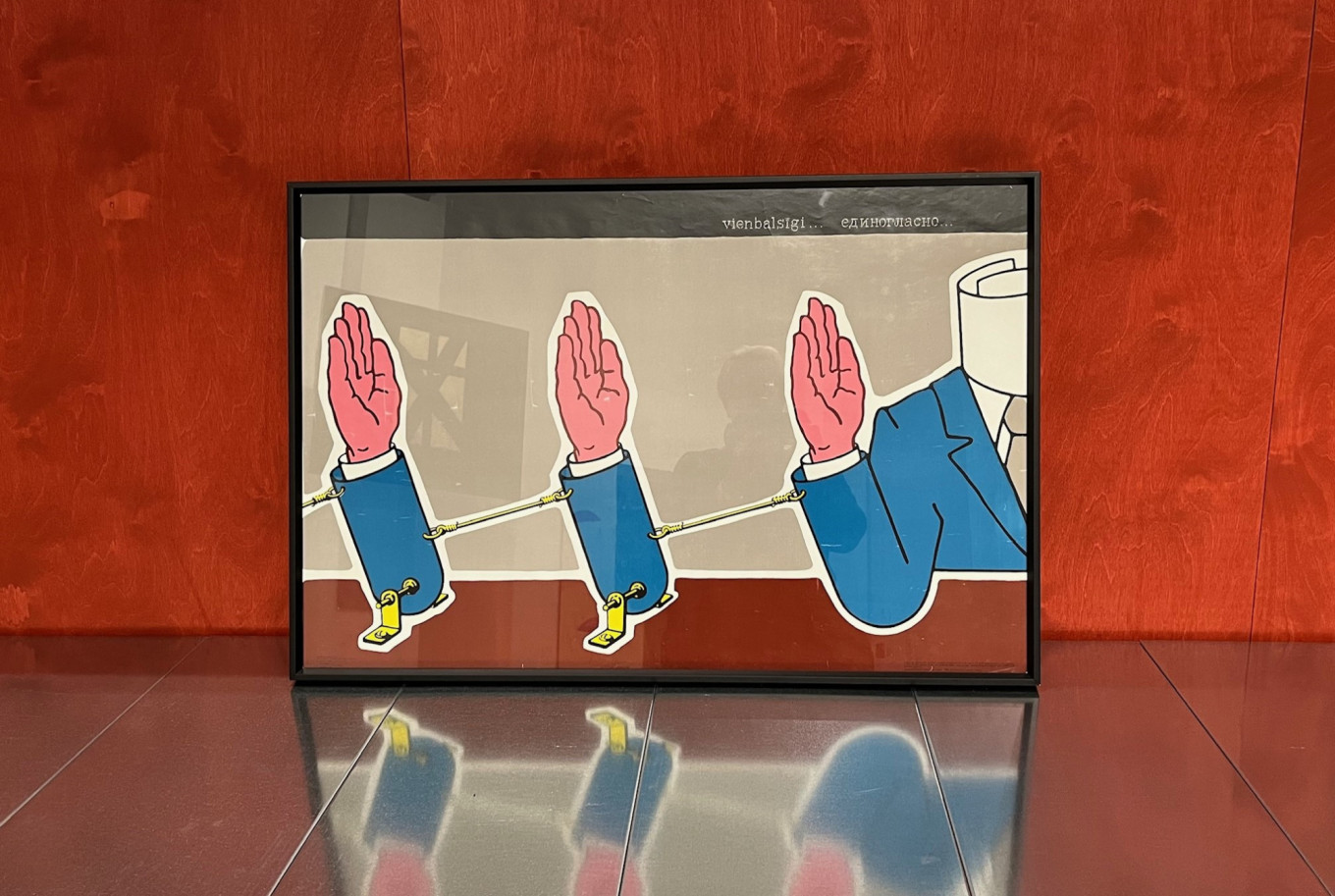

Some works are outright seditious, such as Pēteris Čivlis’ poster “Unanimously” done in 1988. But by then it was perhaps no longer dangerous; people could already hear the death knell of the regime.

The show will run until May 19, 2024. For more information about the show, artists and museum, see the Zuzeum site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.