Russian President Vladimir Putin was re-elected to a fifth term on Sunday in a landslide victory, following a three-day election panned in the West and criticized by independent election monitors.

The election was the eighth since the position of president of Russia was established by referendum in March 1991 amid the collapse of the Soviet Union.

1991: A Historic Victory for Boris Yeltsin

In June 1991, Boris Yeltsin, chair of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation, won Russia’s first presidential elections, defeating five other candidates with 57.3% of the vote (45,552,041 votes).

The ex-Communist democratic reformer defeated the Communist Party’s Nikolai Ryzhkov (16.85%), the Liberal Democratic Party of the Soviet Union’s Vladimir Zhirinovsky (7.81%) and three independents: chairman of the Kemerovo Regional Council of People's Deputies and people's deputy of the RSFSR Aman Tuleyev (6.81%), Colonel General and commander of the Volga-Ural Military District Albert Makashov (3.74%) and member of the U.S.S.R. Security Council and former Soviet Interior Minister Vadim Bakatin (3.42%).

Turnout was a high 75%, and Yeltsin, practically an incumbent, won with the backing of the political movement Democratic Russia.

His win was a victory for supporters of democratization — and decentralization, economic reform and free enterprise — over the nationalism of Zhirinovsky, softened by promises of cheap vodka, and over varying degrees of Communists encouraged by Mikhail Gorbachev to run and force Yeltsin into a runoff.

While not entirely fair, the 1991 election was the freest presidential election Russia has seen.

1996: The Beginning of the End of the Yeltsin Years

In June 1996, incumbent Boris Yeltsin won 35.28% of the vote (26,665,495 votes) in the first presidential election of independent Russia. This led to the first and so far only runoff presidential election in Russian history against the Communist Party’s Gennady Zyuganov (32.03%). On July 3, Yeltsin won a second term with 53.82% of the vote to Zyuganov’s 40.31%.

Yeltsin faced several challenges since 1991, including serious economic problems, a 1993 constitutional crisis that saw him use military force on the Russian parliament and expand his presidential powers, and the start of the First Chechen War. At the beginning of 1996, his approval rating was just 6%.

Eight other candidates ran in the first round: the Congress of Russian Communities’ populist General Alexander Lebed (14.52%), the liberal Yabloko party’s Grigory Yavlinsky (7.34%), LDPR’s Zhirinovsky (5.7%), the Party of Workers’ Self-Government’s Svyatoslav Fyodorov (0.92%), an independent Gorbachev (0.51%), the Socialist People's Party’s Martin Shakkum (0.37%), nationalist former weightlifting champion Yury Vlasov (0.20%), and the Socialist Party’s Vladimir Bryntsalov (0.16%).

In contrast to the 1991 election, the 1996 election saw significant pro-Yeltsin media bias and he was accused of using government resources in his campaign. Nonetheless, the number of registered candidates was indicative of the openness of the election, and there were relatively few problems reported in the voting process and vote count.

2000: The Putin Era Begins

Yeltsin would not complete his second term. He resigned at midnight on Dec. 31, 1999, handing the reins to then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

Early elections were scheduled for March 26, 2000, which acting President Putin won with 52.94% of the vote (39,740,467 votes) and Zyuganov again taking second place (29.21%).

Nine other candidates also ran: Yabloko’s Yavlinsky (5.8%), Tuleyev (2.95%), LDPR’s Zhirinovsky (2.7%), Samara Governor and independent Konstantin Titov (1.47%), For Civic Dignity’s Ella Pamfilova (1.01%), filmmaker and independent Stanislav Govorukhin (0.44%), scandal-plagued former Prosecutor General Yury Skuratov (0.43%), nationalist Spiritual Heritage’s Alexei Podberezkin (0.13%) and businessman Umar Dzhabrailov (0.1%).

Putin was widely expected to win, with some observers calling it a “coronation” rather than an election. Several candidates appeared to run for reasons other than gaining the presidency: Skuratov tried to improve his public image and Pamfilova, the first female presidential candidate, aimed to encourage women and independents to participate in politics.

Putin himself, backed by members of the Russian security establishment and newly popular for his response to a wave of purported Chechen apartment bombings across the country, hardly campaigned. He refused debates and election events in favor of glowing media coverage of his actions as acting president, including a 20% wage hike for teachers, doctors and other state workers just before the election. Still, there were relatively few election violations reported on election day and, with turnout at 68.64%, was considered relatively fair.

2004: Putin’s Second Term

Following economic successes in his first term and the overwhelming victory of his United Russia party in the December 2003 parliamentary elections, Putin won his second term in March 2004 with 71.31% of the vote (49,558,328 votes). He easily defeated his five competitors in an election one observer called a “one-man show.”

His opposition consisted of the Communist Party’s Nikolay Kharitonov (13.69%), moderate left candidate Sergei Glazyev (4.1%), liberal Putin critic Irina Khakamada (3.84%), LDPR’s Oleg Malyshkin (2.02%) and the nationalist but economically liberal Russian Party of Life’s Sergei Mironov (0.75%), who was considered a Putin loyalist.

Yabloko, which previously fielded the most prominent liberal opposition candidates, did not participate in protest of “the slide of the country into authoritarianism.” As in previous elections, there were irregularities noted in the North Caucasus, where officials admitted to stuffing ballot boxes, and state media strongly favored the incumbent.

International observers said the election was not “a healthy democratic election,” lacking “a vibrant political discourse and meaningful pluralism” and marred by instances of open and group voting and issues with vote counting.

The turnout of 64.32% was the lowest in the history of Russian presidential elections. Nonetheless, the results were indicative of continued high public support for Putin despite his continued minimalist approach to campaigning.

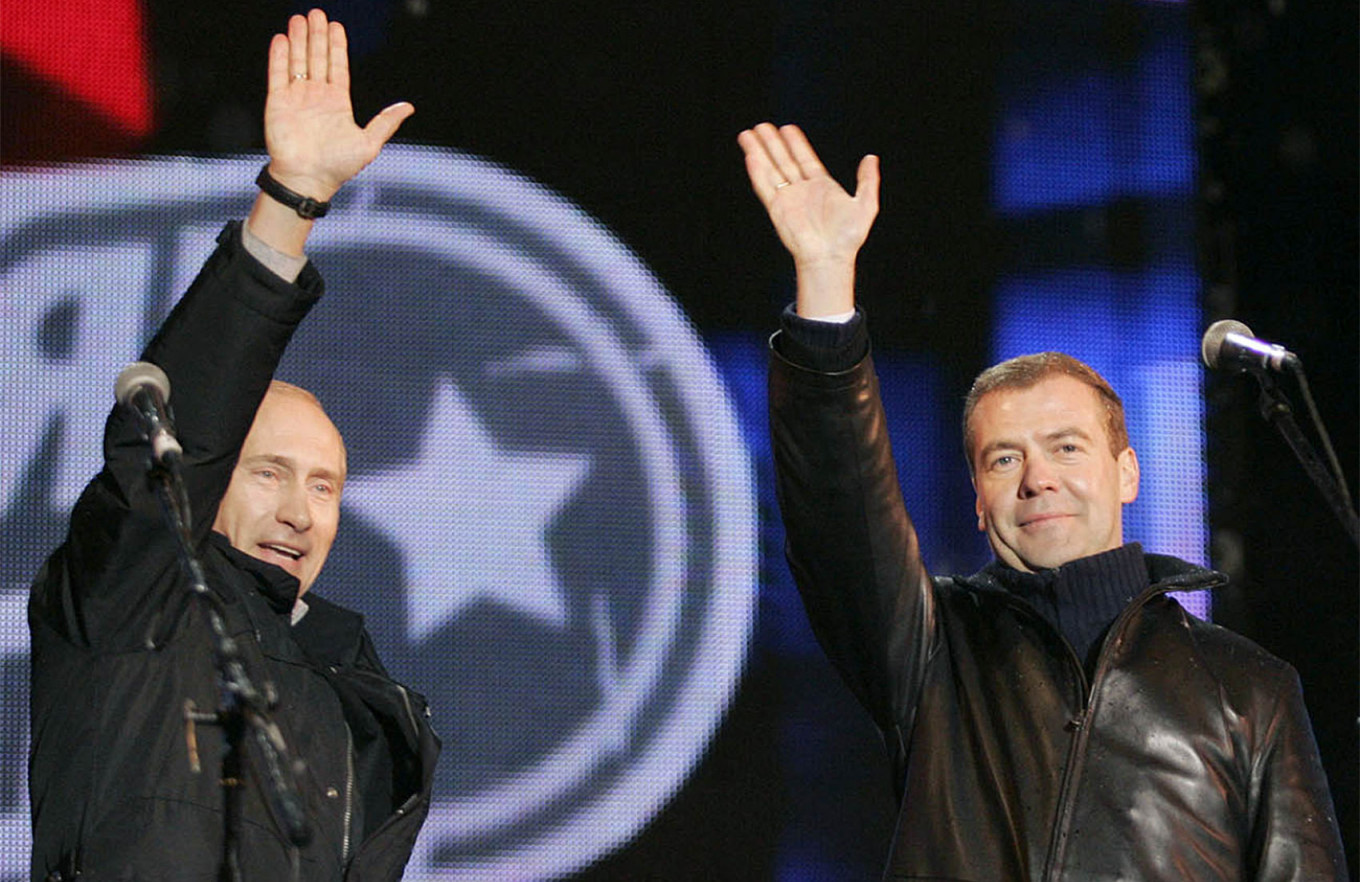

2008: The Medvedev Interregnum

Putin was constitutionally required to step down from the presidency at the end of his second term in 2008. His designated successor, Gazprom chairman and First Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, was nominated by United Russia and supported by several other parties including A Just Russia, the Agrarian Party, The Greens and Civilian Power.

On March 2, he won 70.28% of the vote (52,530,712 votes) in the country’s least free presidential election yet.

The opposition field had shrunk to an all-time low of three other candidates: Zyuganov (17.72%), Zhirinovsky (9.35%) and the Democratic Party’s Andrei Bogdanov (1.3%), who at 38 was the youngest person to ever run for the Russian presidency.

Chess champion and pro-democracy activist Garry Kasparov tried to run but ended his attempt after he was unable to rent a building in Moscow to hold a legally required nominating convention. He had also been jailed for five days and one of his organizers had been committed involuntarily to an insane asylum.

Former Prime Minister and People’s Democratic Union party nominee Mikhail Kasyanov also tried to run but was ultimately blocked by the Central Election Commission (CEC), who alleged that a large percentage of the signatures submitted to endorse his candidacy were “faked.” This technique would be regularly used in future elections to prevent opposition candidates from running.

The Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe canceled its usual election observation mission under onerous restrictions from the Russian government, while European observers present described the elections as “not free” and “not fair.” Public sector workers were threatened with job loss if they did not vote for Medvedev, who was strongly favored by Kremlin-controlled media.

After Medvedev’s ascension to the presidency, Putin maintained his grip on power as prime minister.

2012: Putin Elected for a Third Term Amid Protests

In March 2012, Putin was elected for a third term, defeating four other candidates with 63.60% of the vote (45,602,075 votes).

Zyuganov (17.18%) and Zhirinovsky (6.22%) ran once again, as well as independent billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov (7.98%) and socialist A Just Russia’s Sergei Mironov (3.85%).

As in past elections, the vote suffered from unfair media coverage and state resources used for the incumbent’s preferred candidate, as well as overly restrictive candidate registration requirements, which prevented the only liberal opposition candidate, Yabloko’s Yavlinsky, from running. There were also reports of ballot stuffing, carousel voting and widespread counting irregularities.

“There was no real competition and abuse of government resources ensured that the ultimate winner of the election was never in doubt,” an OSCE observer said.

Medvedev’s presidency saw Russia suffer the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis and a growing protest movement sparked by fraud in the December 2011 legislative elections.

Large-scale protests “For Fair Elections” were held before the election. A demonstration in Moscow before Putin’s inauguration drew a crowd of 20,000 and resulted in hundreds of arrests. A 15-day jail sentence would bring anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny new prominence.

Opposition leader Boris Nemtsov described Prokhorov’s candidacy as an attempt to distract the attention of liberal protesters, stopping “the wave of popular dissent” in order “to preserve Putin’s regime.”

During Medvedev’s time in office, the Constitution had been amended to extend presidential terms from four to six years, postponing the next election to 2018.

2018: Putin Elected With Highest Percentage to Date

Putin faced a more crowded field in 2018 but still easily won his fourth term as president, with 76.69% of the vote (56,426,399 votes), the highest share of votes in the history of the presidency yet.

His opposition consisted of former United Russia member and Communist Party nominee Pavel Grudinin (11.77%), LPDR’s Zhirinovsky (5.65%), Civic Initiative’s Ksenia Sobchak (1.68%), Yabloko’s Yavlinsky (1.05%), the economically right Party of Growth’s Boris Titov (0.76%), Communists of Russia’s Maxim Suraykin (0.69%), and Russian All-People's Union’s Sergei Baburin (0.65%).

Seventeen would-be candidates were rejected by the CEC, most notably Navalny, who planned to run on an anti-corruption platform and was barred based on a criminal conviction widely seen as politically motivated. He subsequently called for a boycott of the election.

Several candidates were perceived as “spoiler” candidates allowed or even encouraged by the Kremlin to participate to dilute the opposition’s votes — Sobchak to split the liberal opposition and Suraykin to draw votes from the Communist Party.

As with the previous election, observers found the election lacked “genuine competition” and reported ballot stuffing, carousel voting, suspicious turnout levels and other irregularities. One statistician estimated that these tactics added 10 million votes to Putin’s tally.

Putin’s third term had seen continued anti-corruption and anti-war protests, involvement in the Syrian Civil War and increased sanctions and tensions with the West amidst the Skripal poisonings and allegations of interference in the 2016 U.S. election.

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 boosted Putin’s popularity at home, while Russia’s unpopular 2018 pension reform was perceived as having been hidden from the public until after the election.

2024: Putin and His War Enshrined With New ‘Record’ Vote Margins

After a 2020 constitutional reset of his presidential terms, Putin was re-elected to a fifth term with 87.28% of the vote, the CEC announced Monday. His rule will continue until at least 2030, making him Russia’s longest-serving leader since Catherine the Great.

The Kremlin sought to secure historic vote counts for Putin and overall voter turnout in the election — and painted the results as a show of Russia’s national unity behind Putin and his invasion of Ukraine.

His victory was never in doubt, with all his major opponents dead, in prison or exiled, all the while the Kremlin has waged an unrelenting crackdown on public criticism of the war in Ukraine.

Three figurehead challengers, Communist candidate Nikolai Kharitonov, New People candidate Vladislav Davankov and nationalist Leonid Slutsky, all failed to receive over 5% of the vote.

Independent election watchdog Golos called the election an “imitation,” with widespread reports of vote tampering, restrictions on monitors and pressure on voters.

The three-day vote was also held in Russian-occupied parts of Ukraine in what the Kyiv and West deemed a sham.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.