Russia’s most prominent opposition figure Alexei Navalny died on Feb. 16 in the Arctic penal colony where he was serving a 19-year prison sentence, dealing a major blow to the country’s beleaguered opposition.

Ahead of next month’s presidential election, which President Vladimir Putin is expected to easily win, Russia’s opposition is divided more than ever before — both physically, by prison and exile, and politically, by disagreements over a slew of issues.

Here’s an overview of some of the opposition figures who could potentially take the lead following the loss of Navalny:

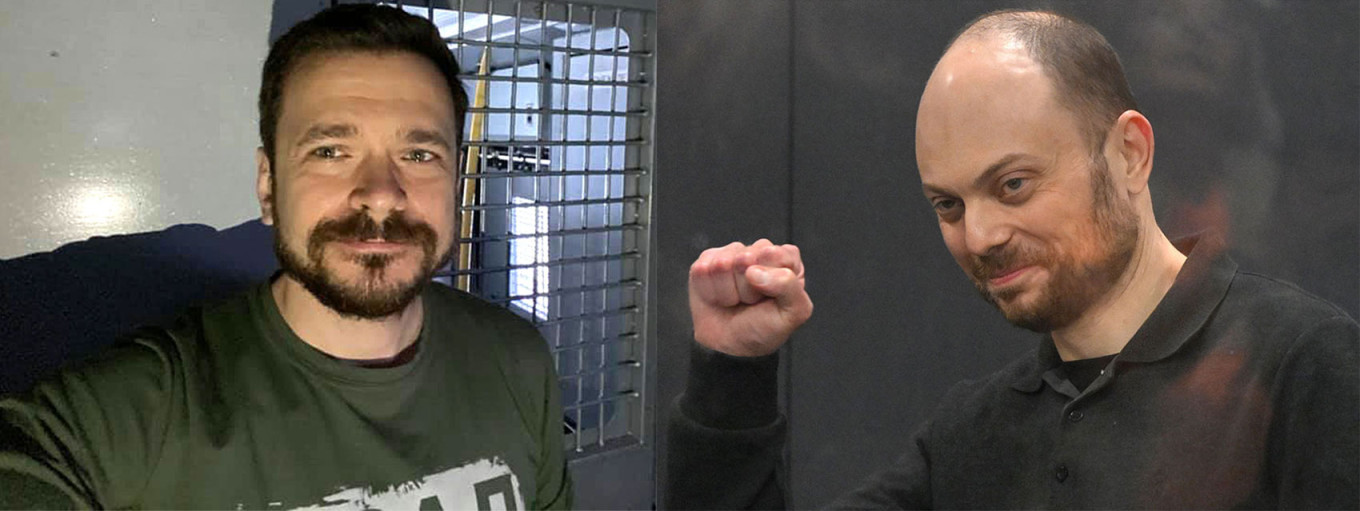

In Russia, but in prison: Ilya Yashin and Vladimir Kara-Murza

Vladimir Kara-Murza and Ilya Yashin are just two of the many activists and opposition figures currently behind bars for speaking out against the Kremlin or the war in Ukraine.

Journalist and Kremlin critic Kara-Murza is currently serving a 25-year sentence on treason charges related to his work on the Global Magnitsky Act, which has allowed the U.S. and allies to sanction government officials worldwide who are human rights offenders.

Throughout his career, Kara-Murza has come up against many of the same challenges faced by Navalny during his lifetime, including electoral losses marred by fraud, poisonings, decades-long prison sentences and deteriorating health while in prison.

Opposition politician Yashin, meanwhile, is serving eight and a half years in prison on charges of spreading false information about the military after he said Russian forces were behind the massacre of civilians in the Ukrainian city of Bucha.

Yashin, whom Navalny described as his “first friend in politics,” joined the liberal Yabloko party in 2000 and is known for being relatively mild-mannered and untarnished by the nationalism of Navalny’s earlier years.

In his final statement in court, Yashin said: “I must remain in Russia, I must speak the truth loudly.”

In Exile: Maxim Katz and Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Exiled opposition activist Maxim Katz and ex-oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky are among the Kremlin’s more prominent critics in exile, working from their respective bases in Israel and Britain.

Khodorkovsky — believed to have been the richest person in Russia when he was sentenced to prison on politically motivated fraud charges in 2003 — has used his wealth to fund the pro-democracy group Open Russia and several online news outlets over the past decade.

Katz, whose YouTube channel has over 2 million subscribers, met with Khodorkovsky last year as part of his efforts to unite the opposition. His ambitions to build an opposition coalition have so far been hampered by tensions with Navalny and his team, as well as his reputation for being difficult to work with.

“I have always called for a coalition because, among other reasons, I knew just how vulnerable individual opposition leaders are,” Khodorkovsky told The New York Times. “A coalition is much more stable as a system because if one person is gone, others are left.”

Would-be presidential candidates: Boris Nadezhdin and Yekaterina Duntsova

Boris Nadezhdin of the center-right Civic Initiative party and Yekaterina Duntsova, a journalist from the Tver region with no party affiliation, both drew attention with their pro-peace campaign platforms — but election authorities blocked both from the ballot.

Duntsova, a single mother of three with no national political experience and a carefully worded “pro-peace” agenda, was barred from running over alleged document errors. She was detained and drug tested in January after leaving a meeting to set up an organizing committee for a new political party. She says the party, called Rassvet (Dawn), will be “a party of all who stand for peace, freedom and democracy.”

Nadezhdin drew the support of tens of thousands in Russia and abroad, with footage of long lines of people waiting to endorse his candidacy flooding social media last month. While some saw endorsing him as their only way to express opposition to the war, others saw him as a real alternative to Putin.

Although Nadezhdin collected 150,000 signatures as well as endorsements from Duntsova, Katz, Khodorkovsky and some Navalny allies, he was blocked from running over alleged errors in his signatures. He is currently challenging his disqualification in court.

In Russia, under pressure: Yulia Galyamina and Yevgeny Roizman

A few openly Putin-critical politicians remain free in Russia, including ex-Yekaterinburg Mayor Yevgeny Roizman and linguist and former Moscow City Duma deputy Yulia Galyamina.

Galyamina had her jaw broken by police while protesting in 2017 and campaigned against 2020 constitutional changes that allow Putin to stay in power until 2036. She was recently fired from her teaching post because of her “foreign agent” status.

Her current project, “Soft Power,” trains women for leadership roles and organizes strikes and petitions. The group's anti-mobilization campaign in 2022 collected 500,000 signatures.

Roizman, once Russia’s highest-profile opposition mayor and a friend to Navalny, was fined in May 2023 for criticizing the war in Ukraine in a YouTube video. He remains popular in his home city of Yekaterinburg but has kept a low profile since his relatively lenient sentencing.

When he resigned as mayor in 2018 to protest increasing Kremlin control over mayoral postings, he said: “It’s easier to control people who are poor and beaten up than those who are prosperous and free.”

Navalny’s team: Leonid Volkov, Lyubov Sobol, Kira Yarmysh

Some of Navalny’s associates have become well-known figures themselves, including his longtime spokeswoman Kira Yarmysh, aide Lyubov Sobol and former Anti-Corruption Foundation board chairman Leonid Volkov.

Volkov spent roughly a decade in opposition politics, including as the head of Navalny's 2013 Moscow mayoral campaign and 2018 presidential campaign, before leaving Russia for Lithuania in 2020. Despite his political acumen, Volkov stepped down as ACF chairman last year after it was revealed that he had asked the EU to drop its sanctions on oligarch Mikhail Fridman.

Yarmysh, who is also a writer, is younger and has not been involved in any controversies. She fled Russia for Europe in 2021 following multiple jail stints for tweets and organizing protests. As Navalny’s spokesperson, her statements have focused on his death and his funeral plans; she has not indicated what she will do next.

“Historical justice is on our side. Putin is old. His regime is obsolete. It will definitely go,” Yarmysh told The Guardian last year. “Something new and bright will come instead.”

Sobol, a politician and lawyer with a popular YouTube show, rose to prominence in 2019 when she went on a hunger strike after being barred from running in Moscow’s local elections. She has been described as having “an anti-charismatic charisma.”

“I have never had rose-tinted glasses about any of this,” Sobol told The Moscow Times in 2018. “I understood in 2011 what the dangers were, and I am clear about them now. Of course I am scared for my daughter, but that’s why I am working here: to leave her with a better country to grow up in.”

Yulia Navalnaya

Navalny’s widow once said she was not interested in becoming another Sviatlana Tsikhanouvskaya, who became the leader of the Belarusian opposition after her husband was imprisoned, preferring instead to focus on being a mother and a wife.

However, her actions after Navalny’s poisoning in 2020, when she fought for his evacuation to a hospital in Germany, and her teary-eyed but confident speech at the Munich Security Conference after Navalny’s death was announced led many to speculate about her political future.

And though she preferred to stay out of politics, she played a major role by offering Navalny advice and guidance behind the scenes.

In a video statement released Feb. 19, she confirmed she would carry on her late husband’s work.

“I have no right to give up. I will continue the work of Alexei Navalny. I will continue to fight for our country and I urge you to stand next to me.”

She has since met with European Union leaders in Brussels and addressed the European Parliament in Strasbourg, where she urged European politicians to “investigate” the Western assets of Putin and his inner circle.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.