VILNIUS, Lithuania — Hundreds of Russian emigres gathered in central Vilnius to mourn the late Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny, with many expressing a mixture of anger, sorrow and helplessness.

In Lithuania’s capital, a hub for exiled Russian activists, the death of Russia’s most prominent opposition figure in prison has cast a heavy shadow.

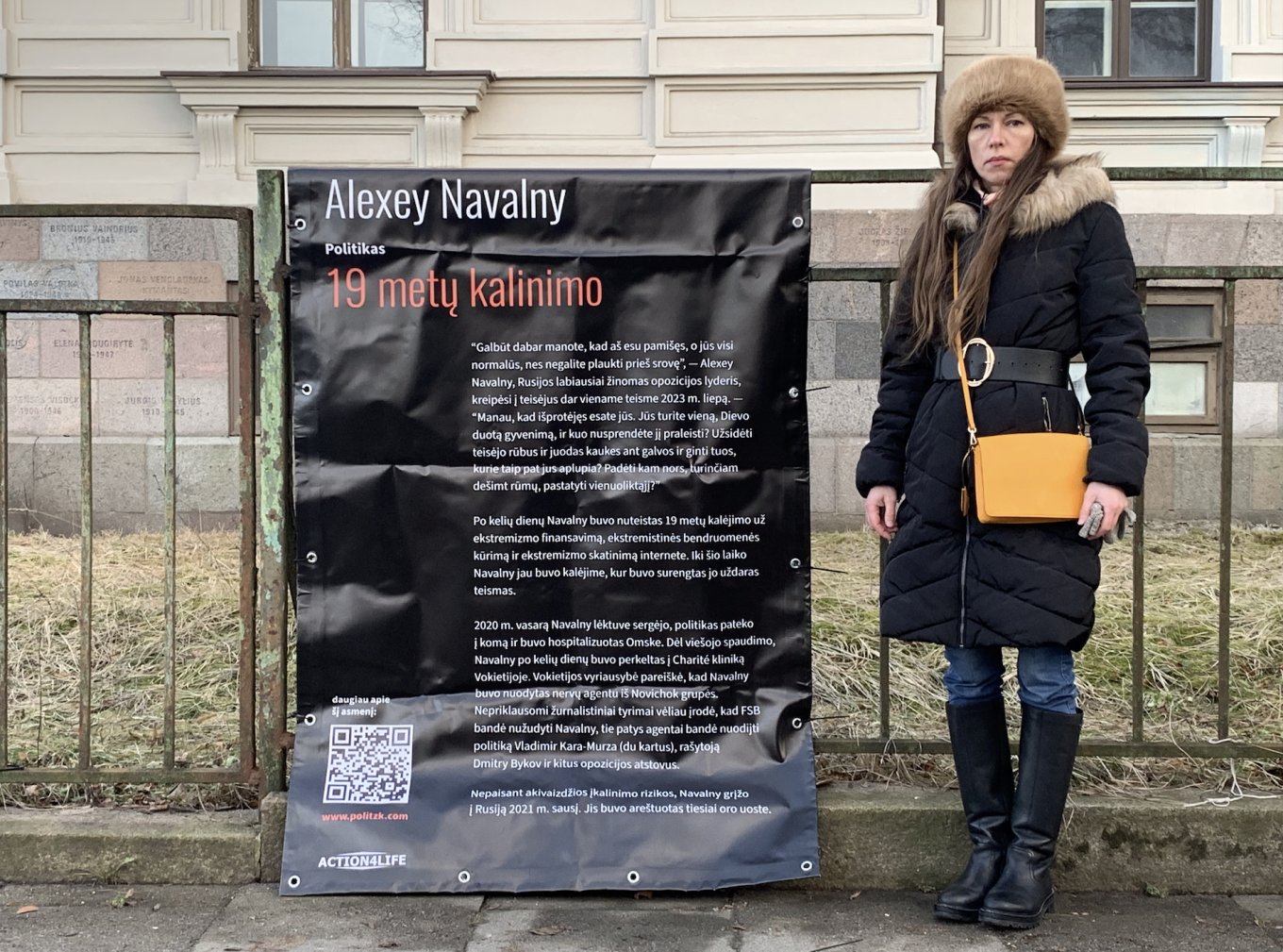

According to Lithuania’s national broadcaster LRT, some 500 Russians gathered at the monument to victims of the Soviet occupation on the city’s main artery Gediminas Avenue to mourn Navalny’s passing.

Mourners started coming to lay flowers at the memorial as soon as the news of Navalny’s death broke on Friday. These flowers slowly began to engulf the base of the occupation monument as the day progressed.

Among the mourners was former Moscow city council member Yelena Kotenochkina.

“I couldn’t believe that this has happened,” Kotenochkina said, who brought an art piece from the “Faces of the Russian Resistance” exposition she organized during the fall of 2023. “When Boris Nemtsov was murdered and I saw his body, I also couldn’t believe it.”

“I believe the reaction to [Navalny’s death] will be resolute — both among the opposition and ordinary Russians, even the ‘apolitical’ ones,” she added.

Kotenochkina proposed backing Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s idea to write Navalny’s name on the ballot in the March Russian presidential election. But otherwise, she said she believes that the immediate future has become way more uncertain.

“We are facing a new reality,” she said, explaining that in the past the opposition “could hope that Navalny would be released before his prison term was set to end. We hoped he would be the person to drive reforms” in Russia.

“Now we need to find another way to unite.”

“But that’s the future … We must live through today for now,” Kotenochkina said, taking a brief pause to stop herself from crying.

Despair and rage

By the time the rally was officially scheduled to begin, the crowd had grown so large that the monument could no longer be seen from the street.

Despite the large numbers, those attending the demonstration stood in silence, holding their phone flashlights in the air. Many had tears in their eyes. The mood was a mixture of anger and despair.

“A couple of weeks ago, I was at another demonstration dedicated to Navalny. Back then, I was holding a poster saying ‘Putin is a murderer’,” Dmitry Kuminov, one of the co-founders of the independent Mediazona news website, told The Moscow Times.

“Unfortunately, this poster couldn’t be more relevant today.”

“Political assassinations, war, the endless violence accompanying Russia’s repressive political system… Right now, I feel there is no way I can stop all this. Maybe I will, but today, I am in a state of utter powerlessness.”

Pussy Riot member Aysoltan Niyazova, who served a six-year prison term in Russia, said she felt “rage and pain from understanding that I can’t do anything to fix [Navalny’s death].”

“We are living through a shared grief,” she told The Moscow Times. “It doesn’t hit as hard when you are not alone. At the very least, we can all give each other a hug right now.”

Lawyer Dmitry Zakhvatov, known for defending detained Russian protesters, said he was enraged by Navalny’s death and called for all those complicit in political repressions inside Russia to be brought to justice.

“One day justice will prevail. When Russia finally becomes free, we must make sure that everybody involved in political repressions and assassinations is brought to responsibility. All of them — from the judges and prosecutors to those who were bringing them coffee or pizza.”

Zakhvatov said he believed Western governments did not do enough to punish the Kremlin after Navalny’s poisoning in 2020, and then his imprisonment the following year.

“I remember one European politician announcing that ‘they were concerned.’ And that’s it, nothing else,” the lawyer said.

“It was clear from that point that all the horrors we’ve experienced [since those statements] would happen, one after another,” he said, referring to the invasion of Ukraine and escalating political repressions in Russia and Belarus.

Street artist Philippenzo, who left Russia for Lithuania after facing prosecution for his anti-war graffiti, said he felt “rage” was “breaking out inside” of him.

“I am certain that millions of people around the world are feeling this moral outrage right now, and it can hardly be suppressed.”

‘He was like a brother’

As the crowd continued to grow, a mourner who brought a set of loudspeakers played the song “Hi, It’s Navalny,” written by the Russian ska-punk group Elysium.

Anastasia, a student from Russia who asked to change her name because of safety concerns, came to the memorial after finishing her shift at a local coffee shop.

“We’ve lost the one charismatic person who could unite the entire Russian opposition. I feel ashamed — we abandoned him, we didn’t manage to get him out,” she said.

“I’ve never seen Navalny in person, and yet I feel as if I’ve lost a relative.”

Throughout the day, dozens of Lithuanians stopped by the memorial to speak with mourning Russians and offer sympathies.

Robertas, who asked not to disclose his surname due to safety concerns, said he took part in the 1991 Vilnius television tower defense, a key event in Lithuania’s struggle for independence from the U.S.S.R. Soviet troops opened fire on unarmed Lithuanian protesters defending the tower, resulting in 12 deaths and hundreds of injuries.

Robertas told The Moscow Times that it made sense for anti-war Russians to commemorate Navalny at the memorial for victims of the Soviet occupation.

“I feel for these people, just like they did for me, for us [Lithuanians] in 1991 when they came out to Red Square to support us.”

His views on Navalny echoed those of Anastasia the student.

“It might sound absurd, but Navalny was closer to me than some of my actual relatives,” he said. “He was like a brother — not by blood, but a brother in arms, and that’s all that matters.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.