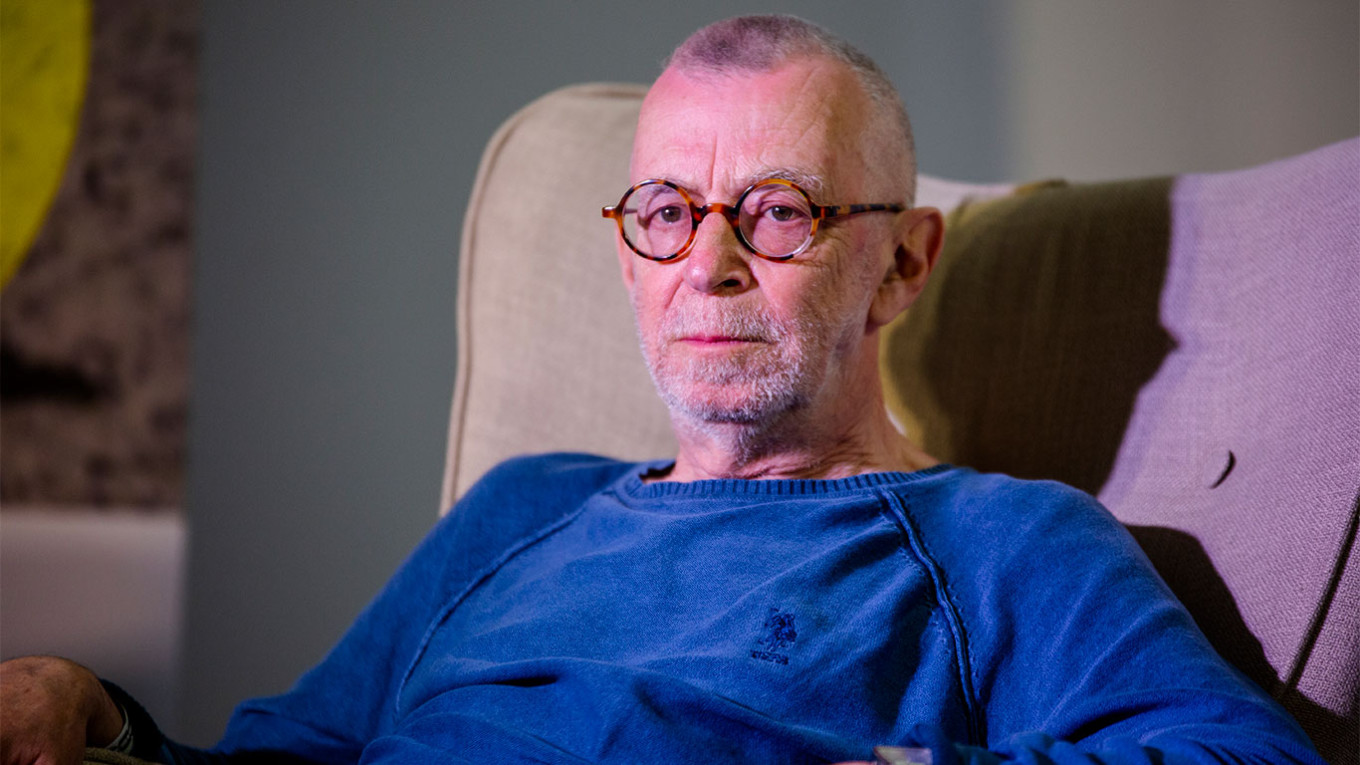

Lev Rubinstein, the legend of the Moscow conceptualist movement, the inventor of a unique way of writing, died on January 14, 2024. His life seemed as endless as his long poems and ended just as abruptly as they did — mid-word, on an ellipsis. This death devastated the Russian cultural community. Let us try to understand why.

Rubinstein's biography is a fusion of the Soviet and the anti-Soviet. He often shared his memories, emphasizing that he had lived a typical life for his era. He was born in 1947 to a family of a teacher and an engineer and spent his childhood in a communal apartment. His parents were "typical Komsomol members of the 1930s"; they trusted the authorities, despite their hard life.

His father went through the war from the first to the last day. His mother never ate macaroni, because in the 1930's during the famine in Kharkiv that’s all she had to eat for an entire winter. Rubinstein was six years old when Stalin died. In many of his interviews and essays, he recalled that on that day he was getting over another bad cold, and the association with recovery stuck for life.

Rubinstein's poetic aesthetic grew right out of his anti-Soviet ethics, and in the most literal sense. Not wanting to fit into the system and make a kind of career in the U.S.S.R., after graduating from a pedagogical institute Rubinstein took a job in a library. To practice writing, he made spontaneous notes on library catalog cards which were always at hand, and one day he decided that a poem could be a kind of card catalog.

His first poetic card catalogs appeared in the mid-1970s. Each card had a seemingly random text written on it, but together they lined up into an exquisite conceptual score. It was a brilliant example of the harmony of form and substance: did the card catalog perfectly embody this chosen style or did the style dictate the catalog? Each card was a stanza, which made the stanzas much more isolated and independent than in a poem written in the usual way. At the same time, each card always belongs to the whole card catalog, which prevents the text from completely falling apart. Rubinstein performed by moving the cards around, playing with different intonations, sudden changes of subject. Cards made the text physical, which opened up space for various tricks: shuffling stanzas into different orders, visualizing pauses (a blank card) and highlighting stage directions, passing the poem to the audience to create a joint reading.

Rubinstein's main study was the language of the Brezhnev era, now famous for its bureaucratese and streamlined meaningless phrases. Anthropologist Alexei Yurchak in his book “Everything Was Forever Until It Was No More,” characterized this language as totally hollow. Speaking at a Communist party meeting, one had to speak so that the words had no meaning at all. According to Yurchak this linguistic practice created a sense of the regime's stability, while in reality it undermined it.

“The unanimous participation of Soviet citizens in the performative reproduction of speech acts and rituals of authoritative discourse contributed to the general perception that the system was monolithic and immutable,” he wrote, “while at the same time enabling diverse and unpredictable meanings and ways to live to spring up everywhere within it.” This total performance made it almost impossible to imagine that the Soviet Union could suddenly collapse, but these new meanings and ways to live were making the system “vulnerable to a sudden implosion.’’

It turns out that poets and conceptual artists, in particular Lev Rubinstein, played the role of ideological saboteurs even as they were not aware of it. Rubinstein later always emphasized that while he sympathized with dissidents, he never set himself the mission of overthrowing the regime. He did not realize that very soon there would be no more Soviet state, and his strategy was just to create as much distance from it as possible and not participate in it.

The literary method he devised was also essentially a way of escaping totalitarian control and falsity. First of all, the library catalog cards were a way to publish poetry which couldn’t be officially published at that time. But most importantly, the author transformed bureaucratic formulations into a new context, which completely changed their content, in this way reappropriating, reclaiming the language usurped by the authorities. Rubinstein built thought constructs out of stock phrases, balancing on the boundary between complex reflection and sarcasm.

"At the present moment we are interested only in the present moment, along with everything which is connected with it."

"You can classify events from the point of view of their predetermined outcome."

"You will inevitably approach the moment when all of this will decisively lose all meaning."

In addition to the official language, the vortex of this poetics sucked in all kinds of lexical garbage floating around: worn-out school quotes from classics; captions to old photographs; technical instructions for new electronic gadgets; words endlessly coming out of the built-in kitchen radio; comments by neighbors in a communal apartment or in a grocery line. Once in the cards, Soviet reality was transformed into radically non-Soviet poetry. These experiments long anticipated many formats now popular in Russian contemporary art: documentary theater, found poetry, and narrative poems as long as short stories.

Rubinstein compiled his poetry catalogs until the mid-1990s. But with the end of the Soviet regime, the need for so-called "uncensored poetry" also ended. Although he sometimes returned to poetic texts, the creator of card-catalog lyrics largely switched to essays and opinion writing. Throughout the post-Soviet years, Rubinstein was published in various well-known socio-political media.

In the 2000s he became a consistent critic of Putin, condemned military aggression in Georgia and Ukraine, actively participated in protests, worked with the human rights organization Memorial, attended political trials, and spoke out in support of Pussy Riot, Navalny, and others. His once principled indifference to politics was replaced by the completely opposite behavior — everyday eager involvement in the issues. However, Rubinstein continued to do what he always did: he passionately studied the Russian language. His articles were not just characterized by a special attention to it; often they were entirely based on linguistic observations.

After the full-scale invasion began, Rubinstein was one of the most prominent oppositionists who did not leave Russia and openly condemned the war. "The idiotic forced monkey-like militarism of recent years, which is then massively encouraged and fueled from the television screen, is not such a great surprise to me,” he wrote, “because oddly enough I see myself in these people shouting ‘We’ll Show You Like We Did Before.’ Yes, myself. And also my friend Sasha Smirnov. And also my friend Yura Stepanov. And also some other friend, whose name I have forgotten, but I remember only that he was a friend for life. I recognize us. But us at the age of about eight. At most, nine years old, and not a day older.” And after there is a description of the boys sitting on a "sun-warmed shed roof," munching on unripe sour apples and discussing how great it would be to be victorious over everyone again.

Rubinstein liked to say that history does not repeat itself, but it often is harmonious and rhymes. He considered today's atmosphere with its hopelessness to be consonant with the atmosphere of the first half of the 1980s. He sympathetically explained that it was much easier for him to experience this than for young people now. Rubinstein was very active: he performed in clubs, gave interviews, attended events, appearing everywhere like an invulnerable god of linguistic disobedience and enlivening everyone by his mere presence. He said that, according to his experience, it is possible not only to survive in a monstrous environment, but even to create independent art. That everything ends one day and sometimes it happens much faster than you imagine.

His remarks were always impeccably in his own style, and he called on people to "find adequate forms of compassion for each other." When someone sought advice on what to say to their mother, with whom there had been a breach over political views, the reply was: "Say: ‘Mom, cook me something delicious today’." When he talked about emigration and the pain of parting, he encouraged people, reminding them that in Soviet times it was much harder. Then good-bye parties were like wakes, because people saying goodbye did not expect to see each other ever again.

And so, on January 8, Lev Rubinstein started his day like any other. As he rushed somewhere on business and was hit by a car that did not stop at a crosswalk. He was hospitalized and put in an induced coma. A great number of people, online and offline, were following the situation and hoping for his recovery.

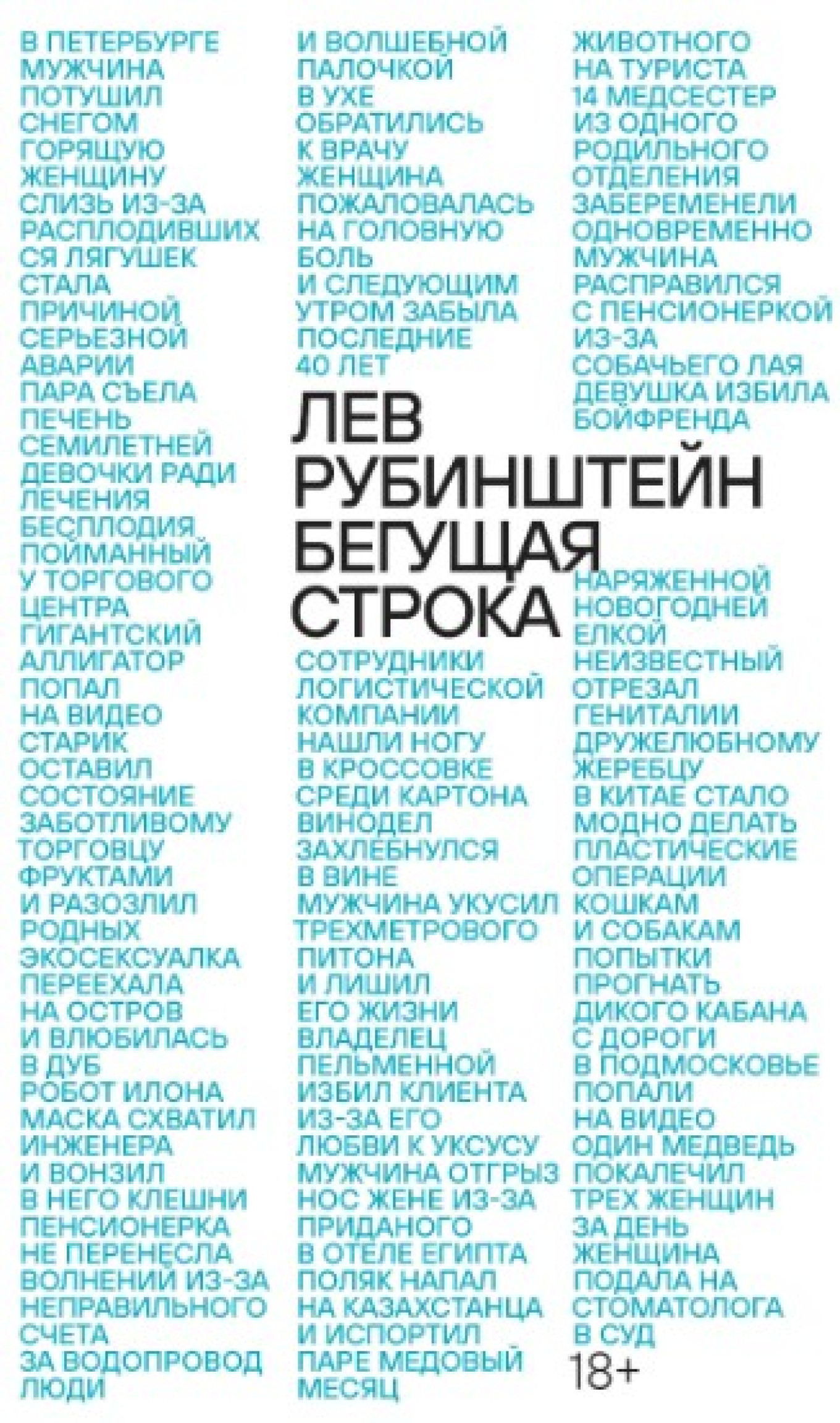

On January 11, his latest book, "Traveling Line,” a collection of ridiculous tabloid headlines, was sent to the press. Taken together they give an impression of a non-stop conveyor belt of absurdity rushing forward.

"Flying cockroaches forced a woman to quit her job."

"Doctors found a zucchini in the rectum of a Russian director."

"Biden bit a little girl and was caught on video."

"A Russian pensioner mistook a library for a military recruitment center and set it on fire."

On January 12, the news came that Rubinstein had died. Obituaries began to appear. Even those who did not know him personally wrote that now Moscow felt absolutely empty, as if the last hopes and optimistic illusions had gone with him.

Awkwardly, the information turned out to be false. Illusions returned for a while. The audience froze in anticipation of the next card.

Two days later, Rubinstein did die, and the Internet was flooded with a torrent of grief and love. The loss was bitter and disconcerting. There were even remarks that the poet had been killed by modern Russian reality, if not literally, then metaphysically. He might have died of an age-related illness, or he might have been arrested with the worst consequences. But life turned out to be as unpredictable as a conceptual text.

But the card catalog did not end there. Rubinstein reformatted the poetic space, freeing it from all kinds of boundaries. The poem cannot be interrupted and now writes itself. And so the title of the obituary article that appeared on the website of the newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets seemed to continue his last book: "Lev Rubinstein's prophecy has been spoken: "Mankind will learn to control gravity."

The fragmentary nature of card-poetry and its ability to accommodate all the chaos of speech has outpaced not only many contemporary genres, but also the social media age itself. Rubinstein's catalogs are now often referred to as a sort of Twitter, created long before the spread of the internet. The only difference is that from these analog tweets on thin cardboard with a round hole, the poet-bibliographer always stitched together some lyrical whole. The card catalogs begin as ironic, rationally detached lists of phrases, but each time they turn out to be breathtaking poetry.

For example, one of his most famous texts, "Mama Washed the Window" starts with the simple reproduction of a well-known phrase from a Soviet primer.

1.

Mama washed the window

2.

Papa bought a TV set

3.

The wind was blowing

4.

Zoya was stung by a wasp.

These are followed by dozens of similar stanzas, creating a kind of innocent school essay. The picture of one particular childhood emerges from familiar word combinations that were found in textbooks and copybooks, handwriting on desks and fences. In life, terrible events go side by side along with comical ones, and the signs of the postwar era appear.

55.

My brother said that Stalin died today.

56.

My brother hit me because I laughed and grimaced.

57.

Papa quit smoking.

58.

We hoped that war would break out sooner.

Then the materiality and physiological reality of the specific person is replaced by generalization: a multitude of characters appears, the words' meanings become symbolic.

68.

I once saw such a huge caterpillar that to this day I cannot forget it.

69.

I felt nauseous and vomited.

70.

Once, entering Galia Fomina's room without knocking, I saw for the first time.

71.

Once, obsessed by terrible premonitions, I rushed in.

72.

They got there, but quite late.

The tension grows, a thunderstorm with hail hits and the tops of fir trees tremble. When the disparate contents of the cards begin to rhyme, we are finally seized by the intense rhythm of nostalgia for a bygone childhood, the paradoxical combination of life that is absolutely tangible and utterly ephemeral.

But Rubinstein would not be Rubinstein if he ended the poem on such a high note. The storm abruptly subsides, the stanzas simplify again. The last two, as he himself explained, "contain a hint of some sort of beginning, indeed a clearly clichéd beginning, of some sort of narrative." That is, a Buddhist rebirth happens to us in the finale; it is not an ending but a beginning, though partly still an ending.

82.

That day was a day like any other.

83.

I got up, got dressed...

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.