On the edge of a park in a sleepy neighborhood in northern Moscow, a Russian Orthodox priest is giving an outdoor sermon to a small congregation huddled together in the November cold. Facing them on the opposite side of a flimsy wire fence, is an altogether angrier gathering of about 100 protesters. “Get out of our park,” they chant. “Out!”

The standoff between the group of believers and protesters has become a weekly Sunday fixture at Torfyanka Park. At stake is the proposed construction of an Orthodox church. The protesters say they are just defending their local park from an illegal land grab.The Orthodox Church has branded them “church and cross haters.”

More than a year and a half after the protest began, the conflict is no nearer to resolution. In fact, this month the fight seems to be escalating to new heights after protesters’ homes were raided by riot police. It was a lesson to grassroots protesters throughout Russia: When you take up an adversary as powerful as the Russian Orthodox Church, you should get ready for a long and difficult fight.

Morning Call

“It was around 6 a.m. when our doorbell rang over and over again, rrring, rrring, rrring!” says pensioner Alexandra Trofimovna, 68, gesturing emotionally. “We kept asking: who is it? There was no answer. Then they forced the door open with an angle grinder, and a group of officers stormed in.”

Trofimovna’s family was among roughly a dozen Torfyanka protesters who received unannounced visits from masked riot police on Nov. 14. During the raids, phones and computers were confiscated and searched. “They kept asking: where is the money? They think we’re being paid by the U.S. State Department or the British intelligence service,” she says.

Her daughter played an active role in the Torfyanka protest and law enforcement now consider her “an instigator,” Trofimovna says. “But there is no organizer. People come themselves, they want their park.”

The protesters have been called as “witnesses” in a criminal case on

charges of “insulting the feelings of religious believers,” in which as

of yet no one has been charged. According to media reports, prosecutors

opened the case after receiving complaints from various religious

figures and Orthodox activists, who claim the Torfyanka protesters are

violating their religious rights.

When asked about that

accusation, a middle-aged woman at Torfyanka reacts with a mix of

offense and incredulity, befitting of a country where about 70 percent

of people identify as Russian Orthodox. “We are all believers here!” she

says.

200 Churches

The protest over Torfyanka

stretches back to early summer 2015, when construction of a new Orthodox

Church began on the edge of the park.

The future place of worship was part of the “200 churches” program,

launched in 2010 by former mayor Yury Luzhkov and Patriarch Kirill.

The

plan was as simple as it was ambitious: to bring Moscow closer to the

national average of one Orthodox church per 11,000 people. Upon

completion, Luzkhov said, Moscow would be a city where there would “not

be a place without God's church within walking distance.”

Many

Muscovites, however, have not welcomed the Church's expansion boom,

especially when it comes at the expense of local parks and squares. In

many cases, residents have been presented with a fait accompli.

“They started building in the middle of the night, like thieves,” says

Viktoria Mironova, a Torfyanka local. “It came as a complete shock.”

Over the past years, various local protest movements have sprung up

around the capital — some pushing for new locations, others questioning

the need for more Orthodox churches in a multi-faith city.

At

least 27 planned churches have been forced to find a new location after

meeting a wall of local resistance, according to the Vedomosti business

daily.

After several months of confrontation at Torfyanka, the Church announced

in August last year that it was willing to move. It had reason to

compromise. Clashes between local residents and ultra-orthodox activists

of the “40x40” movement — a vigilante group whose name refers to the

supposed 1,600 churches that existed in pre-revolution Moscow — had

resulted in various broken bones and much negative publicity.

Under

public pressure, prosecutors had also started a probe into the legality

of the construction plans.

After a majority of residents backed relocation in an online vote on the

authorities’ Aktivny Grazhdanin platform, the church was offered a

different plot nearby. In April, a new church opened its doors two

kilometers away — but conflict never left Torfyanka.

Information War

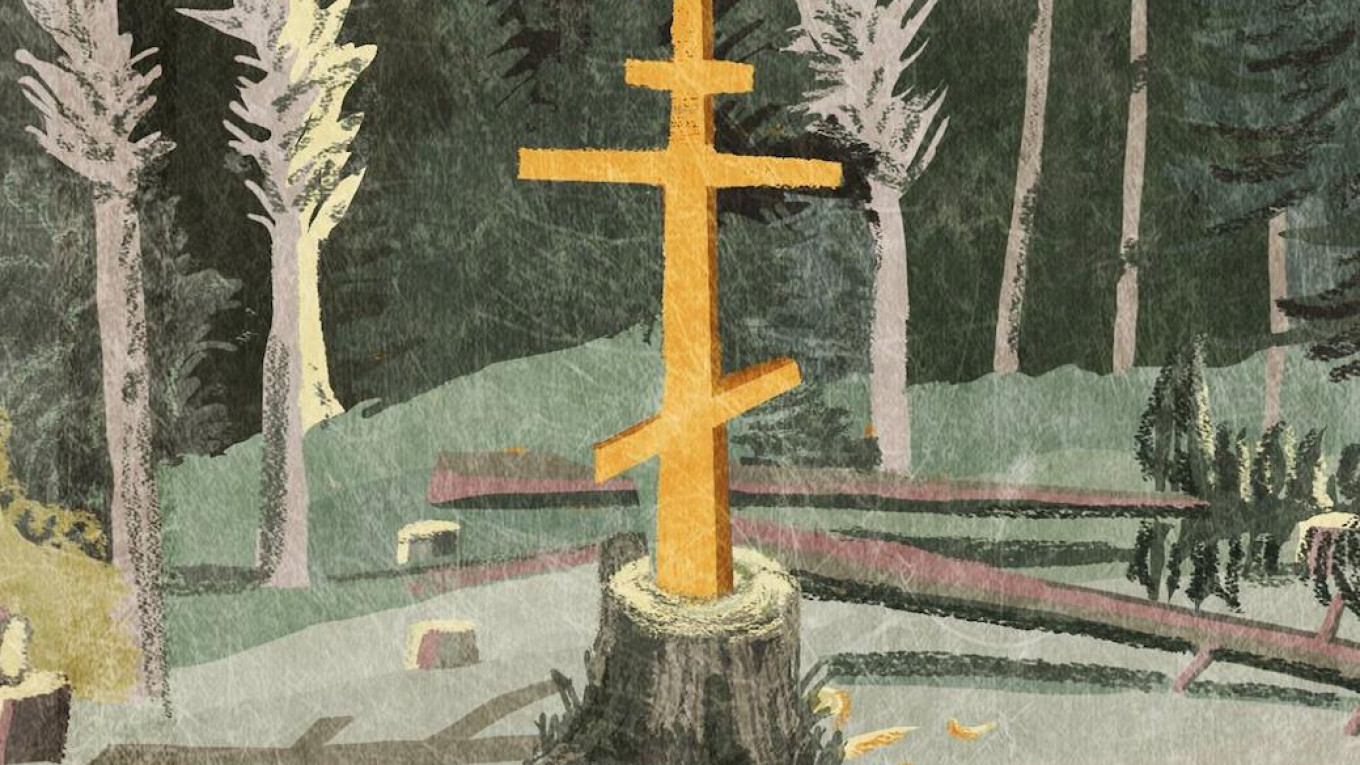

At

the center of current tensions is a two-meter-high Orthodox

cross left behind in the park on a plot surrounded by a wire fence.

Here, a small congregation of activists continues to hold a weekly

service. In the eyes of the residents, it is a deliberate provocation and presents a continuous threat that construction will resume once the protesters let down their guard.

“Why can’t they just leave the park?” asks Mironova, adding that she, an

Orthodox believer, was refused admission to the service for being a

“church hater.”

Such demonizing language has become more widespread, especially from state media, protesters complain. A camera crew belonging to the Kremlin-sympathetic NTV television station filmed the early morning raids by law enforcement — much to the residents’ surprise and annoyance — and aired the segment under the heading: “Raids on neo-pagans.” The pro-Kremlin Life.ru tabloid has also recently run stories branding the protesters as “extremists.”

Some residents blame the wave of negative coverage on Patriarch Kirill,

whose public statement last month put an end to their hopes of peaceful

reconciliation.

“Today, the cross is being fought with the same fury as the construction

of the church. Maybe it wasn’t about the defense of the park from the

start, but a battle against the cross, a symbol of Christianity?” he

said at a religious forum. “We can’t take our cue from people who have

an ideological hatred of the Lord’s cross.”

He also dismissed

the Torfyanka movement as consisting of “representatives of sects and

pagan communities” and opposition politicians.

As the Torfyanka protest has grown, it has inevitably become a rallying point for

those who oppose the growing influence of the Orthodox Church on

society, such as the introduction of a 2013 law criminalizing “offending

the feelings of believers.”

“The authorities could solve

this problem in ten minutes if they wanted to,” the leader of the Moscow

branch of the opposition Yabloko party, Sergei Mitrokhin, said at the

Sunday protest. “But in today’s Russia, the Patriarch calls the shots

and authorities fear him.”

Though many of the protesters

welcome any support they can get, they are keen to emphasize the initial

apolitical nature of the conflict. “This started as a peaceful,

civilian protest, it’s a conflict over urban planning,” says Mironova.

“Many of us are believers, too, but we’re being branded traitors!”

Analyst Yekaterina Schulmann says the religious rhetoric acts as a

smokescreen for the vested financial interests of developers’ plans to

exploit valuable Moscow land.

“This is not so much about the church as about the Moscow developers

industry,” she says. “The church is in it, too, of course, but mostly

for PR-support: Haters of the Cross sounds better than enemies of

developers.”

No End

Without mediation, however,

the conflict at Torfyanka looks set to escalate. At the most recent

Sunday service, a busload of police officers was forced to intervene as

angry protesters tried to stop a priest from driving away from the

scene.

“It only needs a spark to set off this barrel of gunpowder,” a Torfyanka

activist warned earlier this month at an urban forum in the capital.

“The two sides are prepared to kill each other.”

Such local

anger is unlikely to faze the religious activists, however. They see the protest

as an attack on religion itself and categorically deny there are

believers and local residents among the protesters.

“No believer would ever resist a church or a cross,” says 40x40 member Yury Shubin. “In the past, Russian Orthodox believers have been thrown to the lions, Christians have been burned alive and yet we did not deny our faith,“ he adds. “If the Patriarch wants a cross at Torfyanka, we will defend it to the end. Even if they start tearing us to pieces.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.