"People who get drunk on ordinary days do it out of love for the art of drinking. But on Tatyana’s Day they get drunk out out of a sense of duty — to prove their solidarity with the drinking intelligentsia. Even if life has taken us in different directions, the ties that bind us in the name of our foster mother — our alma mater — are still alive and intact in our hearts."

The author of this tribute to Tatyana's Day is Alexander Amfiteatrov (1862-1938), a Russian publicist and satirist. He was imprisoned and exiled under every regime. Under the Tsar — for satirizing the royal family. Under the Provisional Government — for criticizing one of the ministers. Under the Bolsheviks — for, well, just about everything.

He was able to relax only in 1921 when he escaped with his family by boat from Petrograd to Finland. But even there he couldn’t stay for long. He lived in Prague and Italy and wrote for Russian émigré newspapers.

"Tatyana" is a slightly nostalgic story from his collection of 1904. January 25 marks a feast day dedicated to the early Christian martyr Tatyana, but it was a decidedly secular holiday in Russian history. On this day, January 12 (January 25 New Style) in 1755, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna approved the project to establish Moscow University. Its patron and long-time curator Ivan Shuvalov may have chosen the date to petition the Empress on purpose, since it was the name day of his mother Tatyana. And with that, a holiday was created, first famous — or infamous — among students in Moscow and then among students all across Russia.

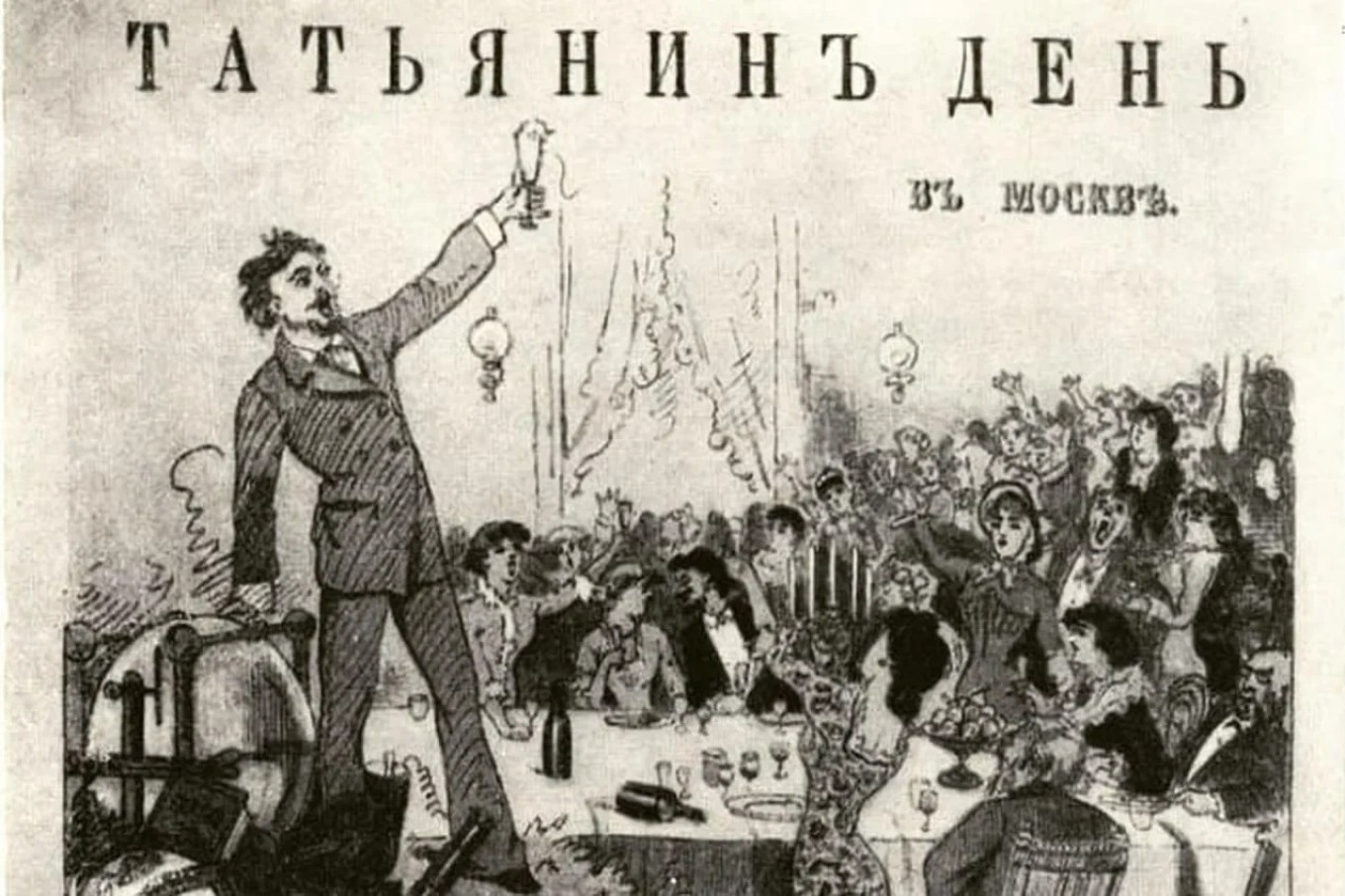

Tatyana's Day in the Russian Empire was always a raucous holiday. At the end of the 19th century university students celebrated it in the best restaurants — in the Hermitage, Strelna and Yar. At first this holiday was only celebrated in Moscow, but almost the whole city joined in.

Pyotr Ivanov (1875-1956) describes the holiday vividly. A 1901 graduate of the Faculty of History and Philology of Moscow University, in 1903 he published a book called "Students in Moscow. Life. Mores. Types."

"The motto of Tatyana’s Day was insane fun with no boundaries,” Ivanov wrote. “Forget your everyday life of petty cares. Become intoxicated, and have fun, have fun, have fun… The entire university and all the students are swept up in a mad whirl of celebration.

“The day begins solemnly. There is a scholarly speech. Students begin to whisper. Medals are awarded. A trumpet fanfare. The hall shows signs of life. The national anthem. Hesitant shouts of hurrah... Inhibitions are gone. The start of intoxication.

“’Gaudeamus’ is played one, two, three...”

“Then the action moved to inns, beer halls and middle-class restaurants. Now it all comes down to one thing: preparing a ground for the holiday of uninhibited abandon. No one had the money to get drunk on bottles of upper-class champagne. Intoxicating vodka and cloudy beer were the drinks of Tatyana's Day."

Moscow satirist Vlas Doroshevich (1865-1922) wrote that on this day Ivan Natruskin, the owner of a restaurant empire, turned away people who tossed hundreds of rubles at him. Instead he opened his fabulous winter garden completely to students who drank only beer. “But you have palm trees! God knows how much money they cost!” the people he turned away told him. The old man smiled. “So what?! They'll be doctors and lawyers, and then they'll pay!”

Another famous restaurateur, Lucien Olivier, would choose a poorly dressed young man on the street, give him money and say, “Please go to my restaurant, ask for a bottle of beer, pay two hrivnias and tip the man five kopeks.”

In the restaurant, diners were spending fortunes on their meals. Olivier would hide and watch how the spoiled waiter responded the five-kopek tip for tea. Would he bow to the diner the same way he’d bow to someone who tossed down a 25-ruble tip? Woe to the waiter who contemptuously pushed back the small tip or didn’t even look at the poor student.

Ah, how right Alexander Amfiteatrov was! “If anyone gets drunk to the point of falling down on all fours and crawling, let he not be embarrassed in his heart! It is better to crawl on all fours along the path of progress toward shining goals with a pure heart and lofty ideals than to walk on two legs to the police station and denounce a comrade."

What did the celebrating students eat? The most inexpensive dishes: giblets, sauerkraut, herring, boiled and jellied meat. They washed it down with beer, and had black bread, kvass or homemade fruit drink on the table.

We offer you one of the inexpensive but very appetizing dishes of student life. Prepare it, serve it, and remember your student days!

Kidneys in Madeira

Ingredients

- 6 whole veal kidneys

- 150 ml (2/3 c) of Madeira

- 50 g (3 ½ Tbsp) butter

- 18-20 small mushrooms

- 200 ml (5/6 c) broth

- 1 shallot

- salt, freshly ground pepper to taste

Serve with butter-fried white bread croutons

Instructions

- Rinse, salt and pepper the skinned kidneys.

- Sauté in heated butter (you can add a little vegetable oil to prevent burning). Place them in a colander or on a paper towel to soak up excess oil.

- Boil the mushrooms.

- Put chopped onions in a skillet, sauté lightly, then add the mushrooms.

- Pour in the Madeira, boil for a few seconds, then add the broth. (If there is no broth, you can add water).

- Add the fried kidneys to the sauce and cook for 2-3 minutes over low heat without bringing to a rolling boil.

- Add butter and stir.

- Serve the kidneys on a warmed dish. Pour over the sauce and garnish with slices of white bread fried in butter and sprinkled with chopped parsley.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.