Cabbage soup, blini and pirogi are the symbols of Russian cuisine. But there is another contender for this title that might come as a surprise to foreigners: quinoa. For many centuries bread made with a local variety of quinoa called orache (лебеда) offered salvation from hunger. It was also simply a very common food product.

Today in Russia there is a nationwide nostalgia for Soviet bread. The world's best bread and ice cream are the symbols of the bygone "Soviet happiness" that our fellow citizens speak about with such longing — especially our fellow citizens born in the 1990s.

This is all fine and good except for one small problem: it contradicts the population's no less nostalgic longing for ye olde Rus, for the Tsar with his loving, fatherly care for his people and their sustenance. If we remember that era in terms of bread and baked goods, we immediately think of bread made with the grain quinoa. Some say that is a Bolshevik myth to slander those blessed times; others say that no one in the world had better food than the Russian peasant. But we say: let’s look back on quinoa in Russian cooking calmly and objectively.

Why isn't it a national dish? Of course, quinoa was not only eaten in Russia, just as, say, turnips don’t only grow in Russia. But if we change our gaze and look to the past for food products that weren’t just a way to stave off hunger from poverty and crop failure, but a way to rationally use the food available, we might find something positive.

Today hardly anyone has tasted quinoa bread. But it has been helping Russians keep hunger at bay for centuries. White quinoa seeds were indeed often used during the famine years to bake a kind of surrogate bread. This made sense. Quinoa contains fats, a lot of nitrogenous substances (proteins), starch and fiber. However, the bread was bitter, crumbly, difficult to digest and caused severe irritation of the digestive tract.

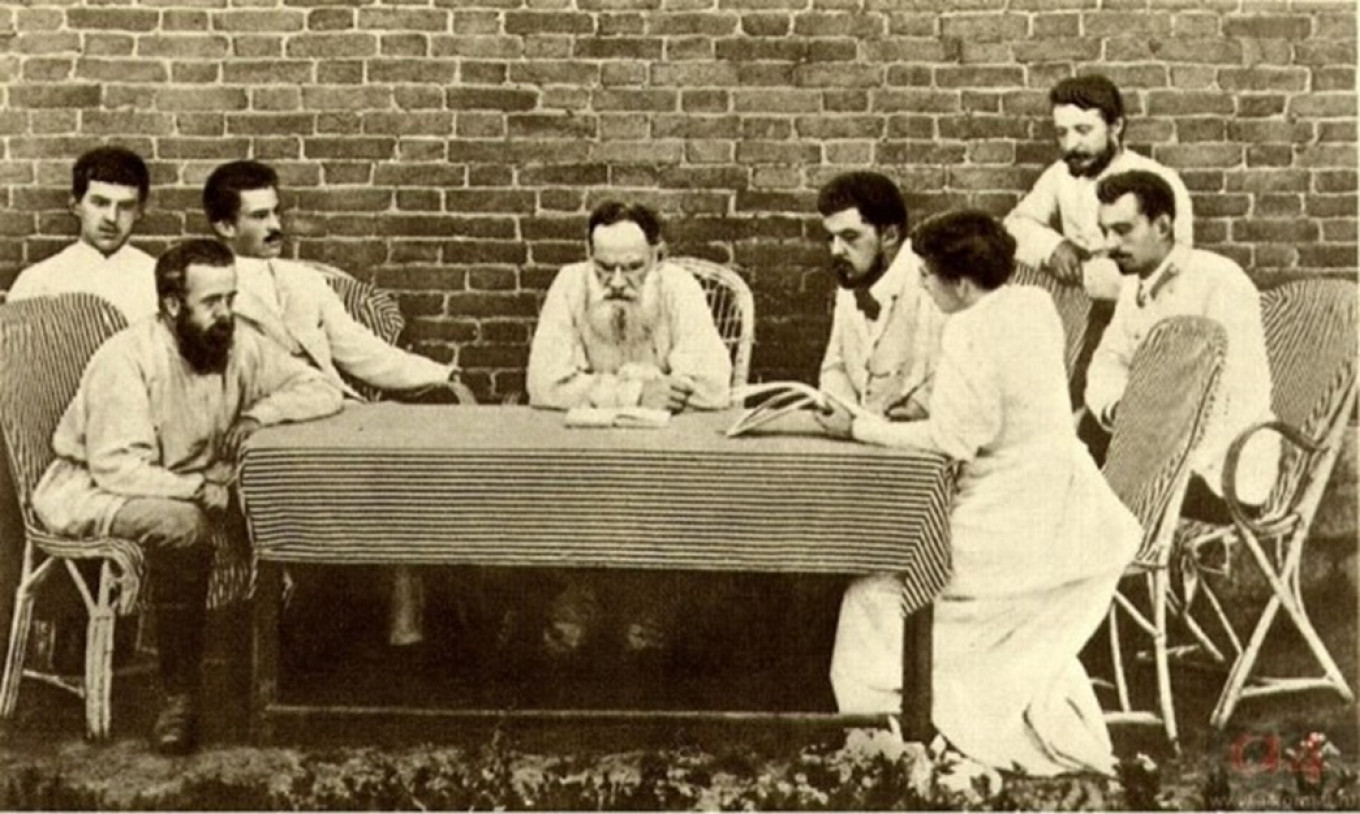

"On the border of the Yefremovsky and Bogoroditsky counties,” Leo Tolstoy wrote about the famine of the 1890s, “the situation is dire. Almost everyone eats bread made from quinoa, but the quinoa here is green — that is, unripe. There is no white kernel at all, and so it is inedible. Bread with quinoa should not be eaten alone. If you eat just that bread on an empty stomach, you will vomit. People get sick from kvass made from quinoa flour.”

The topic was clearly in the focus of public attention. It turned out that the chemical composition of bread made from quinoa kernels is relatively close to that of rye bread. But experiments that were conducted on the digestibility of bread made from quinoa during the crop failure of 1891-1892 yielded poor results.

Many scientists noted that quinoa kernels were poisonous. In his letter to the editor of "Russian Vedomosti" Professor Fyodor Erisman wrote strongly against bread made with quinoa: "It is highly undesirable for peasant to replace rye with quinoa during crop failures.”

We found a note from the magazine "Our Food" (1893) says that "in all the scientific experiments to feed people quinoa, we observed weight loss and poor health. Bread made of quinoa is disgusting and cannot be eaten in large quantities. It is difficult to peel off the quinoa husks, so bread is baked with the whole kernels.”

So what does this have to do with everyday cuisine? Quinoa bread is solely a symbol of hunger and calamity, a food our ancestors ate to stay alive in hard times.

But, as usual, things are not so black and white. In the Russian village quinoa was not just a remedy for hunger but food commonly eaten in a thrifty household. This was, of course, something that Leo Tolstoy noticed.

"In the courtyard of the house where they showed me quinoa bread I saw there was a threshing machine powered by four horses; oats from their own and rented land; and 60 stacks of oats worth 300 rubles. It is true that there was not much rye left — about 800 kilograms — but, besides oats there were up to 4000 kilos of potatoes and buckwheat. And the whole family of 12 souls ate quinoa bread.”

In this case eating bread made of quinoa wasn’t a sign of calamity but a way for a thrifty homeowner to eat less bread. For the same reason an economical peasant never gave his family warm or soft bread in years of plenty — only dried bread. “Flour is expensive, and one can't get enough of it! People eat quinoa bread, so what kind of gentlemen are we?” one thrifty farmer told Tolstoy.

Besides, for all the disadvantages of quinoa, there is one key advantage: It is always at hand. In Russian life over the centuries, that is always welcome. Calamities come and go, and in each era the salvation is different. Once it was quinoa, and once it was “Bush legs” — chicken sent by the U.S. as food aid in the early 1990s.

So don’t rush to condemn quinoa. Today a variety of quinoa is very popular among people who maintain a healthful diet. Life plays curious tricks on us, even in the kitchen.

Quinoa with Zucchini and Onions

For 4 servings:

Ingredients

- 600 g (1 1/3 lb) young squash or zucchini

- 2 Tbsp olive oil

- 1 Tbsp butter

- 2 medium onions

- 3 garlic cloves

- 2 sprigs of thyme

- 200 g (7 oz or 1 1/8 c) quinoa (a mixture of white, red and black quinoa)

- 1 small bunch of parsley

- juice of 1/2 lemon

- 2 Tbsp pine nuts

- salt, freshly ground black pepper

Instructions

- Prepare quinoa: rinse the grains several times in cold water.

- Pour 1.5-2 liters/quarts of cold water into a saucepan, add a pinch of salt and the quinoa. Bring to a boil.

- Turn down the heat and simmer over low heat for 15 minutes.

- Drain through a sieve and leave in the sieve for a while to allow the steam to escape.

- Cut the zucchini into very thin (5mm[1/8 inch]) slices.

- Slice the onion into thin half rings.

- Finely chop the garlic.

- Coarsely chop the parsley leaves.

- In a skillet over medium heat, melt butter and olive oil. Note: The skillet should be large enough to fry the vegetables, not stew them.

- Add zucchini, onion, thyme, salt and pepper to the skillet and cook over medium heat 15-20 minutes until the zucchini is soft and golden.

- Add garlic and cook for another 1-2 minutes.

- Combine quinoa, zucchini and onion and mix well.

- Drizzle with lemon juice, add parsley, salt and pepper to taste.

- Serve with toasted pine nuts.

*Zucchini can be replaced with sliced pumpkin and onions with leeks.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.