Was television presenter Anastasia Ivleeva’s party at the Mutabor Club tawdry and in poor taste? Perhaps. Was its “almost naked” theme intended to be scandalous? Most certainly.

Yet it was a private event for the type of entertainers we imagine attend risqué parties now and then. Everyone from the courts to conservative Russian politicians and the Orthodox Church has attached their collective outrage to the idea that this is not how to behave during a time of war.

However, the so-called “special military operation” has not prevented football matches or theater performances, pop music concerts, or even a major event like VK Fest 2023 from going ahead. The claim that Russian youth are not dying to support such lurid hedonism also falls flat since the Kremlin has long assured citizens that military operations in Ukraine will have little impact on daily life far from the front line.

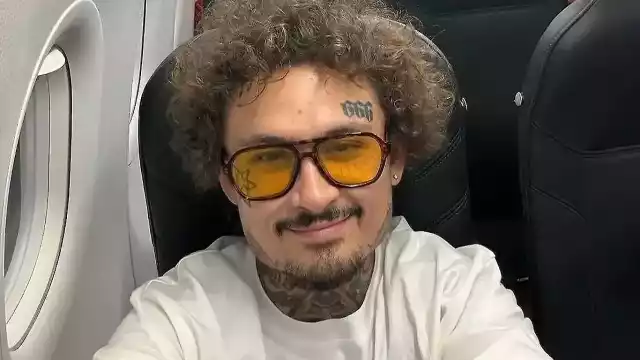

The strictest legal consequences of the party have fallen on rapper Nikolay Vasilyev, who goes by the stage name Vacío. In keeping with the party’s theme, he attended wearing only his sneakers and a sock covering his genitals. For his daring outfit, a Moscow court found him guilty of disrupting public order, using vulgar language, and promoting “non-traditional sexual relationships” in Telegram channels. He has been sentenced to 15 days in jail and fined 200,000 rubles ($2,210).

Having long-followed the Russian hip-hop scene, I believe these charges, let alone Vacío’s conviction, are an alarming development. While authorities have criticized some rap music before, plenty containing vulgar language and references to sex and drugs, such as the song “Hello Kitty” by teenage rapper Ugly Stephan, go unchallenged. There are plenty of music videos, like GONE.Fludd’s “Traxxxmania,” that show women wearing just as little clothing as the ones at Ivleeva's party. They received no official rebuke.

As for the video of the party that was shared on Telegram, you can find lots of photos of nearly naked young women on many VKontakte accounts. The authorities do nothing about that. Rappers Pharaoh and Lil Morty have both had images of violent thugs armed with guns in music videos, while other rappers extoll the virtues of drugs and drug dealing. It is rare that any of this garners official, much less legal, ire.

While Vacío’s criminal conviction is officially for “petty hooliganism,” the complaint cites “propagating non-traditional sexual relationships.” Similar complaints were made against Ivleeva and other attendees. It is peculiar to insist that these celebrities are violating laws against spreading “LGBTQ propaganda” since anyone who has seen a music video or listened to a song by Vacío would know he likes the ladies, to say the least.

The rapper himself made a public apology for his participation in the party and asserted he does “not support LGBTQ.” The public apology itself is troubling, as an artist who could use their platform to speak out against injustice is instead parroting the official narrative about the party, despite at first being defiant regarding his participation in it.

More troubling though is that the prosecutors brought “propagating non-traditional sexual relationships” into the equation in the first place. This is especially telling given the prosecution of a male for his near-nudity. Such is fine for female models on VK, apparently. But if a man dares to strip down the obvious conclusion appears to be he is gay or promoting homosexuality.

The resulting message that women can be objectified, but nearly naked men are not straight, reveals a lot about the real motivation behind much of Russia’s current anti-gay measures. As part of a conservative trend ahead of the presidential election, the Russian Supreme Court recently banned the so-called “international LGBT movement” as an extremist organization, with lengthy prison sentences for people violating the law.

The interpolation with anti-gay legislation could be the result of authorities simply grasping for something in the criminal code to punish the attendees. However, they might also have seen an opportunity to underscore what the Orthodox Church and some arch-conservatives desire: a god-fearing state where only the nuclear family is accepted. Scantily-clad women in music videos are tolerated because they in theory encourage young men to pine for a beautiful girl and one day, a wife. Vacío running around a nightclub naked, however, clearly crossed a line: a man should not be seen that way.

Though Vacío’s outfit would be wholly inappropriate for a walk down a public street, covering oneself with just a sock is sufficiently tame to have been used in a 2014 testicular cancer awareness trend on Instagram. As for many of the other party-goers’ outfits, most were no more explicit than underwear adverts in fashion magazines. From viewing videos of the event and speaking with several attendees who wish to remain anonymous, it seems to me that despite the scandalous theme, it was a very heterosexual affair altogether.

Russia’s current constitution broadly provides citizens with the right to a private life, free expression, freedom from censorship, and freedom of assembly. The right to host a private party — regardless of its poor taste — seems reasonably assured. The right to distribute a video that does not really cross the line into pornography on Telegram channels not intended for minors should, in theory, be protected under freedom from censorship.

The specific charges brought against Vacío are telling in their obscurity and a stretch for legal authority. For anyone who follows Russian hip-hop, the double standard is all too apparent: very lurid content — content that even I as a fan of Russian rap often find myself turning off — is permissible, but it must always somehow echo conservative mores, even if it does so quite perversely.

Ivleeva’s “nearly naked” party presented a conundrum the authorities feared because it departed from the tropes about what Russian life should entail, which both the Kremlin and Orthodox Church cling to. It is a shame because much of what made Russia great in post-Soviet times was its diversity and complexity of ideas that are now being crushed.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.