The retrospective show "Gabrielle Chanel—Fashion Manifesto" at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London takes visitors on a journey that begins with the iconic designer’s first millinery boutique in Paris in 1910 and ends with her final collection in 1971. Featuring over 200 looks brought together in one place for the first time, the show shines a spotlight on both little-known pieces held by the Museum and showstoppers from the fashion house, Patrimoine de Chanel, and the Palais Galliera (Paris Fashion Museum).

The show and recent books on the designer also crack open a door to what few know about Chanel: her fixation with Russian aesthetics in the early 1920s, inspired by or part of her fascination with the Russian émigrés in her social circle. “This interest manifested in her designs of the period,” says Oriole Cullen, the curator behind the show "Gabrielle Chanel—Fashion Manifesto." “Chanel employed several Russian émigrés at her salon. These influences in her professional and personal lives have led some biographers and fashion historians to refer to the early 1920s as Chanel’s ‘Slavic period’.”

Although Chanel never set foot in Russia, the London show gives many examples of traditional Russian patterns, decoration and embroidery in her clothes. The designer loved Russian culture and Russian men, as she confessed to her friend Paul Morand, author of “L’Allure de Chanel,” a biography based on conversations held in a hotel in St. Moritz, Switzerland, in 1946.

“I think all women from the West should capitulate to the ‘Slavic charm’ to know what it is,” she told him. “I was fascinated by the Russians... All Slavs are distinguished; the most humble among them are never banal.”

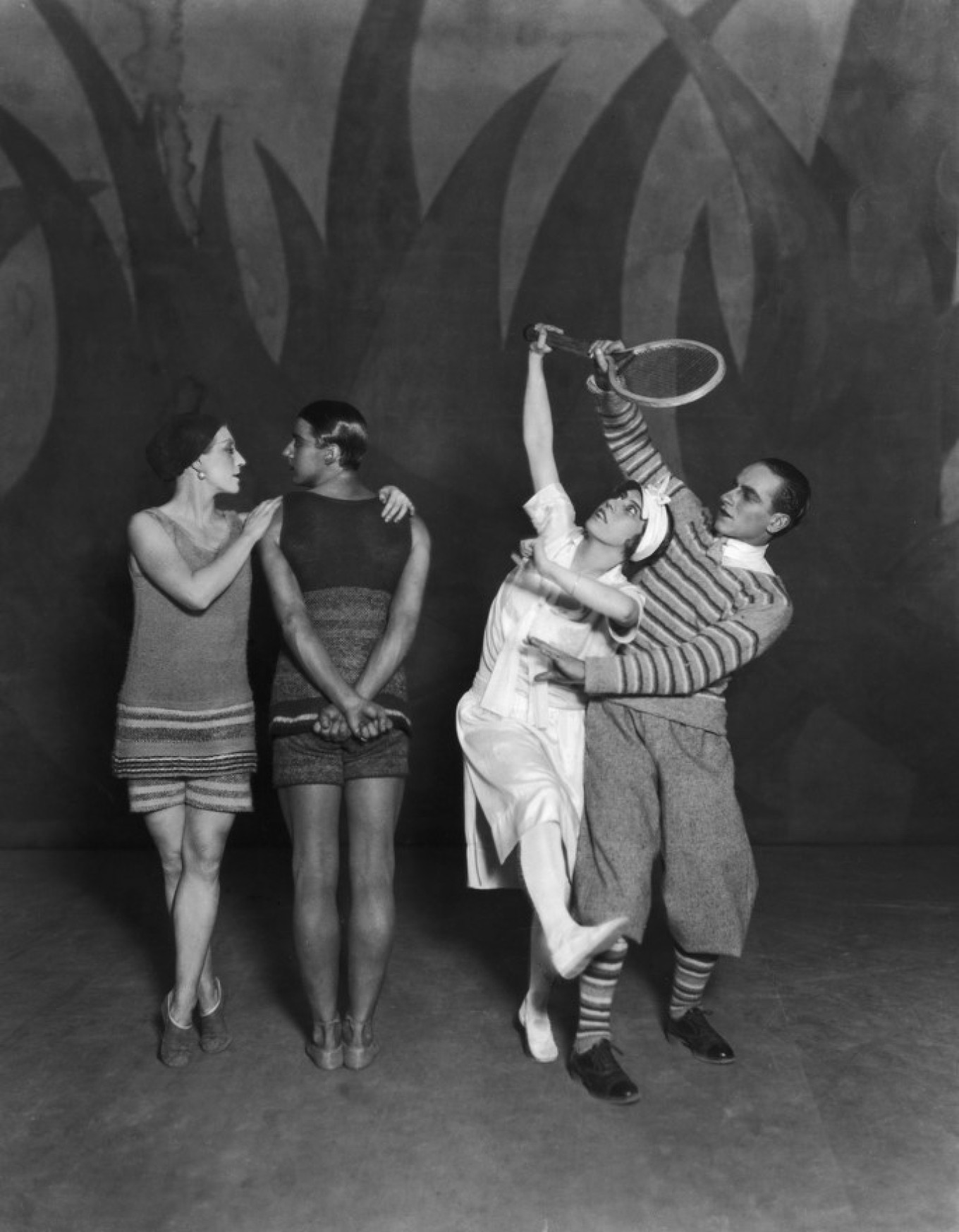

Chanel’s close friendship with Sergei Diaghilev, the visionary producer of the Ballets Russes — the most innovative dance company of the 20th century — lasted until he died in Venice in 1929. She designed the costumes for many of his productions including “Le Train Bleu,” a stylish one-act ballet set on the French Riviera choreographed by a Russian dancer of Polish origin, Bronislava Nijinska, with a libretto by Jean Cocteau.

In 1913, Diaghilev took her to the premiere of the still shocking “The Rite of Spring” at the Théâtre de Champs-Elysées in Paris. The Stravinsky masterpiece was greeted with boos, jeers and hisses while Coco Chanel sat “mesmerized,” as described by English poet Chris Greenhalgh.

It took seven years before Chanel and Stravinsky met in person. They were introduced by Misia Sert, née Godebska, a Russian-born pianist and patron of the arts during the Belle Époque. As the English poet Chris Greenhalgh recounts in his book “Coco and Igor,” Chanel invited Stravinsky to work in her country villa in Garches, outside Paris. The composer agreed to move in with his consumptive wife, Katherine Nosenko and their four children. The composer’s official biographers confirmed the passionate summer affair between Chanel and Stravinsky.

However, it burned out quickly when she met an attractive Russian aristocrat in Biarritz. This was Dmitry Pavlovich, Grand Duke of Russia, first cousin of Tsar Nicholas II, who was described by one American reporters as a sort of Rudolph Valentino. Slender, clean-shaven, and well-groomed, he was renowned — or notorious — for taking part in the December 1916 assassination of Grigory Rasputin, organized by Prince Felix Yusupov. For his part in the murder, Nicholas II exiled the Duke to the Persian front. Escaping the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Duke then emigrated to Western Europe. Like many other fleeing Russians, he ended up in Paris in 1920.

“Chanel recounted to Paul Morand that she was captivated by Pavlovich and his circle,” Cullen said, “but at the time she was still romantically involved with composer Igor Stravinsky. In 1921, however, she had begun a romantic relationship with Pavlovich that lasted one year.” The new couple soon had an off-season stay in Montecarlo, where they tried to live as discreetly as possible. Chanel was 11 years his senior.

Russia-inspired embroideries

The curator of the London show told The Moscow Times that some of Chanel’s most intricate embroideries of the early 1920s on display were carried out by the House of Kitmir, established in 1922 by the Russian Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna Romanova, who had fled Russia after the Revolution of 1917. She was introduced to Chanel by her brother, Dmitry Pavlovich.

In her book “A Princess in Exile,” published in 1932, Maria Pavlovna described the beginning of her collaboration with Chanel. “In the autumn of 1921, I met Mademoiselle Chanel, the most successful dressmaker in Paris since the war and a promising businesswoman,” Maria Pavlovna wrote. “This unusual woman crossed my path at precisely the right time. ... Less than three months later, I brought her a blouse embroidered on a machine.”

“The collaboration between Chanel and the Grand Duchess is unique in the history of fashion for the duration and intensity, and the complexity of the patterns,” said Nadia Albertini, a Franco-Mexican embroidery and textile designer and fashion historian based in Paris who is the lead author “Kitmir: les broderies russes de Mademoiselle Chanel” just published by Gourcuff Graden. “The use of Cornely machine to translate the traditional Russian peasant embroideries results in beautiful and super intricate chain stitch embroideries,” Albertini said. “For the first time in a book, we show 20 detailed pieces belonging to a larger collection…a real treasure.” Albertini also said that “the samples Maria Pavlovna created for Chanel have been preserved for more than 100 years by Maison Hurel, the oldest embroidery house in France, which bought Maria Pavlovna’s company in 1929.”

Chanel worked with the House of Kitmir by Maria Pavlovna on several collections consisting of tunics, pelisses and rubashkas. Albertini says that one of those tunics, found in a French château and part of the Chanel 1922 Spring/Summer collection, was sold for 130,000 euros at auction last November.

Beaux's Eau de Russie

During a romantic stay in Grasse, where the perfume industry began, Dmitri introduced Chanel to Ernest Beaux, a Russian-born French perfumer who had created scents for the imperial court, including Bouquet de Catherine, a fragrance produced in 1913 for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. “Beaux was the former technical director of Rallet, the leading perfume and soap manufacturer in Russia, which supplied the Russian imperial court until the Revolution in 1917,” Cullen said.

Coco wanted him to create her signature perfume. “Beaux submitted to her different sample scents identified only by number. Coco chose the sample N° 5, a fragrance with a rich aroma containing more than 80 ingredients,” Cullen said.

Chanel and Dmitry Pavlovich maintained a strong friendship throughout her lifetime. The woman who was born illegitimate into poverty had a career that spanned six decades, only ending with her death at age 87 in 1971. Her “Russian period” had ended long before and was almost forgotten. But the French designer never forgot and never regretted her connection with Russia. Coco would later comment while sitting down at her couture salon at 31 rue Cambon in Paris: “These grand dukes…an admirable face behind which there is nothing, green eyes, broad shoulders, fine hands and the most peaceful people, shyness itself. They drink just not to be afraid. Tall, handsome, and superb, these Russians are.”

The exhibition “Gabrielle Chanel. Fashion Manifesto” will be at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London through February 25, 2024. For more information, see the site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.