“You can't carry your homeland with you on the soles of your boots," French revolutionary Georges Danton told friends when they suggested he flee France shortly before his arrest. You may not be able to take your homeland with you, but you can take your cuisine. We saw this time and again in the 20th and 21st century waves of Russian emigration.

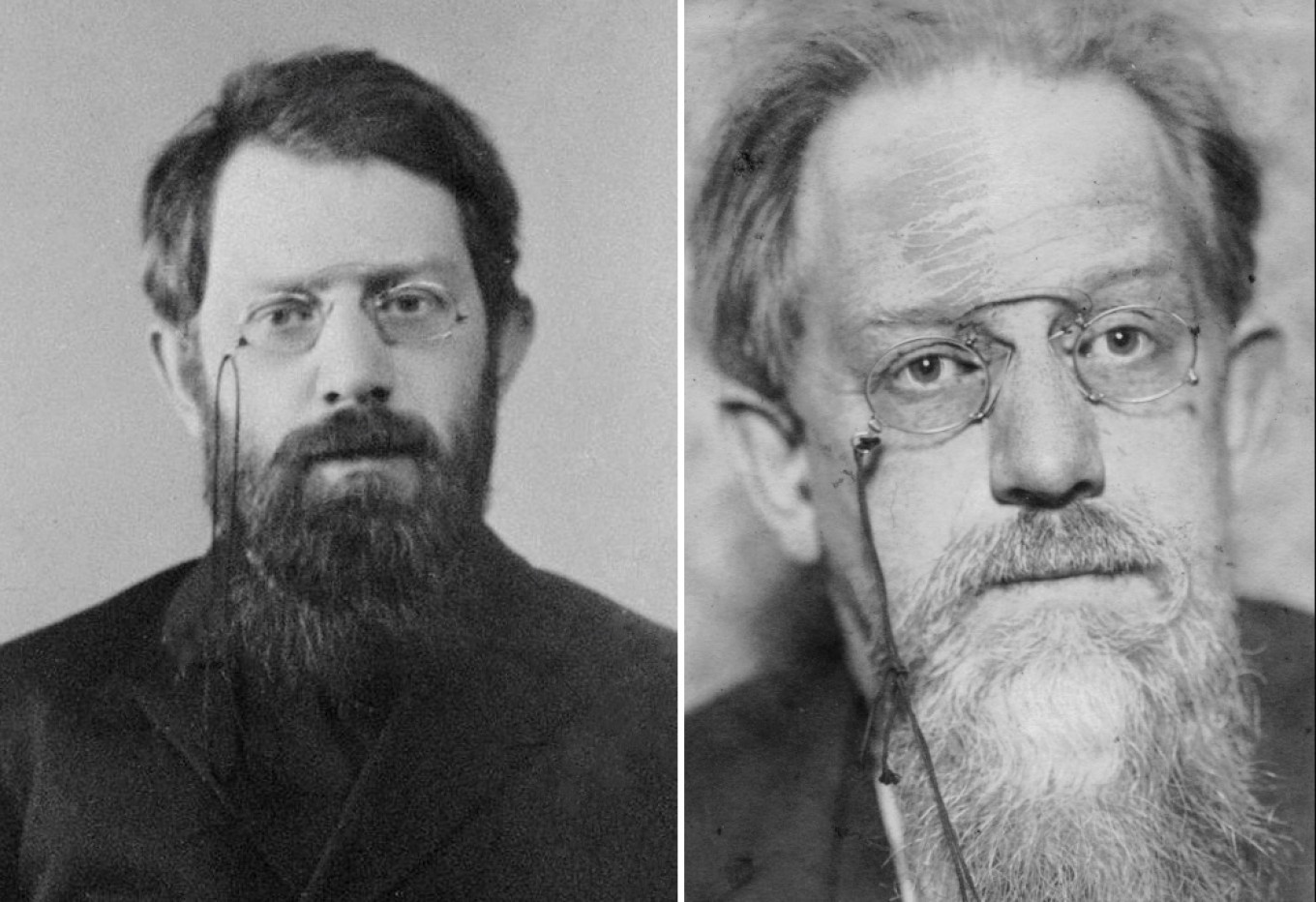

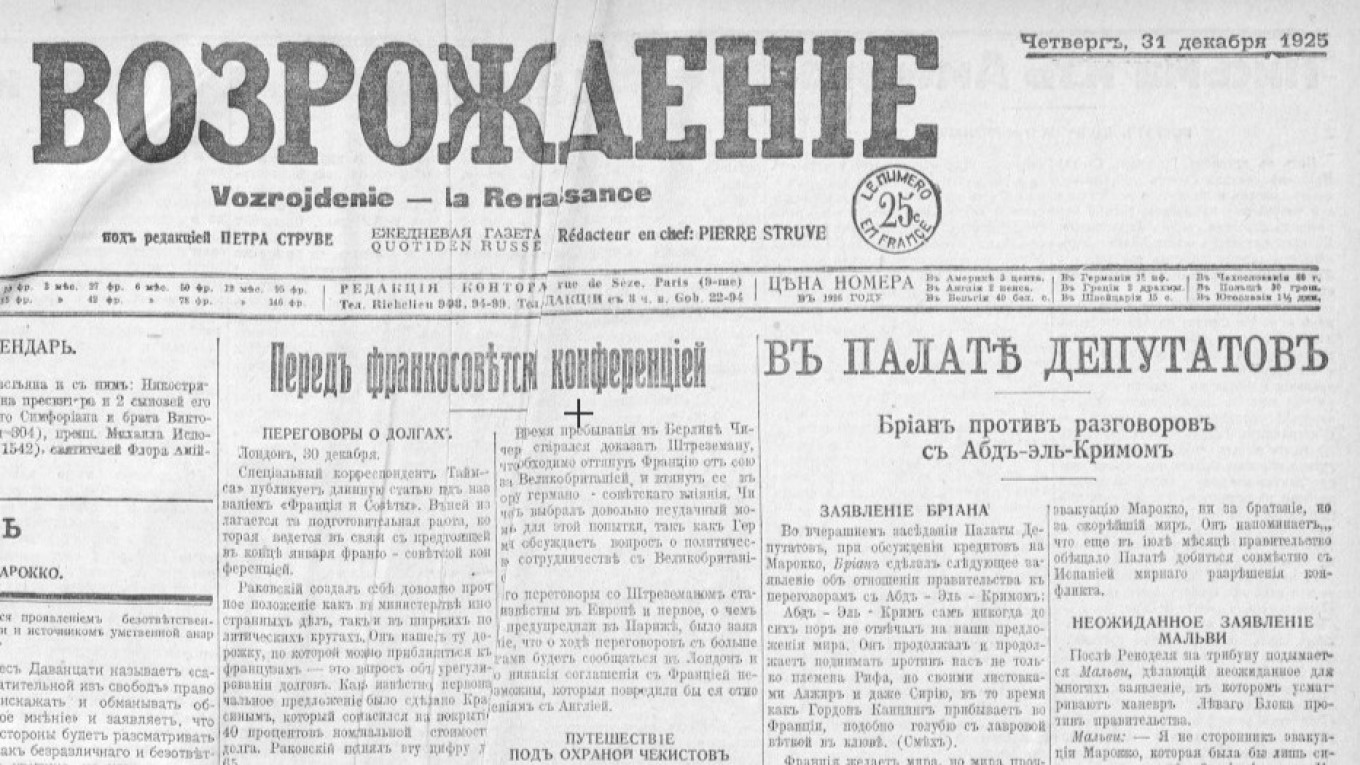

The emigrant newspaper Vozrozhdenie (Rebirth) was published in the French capital from 1925 to 1940. Its editor, Petr Struve, had been a famous journalist in Russia since before the turn of the century. For a while he supported Marxism, was in contact with Lenin and Plekhanov, and was even exiled to Tver in 1901. Then: emigration, membership in the Kadet Party, teaching, return to Russia, Duma deputy... He headed the magazines Russian Thought and Polar Star. There was hardly a job he didn’t hold.

Struve did not accept the Bolshevik Revolution. He tried to fight against the new regime on the Don in the Volunteer Army under General Kornilov, but he was not meant to be a soldier. In 1918 he went abroad again. Eventually he settled Paris where he gave everything he had to his "brainchild" — the newspaper Vozrozhdenie.

The newspaper is fascinating. Today its archive is held in the Princeton Historic Newspapers collection. Take the time to go there, although be prepared to get carried away. You might stay among the volumes for weeks.

As culinary historians, we were naturally interested in stories about food, of which there are many. For many years the newspaper had a column called "Advice to Hostesses,” written, like everything in the paper, in pre-Revolutionary orthography until 1939. There are also absolutely charming texts like this one:

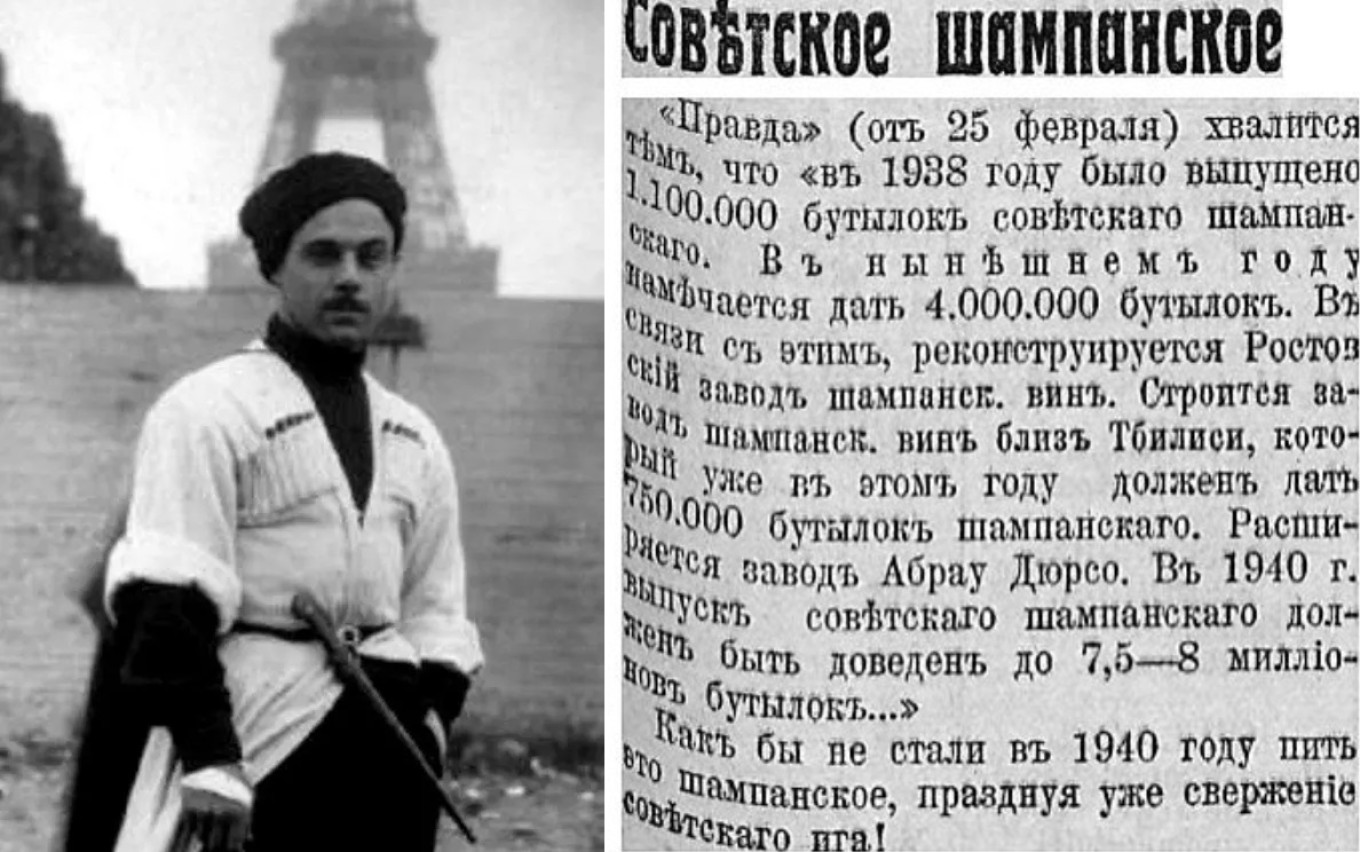

"The newspaper Pravda boasts that 1,100,000 bottles of Soviet champagne were produced in 1938. This year the plan is to produce 4,000,000 bottles. To this end the Rostov Champagne Wine Factory is being reconstructed. A champagne factory is under construction near Tbilisi, where they should have drunk all the champagne in 1940 to celebrate overthrowing the Soviet yoke!"

Vozrozhdenie never hid its political position. For obvious reasons, it did not have its own correspondents in Russia. But news and information got out one way or another. Vozrozhdeniye journalists would analyze Soviet newspapers and draw their own conclusion. For example:

"Vechernyaya Moskva reported that vegetable trade was increasing in the capital's markets. Collective farmers brought into the capital 243 tons of potatoes, 465 tons of berries, and 26 tons of fruit. For a population of 4.5 mln over 10 days, that's 5.5 grams of potatoes a day. No one’s going to get fat on that!"

Even the official Soviet chronicle, if read carefully, could be turned into a weapon of struggle against the Soviet power. All you needed to do was add and divide the numbers:

"New prices for tea have been announced in Moscow. The cheapest Batumi tea will be sold for 11.25 rubles per 100 grams. That means that the population in Russia is forced to pay for tea 14 times more than the French and 22 times more than the British."

Historians will find in the newspaper fascinating material about life in Russian emigration and the emigrants' hopes for various events. The newspaper syndicated memoirs of prominent people from Russian pre-Revolutionary history that were not included in Soviet history textbooks. And there are photographs of everyday life.

As for the cuisine of the Russian emigration — you feel rather odd when you read the recipes. It is obvious that people tried to carefully preserve the memories of their culinary past. All that barley and pickle soup, suckling pig with horseradish, Easter kulichi and buckwheat pancakes brought back, if only for a moment, a sense of former life.

"The smaller a suckling pig, the the tastier it is, so get one that does not weigh more than 10-12 pounds. The pig can be prepared in two ways: take off the head, cut it lengthwise along the spine. One half could be roasted, and the other half could be made into aspic.”

A new country means new foods. For example, the recipe for rassolnik reads: “If you can find it, pour cucumber pickling brine to taste; if not, add lemon juice for acidity." The recipe for traditional cranberry kvass is next to one for the exotic banana jam.

French recipes were also given along with recipes for traditional Russian cuisine. These were not complicated recipes. Perhaps the compilers chose what had once been served in the homes of noble families or in the best restaurants St. Petersburg. Few Russians who came to Paris in those years had the means to dine in the Parisian restaurants listed below:

If you get a chance, leaf through those yellowed pages. In the words you can feel memory and pain, the emigrants' attempt to recreate at least a piece of their homeland in a foreign land — if only in sweet cheese pastries or roast goose with cabbage.

Ratatouille

Yes, it's a French dish. But it’s an ordinary rustic dish enjoyed by Russian émigrés, and there is nothing "haute cuisine" about it. That’s the way the French see it — a dish cooked by grandmother in the village. It’s a wonderful dish of stewed vegetables, not the name of a mouse in an American cartoon or synonym for glamorous life.

Ingredients

- 4 red or multi-colored peppers (red, yellow, orange; I don't recommend green)

- 4 small young zucchini or tatuma (green summer squash)

- 4 small eggplants

- 2 large sweet tomatoes

- 2 medium onions (preferably white)

- 4 garlic cloves

- olive oil

- salt, ground chili pepper (ideally espelette)

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 200°C/390°.

- Slice the onions thinly and dice the tomatoes. Put the onions on the bottom of a ceramic pot, top with tomatoes, salt and sprinkle with pepper. Bake for 15-20 minutes.

- Cut peppers coarsely, dice eggplants into large cubes and slice zucchini or squash.

- Drizzle the vegetables with olive oil and bake each of them separately.

- Press garlic and mix with olive oil, salt and pepper.

- Mix all the vegetables in the baking dish and season with olive oil and spices.

- Cover with baking paper and place in the oven for another 10-15 minutes.

- Add olives if desired.

Eat hot, warm or chilled - delicious either way.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.