Today this old manor house is almost abandoned and forgotten. Perhaps an old Roma curse still hangs over its walls. But only a little over a hundred years ago it was a home filled with life.

As drivers head towards Podolsk from the west, some may notice a village with a strange name: Sportbaza (Sports Camp). But few know that this Soviet name hides a real gem of the Silver Age. There is a training and sports center here. But a little further through the foliage you can see the bluish walls of a fairy-tale castle. If you approach it from one side, you will see only two floors. But if you go around the abandoned house you’ll see that the ornate but crumbling stucco rises up to another floor. The building is crowned by a tower with balconies in faux medieval style.

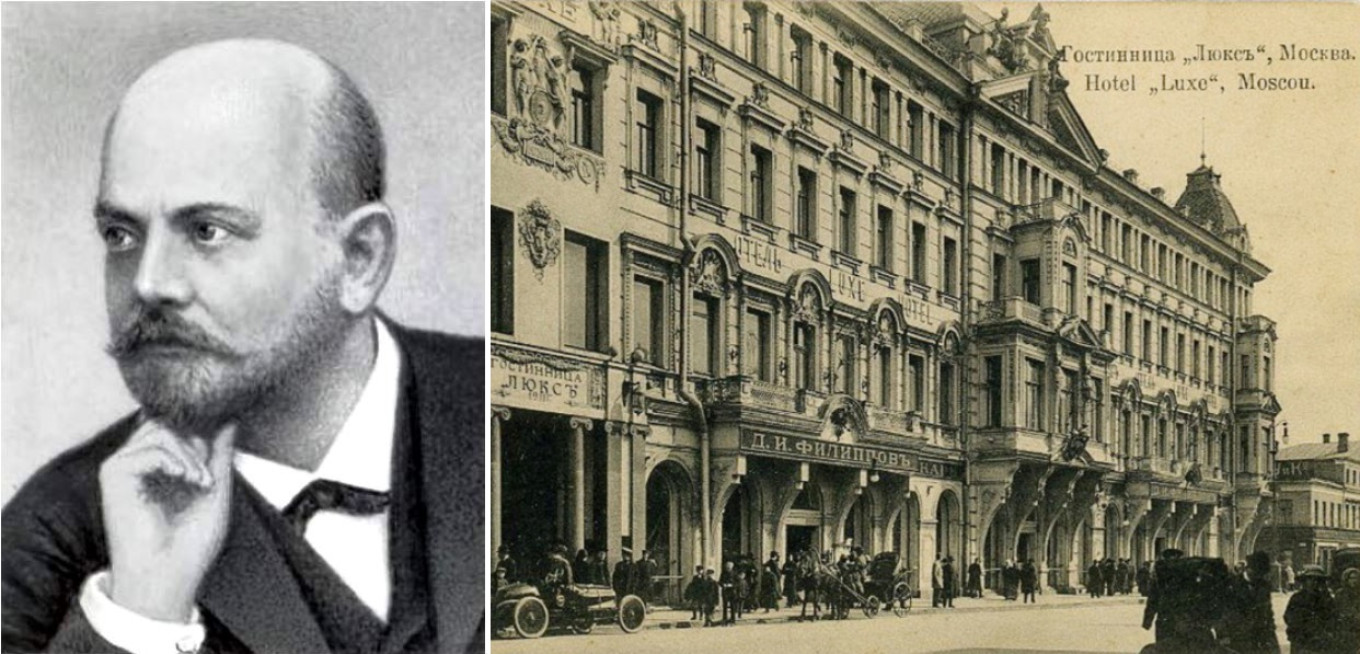

“That’s the baker’s house,” the security guard will tell you when he notices your interest. But he’s completely wrong, of course. Dmitry Ivanovich Filippov, the heir to an illustrious family, was clearly not a baker. But "Filippov's Bakery" on Tverskaya Street, known for its kalaches and saika buns since the mid-19th century, had become a large company with millions of dollars in turnover and dozens of stores by the beginning of the 20th century. Its assortment also included bagels, pies (filled with notochord – sturgeon spinal cord – cabbage, rice, raisins, apples, and other stuffings); dried goods and cakes. The business of the founder of the dynasty, former serf Maxim Filippov, was continued by his son Ivan (1824-1878). It was under him that the business flourished.

And it was Ivan who was the hero of a famous story about cockroaches told by writer Vladimir Gilyarovsky:

"In those days [1848-1859] the all-powerful ruler of Moscow was Governor-General Zakrevsky. Everyone trembled before him. Every morning hot saika buns from Filippov’s Bakery were served to him for tea.

One morning the Governor-General shouted to his servants over his morning tea. “This is an abomination. Send for the baker Filippov!” The servants, not understanding what the matter was, ran and brought back the frightened Filippov.

The governor handed him a saika bun with a cockroach baked in it. “What's that? A cockroach?! Tell me! What is it?”

“It's very simple, Your Excellency,” the old man said, turning the bun around in his hand. “That’s a raisin.”

And he took a bite of the bun with the cockroach.

“You're lying, you bastard,” the governor shouted. “Saikas don’t have raisins! Get out of here!”

Filippov ran into the bakery, grabbed a sieve of raisins, and dumped them into the baker's dough, much to the bakers' dismay.

Scholars now say that Gilyarovsky's memoirs weren’t accurate. But what is there to argue about? Even if it was talented journalistic fiction, it has already gone down in history.

After Ivan Filippov passed away, the firm "Ivan Filippov and Heirs" was established. The main bakery on Tverskaya Street went to his son Dmitry, who had his own firm with sixteen bake shops and bakeries. In the early 20th century, he rebuilt the main store (with the architect Nikolai Eichenwald), expanded the bakery and planned to build a hotel called "Luxe." A restaurant was opened in a hall designed by P.P. Konchalovsky and S.T. Konyonkov. Later, in 1916, there was a fashionable cafe under the extravagant name "Pittoresk" here. It opened in the evening with a performance of Blok's play "The Stranger."

By the early 1900s, Filippov's Bakery on Tverskaya had become the "Main Shop of the Bakers to the Imperial Family."

Unfortunately, this building at 10 Tverskaya Street (Tsentralnaya Hotel) has been under reconstruction for many years. Since the early 1990s when it was first owned by a Russian oligarch and later by Georgian Prime Minister Boris Ivanishvili, the building was sold and resold. And the sluggish reconstruction seems to have no end at all in the current crisis.

But back in 1906 the place was packed with shoppers, wondering at the bizarre architectural elements and wall paintings. When Dmitry Filippov began the reconstruction of his store, he also had the idea of asking the architect Nikolai Eichenwald to work on his country house. The land he wanted to build on was near Podolsk on the steep bank of the Mocha River. It was here, not far from the remains of the ancient fortress of Peremyshl, that Dmitry decided to build his family home. The ancient ramparts of defensive structures built in the 12th century by order of Yuri Dolgoruky can still be seen nearby. A classic park, paths, pavilions and rotundas were created near the merchant’s new house.

Dmitry Filippov's life and fate were a kaleidoscope of successes and failures. In 1905 the firm went bankrupt, in 1915 (after Dmitry's death) it was again in the hands of the Filippov dynasty — until the 1917 Revolution. Dmitry’s personal life was an illustration of the phrase "a merchant bender." During one of his nights on the town he met a gypsy who changed his life. Aza sang with musicians at a club in Petrovsky Park.

The millionaire baker Dmitry was head over heels in love. He even dedicated his new house to her, his “Roma Madonna.” Maybe her ideas about beauty were reflected in the architectural details.

You'll forget Moscow and Peter,

You'll forget everything about me.

But I'm the best Russian baker,

And you’re the finest gypsy!

But love doesn't always last. Filippov's new girlfriend soon replaced Aza in his life. It is said that Aza climbed up into the tower of the country house near Podolsk, wept for a long time, and then threw herself out of a high tower window.

Today, only Veronika Dolina's poem, which became her song "Gypsy Aza,” remind us of that long ago story.

The "best Russian baker" Filippov is remembered not only for his famous saika buns, but also for his other wonderful pastries. This pie is like a metaphor for his life: a bit wild, rich, and overflowing.

Blueberry Pie with Lemon Glaze

Ingredients

For the short crust pastry:

- 200 g (7 oz or 1 ¼ c) flour

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 100 g (3.5 oz or 7 Tbsp) room temperature butter

- 1 egg

- 75 g (2.5 oz or 2/3 c) sugar

For the filling:

- 500 g (generous 1 lb) blueberries

- 3 stale pieces of white bread

- 100 g (3.5 oz or ½ c) high fat sour cream

- 90 g (generous 3 oz or ½ c) sugar

- 2 eggs

- zest of 1 lemon

Instructions

- If the blueberries are frozen, half an hour before making the pie take the berries out of the freezer and defrost. If blueberries are fresh, wash and dry.

- For the dough, sift the flour and baking powder into a bowl, add the softened butter, sugar, egg, and knead everything thoroughly but not too long. Then wrap in cling film and put the dough in the refrigerator for 1 hour.

- Grind the white breadcrumbs into crumbs. If you don't have breadcrumbs, you can grind plain cornflakes.

- Preheat the oven to 190°C/375°F.

- Whisk together sour cream, egg, 75 g of sugar and lemon zest. For this cake it’s better to use high-fat content sour cream: it whips better and and holds onto the cake as a glaze. If you wish you can replace sour cream with full-fat cream cheese.

- Assemble the pie: grease a pan (26 cm/10 inch) with removable sides, roll out the dough on a lightly floured table or board to fit the pan. Place in the baking tin and crimp the edges. You can just lay it out in the cake tin and pat it in place using your (well-floured) hands. Sprinkle the bottom of the pie with bread crumbs and add blueberries, leaving 10-15 berries for decoration. Top the blueberries with the sour cream and egg mixture.

- Put in the oven and bake for 15 minutes, then add the blueberries put aside and bake for another 25-30 minutes. Sprinkle the cooled pie with the remaining sugar.

- The pie is best eaten slightly warm. It can be served with whipped cream.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.