For the outside observer, Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to be riding high on a wave of national support and euphoria following the Wagner rebellion. Immediately after the June 23-24 mutiny, the Kremlin’s PR team shifted into high gear to hide its weaknesses and demonstrate that everything — as always — is under control. Below the surface, however, it is growing increasingly apparent that much is not going according to plan.

On July 7, the independent Levada Center pollster published statistics from the end of June arguing that Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny and march on Moscow did not negatively affect the Kremlin’s approval ratings, but may have even strengthened public opinion toward the Russian authorities. Though there are a number of methodological issues with wartime polling — and polling in Russia in general — the Levada Center numbers are likely representative of the success of the Russian authorities in controlling the media space and reclaiming the post-rebellion narrative. That being said, it is highly unlikely that little, if anything at all, will go back to normal.

Firstly, Putin as an actor seldom reacts to the world around him. Rather, he weighs the possibilities brought to him by his advisers and the few remaining people that still have access to him, meticulously planning his next moves. Yet just days after the rebellion, Putin was walking amongst the crowds in Derbent, Dagestan, mingling with ordinary citizens, taking selfies, and acting as if he was on the campaign trail. For a president who has spent the past two years distancing himself from everyone around him, forcing those that he will see in person to quarantine for two weeks — and centering much of his rule above the common folk — descending into a crowd of thousands is a notable break with former praxis.

Being jostled from event to event, smiling and euphorically speaking to the public, armed forces, politicians, and business leaders, Putin is clearly on the defensive. This new, reactive Putin, in contrast to the former cool, distanced boss, is far more susceptible to manipulation from those around him. Putin’s aloofness and detachment from most current events in Russia, including Ukrainian drone attacks on Moscow, could permit actors close to the president to push their own agendas, thereby escalating political infighting to new, destabilizing levels.

Secondly, despite the severity of the crimes committed by Prigozhin and Wagner in rising up against the state, the Kremlin is hardly doing anything to punish those responsible for what amounted to the greatest threat to Putin’s rule in 23 years. Exiling the former and dissolving the latter may be effective in solving that problem, but they only lead to a weakening of Putin’s image in the eyes of those around him — and those with grander aspirations. The Kremlin is taking a more forgiving tone in order to avoid further publicity and quickly move past the unfortunate — but not all too problematic — days of yore. This may be effective for the immediate future, but it is more likely to have the effect of emboldening actors within the siloviki looking for career advancement. In other words, Putin’s recent actions have opened the doors to dissent among his inner circle and the country’s security forces, which are in a permanent battle for influence. Over 23 years, Putin has created a system of rule in which the strongest comes out on top. Exhibiting weakness will not bode well for him.

Finally, Tatiana Stanovaya, a Carnegie Eurasia fellow and founder of R.Politik, argues that for Putin, his image has always been of second-rate importance. Though this is true, it is also an axiom that for countless Russians, the image of a strong, iron-willed leader is of primary importance. For decades Putin has cultivated the persona of the archetypal Russian man: tough, exacting, bare-chested, and even ruthless. Throughout Russia’s war against Ukraine, and foremostly following the Wagner rebellion and Putin’s reactions, that image has begun to crack. If Putin can no longer project the image of a macho man who is in control of the situation and rules with an iron fist, but rather that of an aloof, reactive pensioner feebly responding to the world around him, his carefully curated persona begins to fall apart. Whether this is true or not is hardly relevant; for many Russians who are beholden to populism and the politics of imagery, disillusion is on the horizon. Stanovaya went as far as to refer to this as a “severe blow” to Putin and the state.

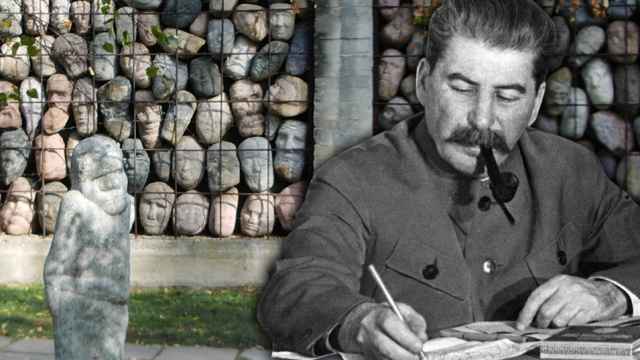

In the end, for Putin’s inner circle, Russians en masse, the entire Ukrainian army, and the West, Prigozhin’s rebellion happened under Putin’s watch. Tanks drove through Rostov-on-Don, Wagner soldiers marched to Moscow, and the world’s largest country was brought to a standstill by a few hundred armed militants. Statistics will not mask that reality. Even Stalin’s paintbrush will not be able to erase that blunder from the memories of Russians and anyone growing tired of Putin’s outdated, weakened, and costly rule. Although this may not have immediate political implications, it opens the door to a significant challenge to Putin himself and his system of semi-totalitarian state control in the future. The once-infallible regime and the carefully choreographed imagery it created have begun to crack.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.