Moscow and St. Petersburg are old rivals, and not only for the title of capital city. They even argue about food and what to call it. For example, Muscovites call gyros "shaurma,” but in St. Petersburg they are called “shaverma.” Another big argument is what to call a doughnut: ponchik or pyshka? In the northern capital, they are called pyshka.

Many people today would say that a ponchik is just a round piece of fried dough while a pyshka always has a hole in it. Tens of thousands of restaurants and cafes in Russia would argue with this because they do the opposite. Moscow’s oldest doughnut shop near VDNKh has been making ponchiki since the 1950s. And their ponchiki have holes. These doughnuts sprinkled with powdered sugar and have been delighting visitors for decades.

Some experts believe the hole is an issue. “A ponchik with a hole is nonsense. It’s like borsht without beets or shashlik cooked in a frying pan,” writes Svyatoslav Loginov, a well-known researcher of this topic. Unlike his other works — he is a well-known writer of fantasy in Russia —his work on the doughnut question is not in the realm of fantasy. He does, of course, realize that the whole — or hole — topic is somewhat comical.

But were there ever differences between ponchiki and pyshki? Pyshki have been around for centuries. The name is derived from the verb пыхать which meant “to fry in oil.” So we can consider pyshka native to Russia.

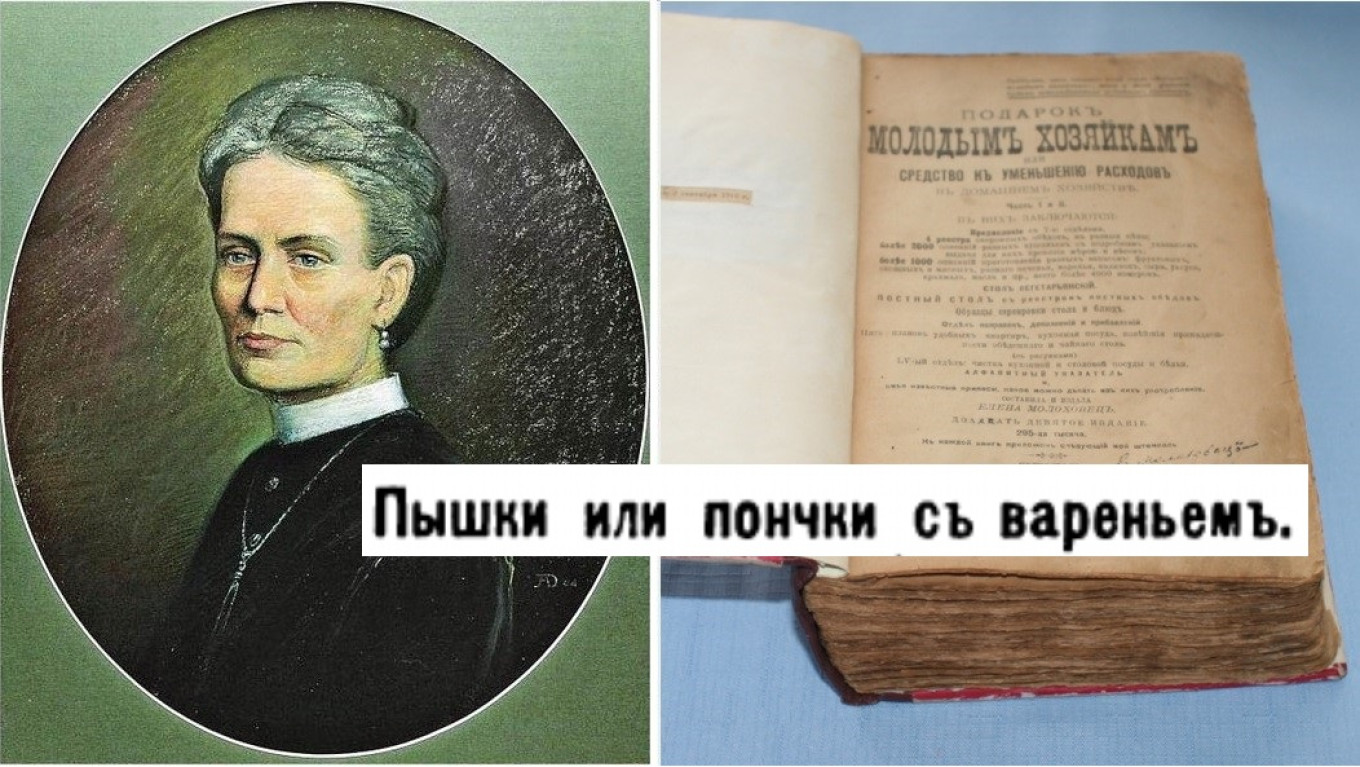

But there are some questions about ponchiki. Not many people know that this popular treat came to Russia from Poland not long ago. Yelena Molokhovets was one of the first to use the word "ponchiki" in the second half of 19th century. And that was when the battle between pyshki and ponchiki began.

In the old days ponchiki were an entire symphony of tastes and scents. Little ponchiki made with yeast dough and filled with rose hips — pierożki — were described by Stanisław Czerniecki, the author of a cookbook published in Cracow in 1682. He recommended filling them with elderberry jam, plum jelly, apple or pear jam and even poppy seeds.

But back to Molokhovets. She herself was quite influenced by Polish cuisine. And many of the recipes in her "A Gift to Young Housewives" were actually of Polish origin. That is why we were not surprised to see the name of one of her recipes: "Pyshki or ponchki with jam."

Notice that she calls them ponchki, not ponchiki. This isn’t a typo. She lists a half dozen more recipes of ponchki with rum, apples, chocolate, and other fillings. These ponchki don’t have holes; they are just balls of dough with fillings. Molokhovets makes no distinction between pyshki and ponchiki (or ponchki).

No holes are mentioned in pyshki in another work from that era as well, "Home Economics for Young and Inexperienced Hostesses" by A. Shambinago published in Saint Petersburg in 1860. Here the pyshki have no holes at all: "With a spoon, slip pieces of yeast dough with raisins into a saucepan with boiling clarified butter. When they brown, take them out, put them on a platter and sprinkle with sugar."

After the 1917 Revolution, jealousy between the old capital and the new one intervenes in the dispute between the pyshka and ponchik. This is when people began to argue over the origins of this pastry – Leningrad or Moscow. But there were still no holes. "The "Technical Manual" of 1936 contains the following recipe: "The piece of dough is cut in the same way as for other fried pastries with the only difference that after it is filled with jam, the edges of the pastry are gathered into a knot and rolled by hand into a round shape.”

You see: both ponchiki and pyshki are just balls of dough with jam filling inside. So when does a hole appear? We first encounter it in Russian sources in the first edition of "The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food" of 1939. Its authors instruct home cooks to "roll out the prepared dough half a centimeter thick, cut out circles with a glass. Cut out the middle of each circle with a smaller glass, giving the dough a ring shape.” These were called “Moscow ponchiki.” And it seems that this started the city-to-city rivalry.

But we have our own version of why the hole in the ponchik appeared at this time. Doughnuts aren’t just a Polish or Russian pastry treat. The traditional American donut — with its traditional American spelling — has that hole in the middle. What, you may ask, is the connection with Russia? It's simple.

Since 1934, the People's Commissariat of Food Industry in the USSR was headed by Anastas Mikoyan. In 1936 he visited the United States to learn about the latest food-processing methods. During this trip he bought many new technologies and brought to the U.S.S.R. (store food wrapping, quick freezing, ready-to-cook products, canned food, etc.). A number of new products also appeared, including ketchup and hamburgers — which were later called "Mikoyan meat patties." It seems that donuts-with-a-hole were part of the technology transfer.

Unlike our traditional doughnuts, American donuts are, as a rule, made from special dry mixes and the finished products are covered with glazes and sprinkles. But donuts are as popular there as they are here. There is a worldwide fraternity of doughnut lovers, a passion that seems to unite all people on Earth.

Everything that is deep-fried has a special, extraordinary ability to make your mouth water. But they are also a nutritionist's nightmare. So you can experiment with doughnuts, too. For example, we bake them in the oven instead of dropping them in a deep fryer. They are just as delicious!

Oven-Baked Doughnuts

Ingredients

- 350g (12.3 oz or 2 ¾ c) wheat flour

- 182g (6.4 oz or ¾ c) room temperature milk

- 1 large egg

- 30g (1 oz or 2.1 Tbsp) room temperature butter

- 1 tsp dry yeast

- 2/3 tsp salt

- 75g (2.6 oz or 2/3 c) sugar

To decorate the doughnuts

- 60g (2 oz or 4.2 Tbsp) melted butter

- Powdered sugar mixed with spices of your choice: cinnamon, or a mixture of cinnamon, nutmeg and coriander

Instructions

- Pulse flour, milk, eggs, oil, yeast and salt in the bowl of a food processor. The dough is quite firm at first.

- Divide the sugar into three or four parts and add, pulsing continuously.

- Continue pulsing/kneading until the dough is smooth and elastic.

- Grease a bowl with butter.

- Transfer the dough to the bowl and leave to rise for 3 hours.

- Punch the dough down twice, once at 45 minutes and then at 90 minutes.

- Divide the dough into 8 portions of about 75-80g (2.6-2.8 oz) each. Roll them out, cover with clingfilm and let rest for 20 minutes.

- Line a baking tray with baking paper.

- Transfer the dough pieces to the baking tray, flatten with the palm of your hand and use an oiled finger to make a hole in the middle. Place donuts at least 5-6 cm apart since they will expand considerably as they rise. It is better to place them on 2 baking trays. Stretch them out slightly, giving the shape of a doughnut. Don’t worry – they’ll puff up when they bake.

- Cover donuts with cling film and leave to rise for 1.5 hours.

- Meanwhile preheat oven to 180°C/350°F.

- Bake the donuts in the preheated oven for 20 minutes.

- When they are done, brush the hot donuts with melted butter.

- Sprinkle with powdered sugar when slightly cooled but not cold.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.