General Mikhail Skobelev was a hero of the Russian-Turkish war (1877-78) and liberator of Bulgaria. But in addition to his military exploits, he left his mark on our cuisine. That was quite a feat considering that he was not a gourmand and, in fact, never ever guessed that he’d go down in history for his culinary merits.

In 1878 when the battles were over and the Bulgarian land was liberated from the Turks, it was time for Skobelev to return to Russia. In parting, legend has it, the general lined up local volunteers and presented awards to the most deserving.

“Enjoy your lives working on your liberated land, my Slavic brothers,” he said.

Then a Bulgarian with a St. George medal on his chest stepped forward. “We have nowhere to work, Your Excellency. The Turks burned our villages and stole our cattle.”

“What's your name, hero?” asked the general.

“Ivan Kozlar. I’m one of five brothers…”

“I came here from the Turkestan region,” Skobelev said thoughtfully, “where cities are beginning to grow. You Bulgarians are excellent farmers. The people there are hard-working, the land is rich. What do you say, hero?”

Skobelev spoke the truth. He really knew Turkestan firsthand. In 1868 he had been sent to Tashkent, where he was an officer of the headquarters of the Turkestan military district. As commander of the Siberian Cossack squadron, he was involved in hostilities on the troubled border with Bukhara. In 1873, "to release our countrymen languishing in grievous captivity," he prepared an attack on the Khanate of Khiva. Skobelev, commander of the vanguard, distinguished himself during the capture of Khiva. At the end of the Khiva campaign Lieutenant Colonel Skobelev and a group of Turkmens carried out a reconnaissance mission deep into the country that was remarkable for courage and bravery. The daredevil Skobelev was awarded the Order of St. George 4th degree.

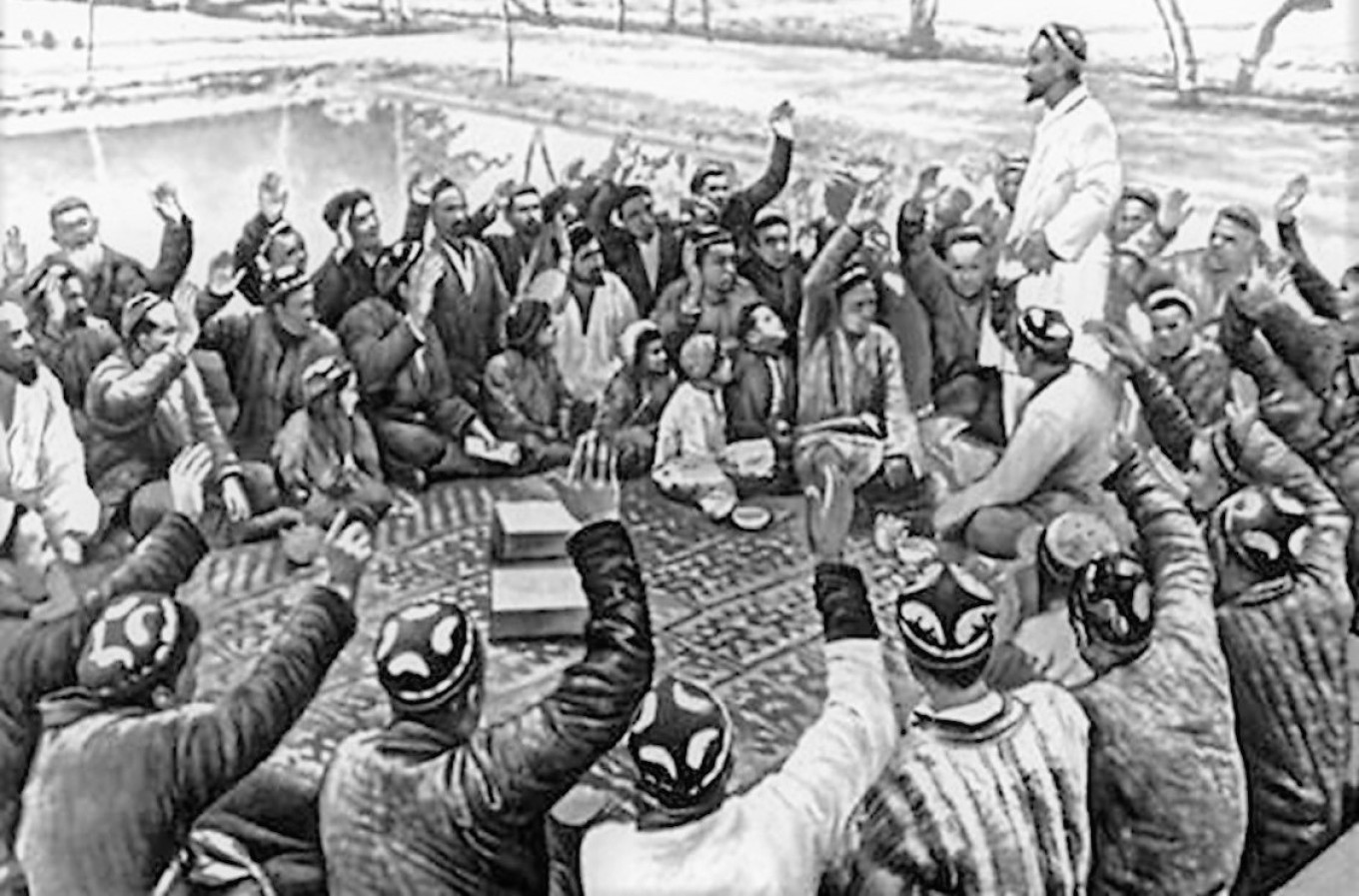

At the end of May 1875, he was again deployed to Turkestan, where the Kokand rebellion had broken out. Skobelev was promoted to the rank of Major-General for his actions. For defeating the enemy in Balykchy on November 12, he was awarded a sword with the inscription "For courage.” For serving with distinction in the Kokand campaign, Skobelev was awarded the Order of St. George, 3rd class, and a golden sword decorated with diamonds.

In distant Bulgaria Skobelev was reminded of his youth fighting in Turkestan. That is where he sent the Bulgarian soldiers. And that's how it all began. A few years later a large convoy of Bulgarians led by Ivan Kozlar arrived and settled not far from Tashkent. They set up their homes near the village of Sarykul. Bulgarians, like Uzbeks, are hard-working people who get settled quickly. They took no time to make themselves at home. The sixth "brother" in the Kozlar family was a Russian soldier, Ivan Potekhin.

Before their arrival, local farmers had planted onions, carrots, radishes and hot peppers. The Bulgarians brought seeds of tomatoes, eggplants, cabbage, and sweet peppers, and began to cultivate potatoes. Eggplants had been grown here in the past, but they were the semi-wild Afghani variety. But tomatoes and sweet bell peppers were quite a novelty. Soon Uzbeks in the neighborhood started to plant "Bulgarian" vegetables. And Abdulla Yusupov, the neighbor of the farmers who settled here, made friends with them and became an honorary member of the family.

Almost forgotten events are not as far away as they seem. In the fall of 1925, the Soviet leadership of the republic called upon the old vegetable growers to form collective farms. Ivan Kozlar and Abdullah Yusupov, who were already over 70 years old at the time, laid the first stones in the huge collective farm greenhouses. In 1931, they both passed away, but people remembered them and the mass cultivation of vegetables on Uzbek land.

Do you think that this is the end of their story? Not at all. When we were reading the magazine "Ogonyok" in December 1966 we found a surprising fact. Adyl, the son of Abdulla Yusupov, continued his father's business. The vegetable grower was 70 years old in 1966, and he was, like his father, showered with honor and respect. Adyl Abdullayev worked as an agronomist in the experimental greenhouse farm of the Republican Scientific Research Institute. And most of the new vegetable crops were created by him on the basis of varieties imported at the end of the last century by the Bulgarians settlers.

When we published this story in social media a few years ago, we did not think there would be a sequel. But quite a few people have written to us that even today you can hear the expression "Bulgarian vegetables" in Tashkent. And the new high-rise buildings built in the 1980s was also called "Bulgarian vegetable gardens."

You might think: "The Russian-Turkish war! That’s ancient history! That was all long ago!” But history is sometimes very close — just stretch out you hand and you can touch it.

Skobelev's name has remained a part of Russian cuisine. During the universal patriotic enthusiasm that accompanied Russia's entry into the First World War, the Moscow English Club served a dish named after this brave general. We know this from a menu surviving from October 15, 1914, that offered diners “Skobelev meat patties with peas.”

We don’t know whether Mikhail Skobelev (1843-1882) was a lover of fine food. It is unlikely that he had anything to do with this dish. It was a tribute to a soldier who had brought glory to the fatherland on the battlefields. It was invented by the cooks of the Moscow English Club, which was famous for its excellent cuisine.

Skobelev’s meat patties are filled with mushrooms (truffles in the original) and traditionally served with baked potatoes, pickles, or potatoes baked in milk. Of course, you can forget about fiddling with the patties and just serve them with mushroom sauce. But we wanted to stay close to the original recipe. The original recipe also suggested using a red sauce with mushrooms. You can use that or a simple béchamel or sour cream sauce.

Skobelev's Mushroom Filled Meat Pockets

Ingredients

Patties

- 800 g (1 lb and 12 oz) veal or chicken (shin or breast)

- 150 ml (2/3 c) 10% (light) cream

- 100 g (7 Tbsp) melted butter

- 150 g (6 oz) white stale wheat roll or bread

- 1 egg yolk

- salt, black pepper to taste

- breadcrumbs (homemade)

- clarified butter for frying patties

Filling:

- 100 g (4 oz) mushrooms

- 50 g (2 oz) wheat flour

- 50 g (2 oz or 3.5 Tbsp) butter

- 200 ml (5/6 c) cold milk

- 1 egg yolk

Garnish

Potatoes, pickles

Instructions

- Run the veal or chicken meat through the meat grinder twice together with a wheat bun soaked in milk.

- Put the minced meat in a bowl, add the cream left over from soaking the bread, egg yolk, melted butter, salt and pepper. Knead the mince until completely homogeneous. Put it in the refrigerator for 2 hours.

- Then cut the minced meat into pieces weighing 100-120 g (3.5-4 oz) each and form them into round patties.

- Bread the patties in breadcrumbs and sauté in heated clarified butter for 5-7 minutes on each side.

- Prepare the filling: boil the mushrooms and chop finely.

- Heat butter with flour and dilute with milk, stirring constantly with a whisk. Simmer for about 10-15 minutes.

- Add chopped mushrooms and egg yolk to the sauce; stir.

- Preheat the oven to 170°C/340°F.

- Carefully slice off the top (“lid”) of each patty. Then use a spoon to make an indentation in the bottom part of the patty, being careful to keep thick enough “borders” so that the patty doesn’t fall apart.

- Put the minced meat spooned out from the bottom patties in the sauce with mushrooms. Stir to mix.

- Put the filling inside the patties and cover with the “lids.”

- Place the filled patties in a baking dish or tray and put in a heated oven for 10-15 minutes.

- Serve with potatoes and pickles.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.