At Easter in Russia eggs are dyed different colors and blessed in church on Saturday. Then on Easter morning the hard-boiled eggs are eaten for breakfast. But first everyone at the table picks up and egg and challenges their neighbor to a duel: they smash the eggs together. No one understands the meaning of this today, but everyone is inexplicably delighted when their eggshell doesn’t break and their neighbor’s is cracked.

The Russian Easter egg ritual is not very ancient. The first documentary evidence of the egg roll game at Easter dates back to the 14th century, and egg breaking contests were not mentioned until the 17th century. Meanwhile, monastic edicts of the 17th century categorically prohibited them all.

It’s actually hard to draw conclusions from this. It is clear that the egg played a symbolic role in our ancestors’ lives in pre-Christian times. There is no mention of this in the Russian chronicles, which indicates that eggs were part of pagan rituals and beliefs almost until the 15th century. After that, these customs were adapted to church life. A similar story happened with blinis, which had no connection with Shrovetide and the last week of Lent until the 16th century.

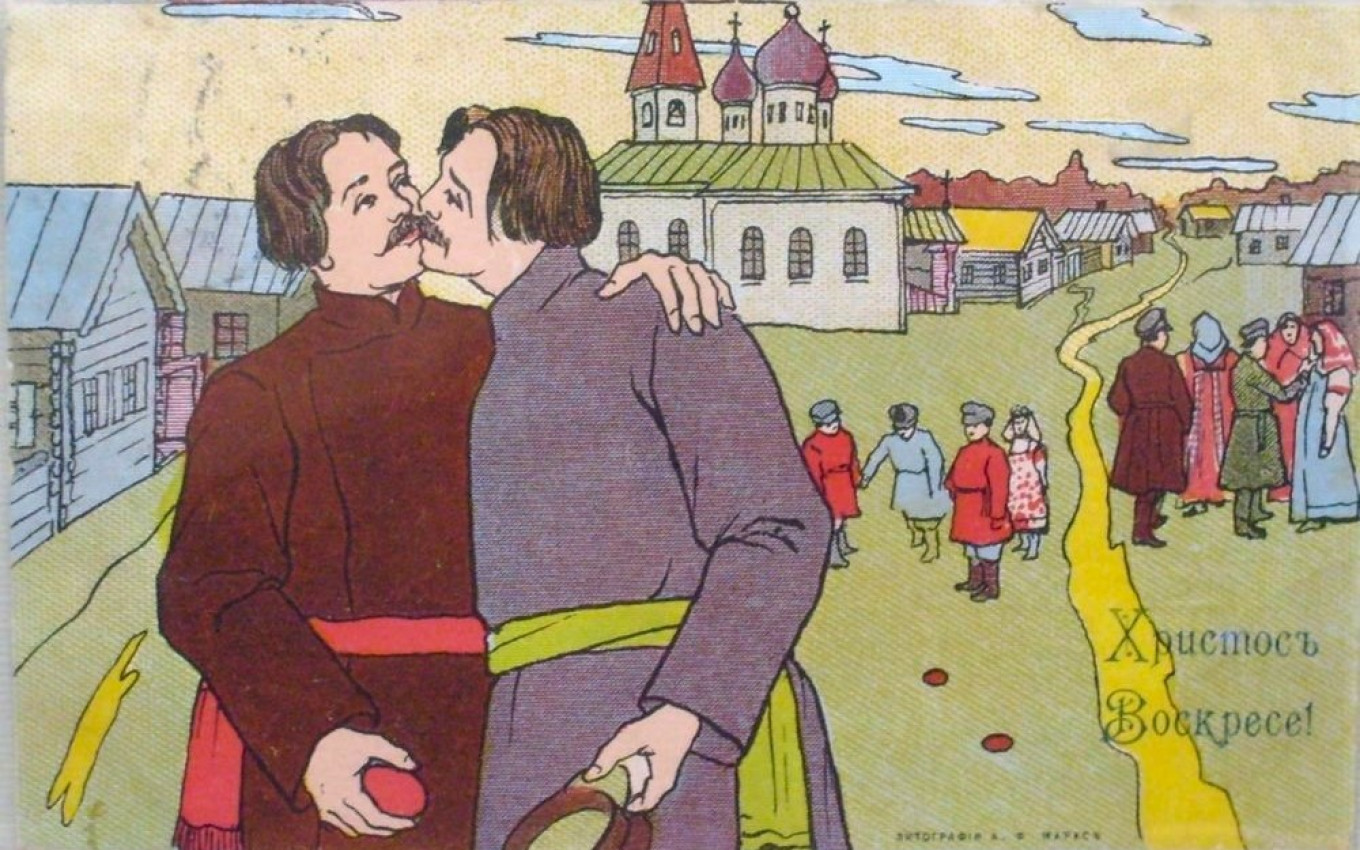

It was European travelers who wrote about the custom of dying eggs in Moscow: Siegmund von Herberstein (visiting Russia in 1526); Jacques Margeret (in 1600-1606); Peer Persson de Erlesunda (1608 and 1611); and others. In the 17th century, as historian Nikolai Kostomarov (1817-1885) wrote, "all through Holy Week throngs of people sell red eggs or sometimes gold-painted eggs. Some were goose or chicken eggs, and some were wooden. When people exchanged Easter kisses, it was customary to give an egg, and if people of unequal position were exchanging the Easter kiss, the egg was given by the higher to the lower.” The “exchange of Easter kisses” is the traditional Easter greeting: One person greets another with "Christ is risen!" The other person responds, "Truly he is risen!" And they kiss each other three times.

But as you can see, there were no egg smashing contests. Of course, this doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist. In fact, if there were clerical prohibitions, then it means whatever was being prohibited was happening! But it is another matter that the practice was discouraged in public.

Red was the most popular color for Easter eggs in pre-revolutionary Russia. They were dyed with onion skins, which turned the eggs red-brown. Red dye was obtained from cochineal, that is, from carmine coloring that was made from the cochineal beetle. The dye was deep crimson with a purple tinge and very expensive. Yellow dye was made from the roots of wild apple trees or elderberry flowers, which were boiled with eggs, as well as onion skins. A plant known in the south of Russia as mouse hyacinth (Muscari armeniacum) produced a blue dye. It did not have to be dried beforehand, as it was already blooming in the south by Easter. If you boil eggs in this dye, they will turn dark blue, almost black. In Alexander Kuprin's story "In the Family," the heroine recalls her childhood in the countryside and Easter. She says they dyed the eggs with onion skins, rags and a decoction of "dream-grass," which produced a blue color.

Eggs boiled in buckwheat husks were indigo. A decoction of dried mallow flowers could also produce a beautiful blue. Alder bark produced black dye. People must have stocked up on and dried the herbs they needed for the spring dyes the previous summer.

To decorate eggs dyed with onion skins, people wrapped the eggs in the skins and then pieces of cloth. Sometimes they would put stencils of dried herbs under the skins — a technique still used today. In our family we use the roots of rose madder (Rubia tinctorum). Just before Easter dealers from Georgia, where the plant is called “endro,” bring the roots to Moscow. It produces a rich burgundy-red color.

Interestingly, the most detailed descriptions of Russian Easter were made by Germans. German — and more broadly European — travelers, merchants and diplomats left records of the real Russia of the distant past. Russian authors described only the deeds of the saints and the exploits of the princes.

Herberstein's "Notes on Muscovite Affairs" were written when Moscow did not even have printed books yet. Now these are the real “old days!” Even in the 19th century, Germans had images of Russian life that were much more detailed and photographically accurate than that of domestic anthropologists.

Here we see a book of stories from Russian folk life for children, published in 1882. But what is it? Its bright, colorful illustrations are actually "luminous, colored original paintings by Scherer and Engler” in Dresden.

In 1863 the German Martin Scherer and the Swiss Georg Nabholz organized a joint venture in Moscow, buying the studio of Carl Bergner ("Photographie de A. Bergner à Moscou"), which was very well-known at the time. The firm did photographic portraits, business cards and exhibition catalogs. As often happens, it is thanks to foreigners that unique pages of our history have survived: photos of Decembrists who returned from exile, famous writers, artists, musicians and public figures of the time.

The photographic studio was given the highest award; it was granted the right to place the image of the Russian coat of arms on its products. Martin Scherer did the first photographic panorama of Moscow, which is still the best documentary panorama of the Russian capital.

Soon afterwards, however, Scherer the business and sold the firm in 1867. He left for Dresden, where he founded the M. Scherer & H. Engler photographic firm. It’s this company’s work we see today. How this German firm captured Russian Easter so exactly!

Of course, people loved Easter for lofty reasons, but the women of the house loved it for a practical reason, too. Where do all these hard-boiled, colored eggs go afterwards? This may not solve all your leftover egg problems, but here’s a family recipe to help you along.

Beet Pickled Eggs

Ingredients

- 6 eggs

- 1 large beet

- 200 ml (5/6 c) apple cider vinegar

- 2 Tbsp sugar

- 1/2 tsp salt

- 1 Tbsp mustard seed

- 1/2 Tbsp black pepper

- 2 Tbsp dried Italian herbs

- 1 red onion

- 1 avocado

- juice from 1/4 lemon

- 5 Tbsp mayonnaise

- salt and pepper to taste

- herbs for garnish

Instructions

- Cut the beets into 0.5 cm thick slices.

- Pour water, vinegar, sugar, salt, mustard, pepper and herbs into a saucepan.

- Put on the stove, bring to a boil, turn down the heat and cook for 15 minutes over a low heat. Remove from the heat, leave for 30 minutes.

- Boil eggs for 8 minutes, remove from heat and leave in the hot water for 8 more minutes. Then drain the water and peel the eggs.

- Place the eggs in the beet marinade, add sliced red onion. Leave it for 24-48 hours.

- Finely chop the avocado.

- Take the eggs out of the marinade, carefully cut in half and remove the yolk.

- Mash the yolk with avocado. Salt and pepper to taste; add mayonnaise and lemon juice.

- Fill the egg halves with the yolk mixture.

- Decorate with red onion and dill sprigs.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.