"The rabbit is Stalin's bull." This ridiculous slogan of the early 1930s is almost forgotten today. But at the time it was emblazoned on the front pages of newspapers, on posters and enormous street banners. Like the poems of Vladimir Mayakovsky and "Red Square" by Kazimir Malevich, this slogan encapsulated the mood and ideology of the era.

Food shortages almost always plagued the Soviet people. Before WWII, there were only a few years in the early 1920s with relatively good food supplies. The new economic policies stimulated private enterprise and promoted food production. But the needs of industrialization soon forced the authorities to look for a source of funding. They focused on the peasantry, forcibly driving them into collective farms. The result was soon felt. By 1929 ration cards were introduced in Leningrad for bread, cereals, sugar, butter, eggs, meat, and potatoes.

And just two years later in 1931, new words entered the vocabulary of Leningraders. A "closed worker's cooperative" was a store at an enterprise. The worker of the plant or factory was "attached" to it. There, he could "trade in" part of his "ration book" (the buyer's main document) — that is, he could buy food and goods at state prices.

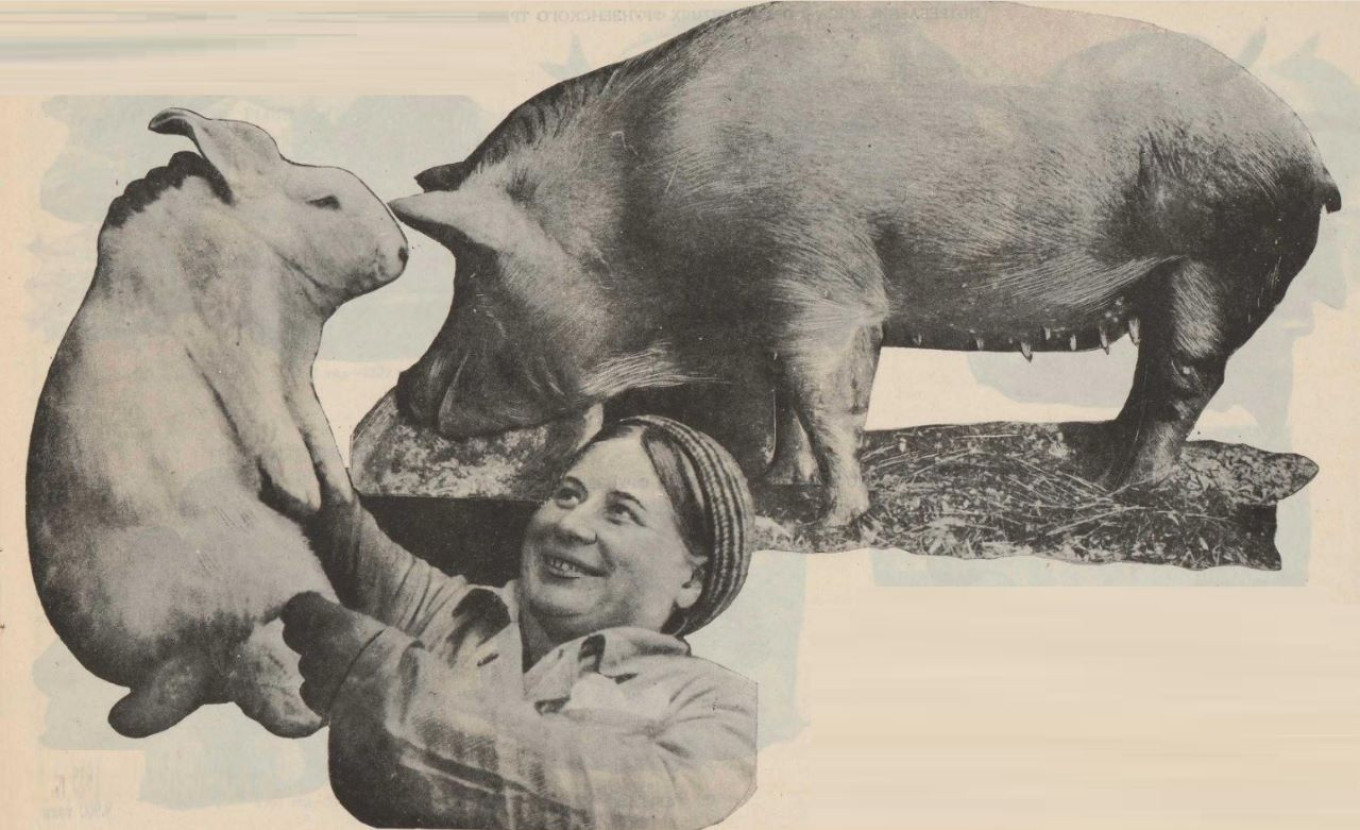

In this dire situation, the authorities began to search for alternative sources of food. One source was rabbits. "You can literally do wonders with rabbits," Sergei Kirov, the leader of Leningrad, declared in 1931. And gave the order to raise the number of these animals to 220,000 in a year.

Journalists pushing the party line began to explain all the benefits of this meat that was not historically part of Russian people’s diet. The magazine "Worker and Peasant Woman" wrote: "Rabbit meat is white and delicious. If necessary, it can be preserved, salted or smoked. The head, skin, and feet make a delicious aspic."

Rabbits weren’t touted as the only salvation of townspeople. There was also a campaign to breed more goats for milk. There was even a slogan: "The goat is the worker's cow.” Tables comparing the productivity of cows and goats were hung on the walls of all institutions. "A peasant’s cow produces 60 buckets of milk — three times its own weight. But a goat produces 10-15 times its own weight!"

There was a simple explanation for this propaganda campaign: collectivization had sharply decreased the number of cows in the country. The domestic cows which had been herded into collective farms either died of starvation or produced several times less milk.

In those years knowing what can be eaten when there is nothing to eat was precious information. Rabbit meat was still a delicacy. What about dolphin fillet or breast meat, for example? At that time the "Five-Year Plan for Public Catering" stipulated sending to canteens completely new products: soy milk, milk sugar, albumin pastilles (a product made from cow blood) and dolphin meat. They also sharply increased production of margarine and lard. This was not the Italian products we are used to today. Back then it was simply the lowest quality pork fat melted in ovens and steam boilers.

All of this went primarily to the canteens of Leningrad which, in those years, were the only places where people could eat more or less well. After all, even in Leningrad in 1931 the monthly norm of meat for workers was one kilogram. White-collar workers had an even smaller norm. And if you belonged to the nobility or merchant class before the Revolution, now your social category was called "disenfranchised." This meant you were not allowed to buy any products at state prices. So the rabbits glorified by state propaganda came just at the right time.

In the late 1930s Ogonyok magazine wrote about a special Party directive: "Deployment of rabbit breeding is at the top of today’s battle plan.” “At the largest plants of the Soviet Union the fight for rabbit breeding begins." The magazine reported about the start of a socialist competition unheard of before." “The 10th Anniversary of October Factory began construction of a pen for 2,000 rabbits." This was all self-service animal husbandry: the construction of rabbit houses and breeding of long-eared rabbits were to be done by the workers themselves.

The Soviet leadership pinned great hopes on rabbits: "By the end of 1937 the number of rabbits was to increase to 40 million, which would amount to 20 percent of the total meat supply in the country."

It would seem that the rabbits had to work hard: "The ratio of females to males should be 1 to 10." But no, under Stalin the animals were taken care of: "The work norm for a male is no more than two females per day."

Alas, the fascinating description of the personal life of rabbits is beyond the scope of our article. Let's focus on their culinary use. In general, one rabbit can be used to cook three dishes at once. Make a soup out of bones and ribs, make a stew out of the filet. And the remaining parts can be used for rillettes — a kind of potted meat that is a delicious spread for morning toast. We don't think the proletarians in Leningrad indulged in it. But nothing prevents us from making this marvelous dish today.

Rabbit Rillettes

Ingredients

- 1 hind leg of rabbit (with thigh)

- 2 rabbit front legs

- 2 garlic cloves

- 1 shallot

- 1 bay leaf

- Sage 1/3 tsp

- Thyme 1/3 tsp

- Butter 1 Tbsp

- Meat broth (rabbit, poultry)

- Salt, ground black pepper to taste

Instructions

- Chop the onion finely, mince the garlic.

- Sprinkle the herbs over the rabbit legs, add onion and garlic, salt and pepper and mix. Cover with cling film and leave to marinate for 3 hours.

- Put marinated rabbit legs in a heavy-bottomed saucepan, add butter and a little bit of meat broth.

- Bring to a boil over medium heat; turn down the heat and cook for 2-3 hours over very low heat until soft. The meat should come off the bone.

- Cool a little and pull the meat off the bone with a fork and then mash it. Put the meat in a jar and pour in some of the broth in which the rabbit was stewed. Remove the bay leaf and put it in the refrigerator.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.