Buzhenina is one of the most delicious and ubiquitous main courses at holiday feasts. You might find it on a royal table or in a traveler's backpack. It can be served piping hot, just from the oven, or nicely cold — perfect for a painful morning hangover.

One of the first references to buzhenina is found in Domostroi (1650s): "Starting with the holiday of the Intercession, ducks are roasted in a simple onion sauce and nourishing dishes are served: thick pancakes, 5 for each dish; thin pancakes; sausages; pork kidneys; pig’s head with garlic; buzhenina.”

It’s not at all surprising to see buzhenina in a list of rich and fatty dishes. After all, what was the ideal meat for people in medieval times? Pork, of course. There is always plenty of it in a household at the height of the fall season. It is prepared to be stocked up for the long winter ahead in sausages, salted pork and, of course, buzhenina.

So what exactly is buzhenina? Vladimir Dahl's dictionary defines it as “pork, salted or smoked, ham with onions and other seasonings.”

The origin of this term is also understandable, if not immediately obvious. Fasmer's Etymological Dictionary derives it from words in various Slavic languages: Ukrainian "vuzenina," Czech "uzenina," etc. All of them mean a kind of smoked meat or ham.

Buzhenina is one of Russian cuisine’s basic traditional recipes. Every housewife had her own secrets for cooking this uncomplicated dish. Here, for example, is one of the first mentions of buzhenina in Russian cookbooks, in Vasily Lyovshin’s "Russian Cookery" (1795):

Take a good pork hock, that is, fresh pork; wash and dry it, stud it with garlic cloves cut in half. Rub the meat with minced garlic, keep it for a day in a deep container covered with kvass. When you want to cook it, remove the skin and roast it in the oven. Serve with garlic minced in sour cream.

A more refined version of this dish is found in the middle of the 19th century in the works of our well-known gastronome Ignaty Radetsky. For preparation of suckling pig buzhenina he uses speck "sprinkled with spices and minced garlic," bastes the suckling pig with oil and stews it in a pot. When it becomes “ruddy,” the piglet is basted in broth and its own juices until done.

But let us immediately dispel the myth that buzhenina is just a pork hock roasted in an oven. Yes, it is roasted meat, but not necessarily the leg. And buzhenina can be made from any kind of meat.

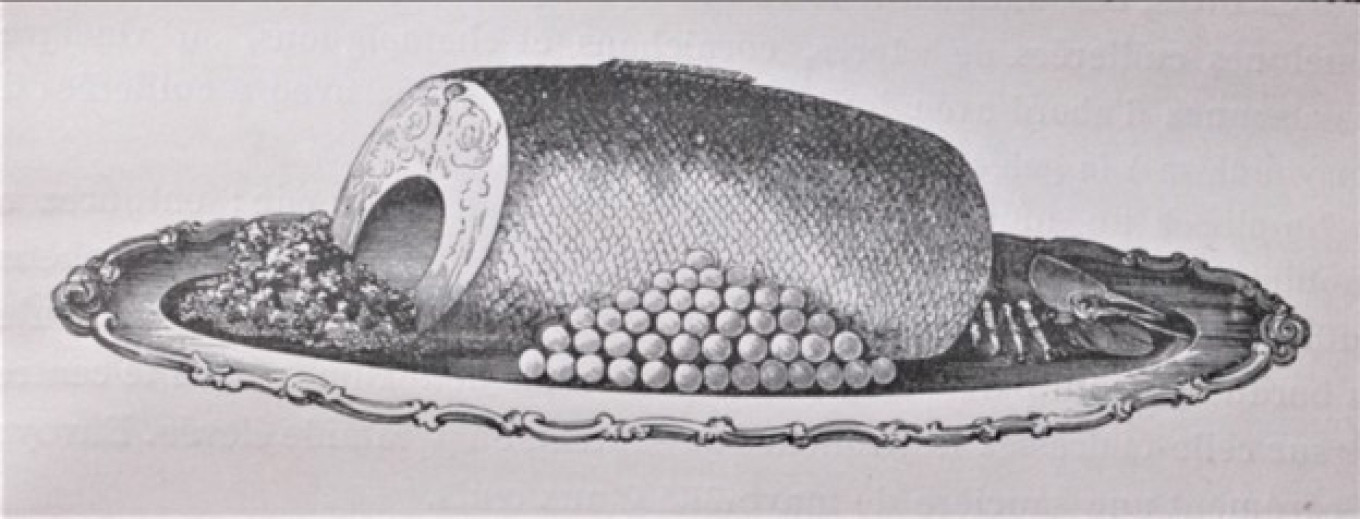

Buzhenina is more of a cooking method than a dish in traditional Russian cuisine. In Russia it was even made with fish (sturgeon) and turkey. Here’s an 18th-century recipe from Nikolai Osipov, the author of one of the first Russian cookbooks. Note the size of the portions in an ordinary landowner's household: a pood (16 kg or 35 pounds) of sturgeon and a bucket of vinegar!

Fish buzhenina: Cut a pood of fish into pieces, wash in cold water, put them into a pot of boiling water and keep on the fire till the vertebrae fall off. Then remove all the cartilage. Meanwhile, boil a bucket of vinegar and add peppercorns, ginger, aromatic garden herbs and finely chopped garlic. Add the fish and bring to a boil, then toss in some salt and cook until tender. Take the fish out of the pot, and while hot put it into another container, cover it with the hot broth from the first pot without the herbs, cover and put in the larder.

In the book "The Last Work of the Old Blind Man Gerasim Stepanov," published in 1851, you can read about turkey buzhenina. It was written by a remarkable man who began working in Moscow taverns when he was just a boy. Over the course of a half a century he rose to become chef in some of the capital’s most famous elite restaurants. He published five very useful cookbooks — the last one dictated as he was almost blind.

We really like this recipe. We adapted it a bit and traditionally make it to see out the long New Year holidays. Today we celebrate “Old New Year.” After the Gregorian calendar was introduced in Russia in 1918, “old” Christmas in Russia and other countries is January 7, and the night of January 13 to 14 is New Year's Eve "old style."

Turkey Buzhenina (Marinated and Seasoned Roast Turkey Breast)

Ingredients

One turkey breast, approximately 1 kilo (2.2 lbs)

For the marinade

- For 1 liter (quart) water

- 60 g (3.5 Tbsp) salt

- 100 g (1/2 c) sugar

For baking

- 1 Tbsp prepared mustard — preferably home-made without vinegar

- 1 Tbsp vegetable oil

- 1 tsp paprika

- 1/2 tsp red hot pepper

- 1/2 tsp freshly ground black pepper

- 1/2 tsp ground coriander

- 2 cloves garlic

- 1 bay leaf

- Add any seasoning you like: honey, soy sauce, rosemary, thyme, aromatic herbs.

Instructions

- A day before you want to serve the meat, boil water with sugar and salt, let it cool, add the turkey and leave it to marinate for 3-4 hours. If you wish, 1/3 of the water can be replaced with beer, kvass, white wine, apple juice or other liquids; they will give the meat extra flavor and aroma.

- When the time is up, take the turkey out of the marinade, blot with paper towel and leave it for a little while on a cooling rack to dry. Discard the marinade.

- Cut the garlic into small wedges, make slits in the turkey and insert the garlic. Mix spices with oil and mustard and spread it on the turkey with a pastry brush. Place a bay leaf on the filet and wrap in foil. Place in the refrigerator until the next day.

- Three hours before cooking, take the breast out of the refrigerator and let it come to room temperature.

- Preheat the oven to 250˚C/475˚F and place the turkey still in foil in the hot oven. After 10 minutes, turn down to 170˚C/340˚F.

- Cook for 1 hour and 30 minutes. The internal temperature of the breast should be 74˚C /165˚F.

- If you wish, before removing the breast from the oven, you can unroll the foil and put it under the grill for 7-10 minutes to give a crispy crust.

- Cool the buzhenina in the foil and then cut into thin slices.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.