Ushnoye is yet another mysterious Russian dish that culinary experts are still arguing about. We decided to be detectives and investigate it through the centuries of Russian cookery.

The famous Russian lexicographer Vladimir Dahl defined it this way: "Ushnoye is a meat or actually any kind of broth, stew, or a hot dish made of meat or fish.” He added the notation “old.” He also cited a very old Russian saying: Beetroot telnoye or turnip ushnoye is the food of a miser.”

It would seem that the saying refers to the ratio of vegetables to meat in the dish, and how there are more vegetables when money is tight or stores are low. But Dahl notes absolutely correctly the combination of flavors that were traditional for these dishes. You can guess that telnoye, a fish dish that we wrote about here, was served with beets in the past — beets and fish complement each other beautifully — while the ushnoye was stewed with turnips.

But of course there can’t be one exact ancient recipe. Before the 1830s and 1840s, Russian recipes did not indicate pounds, minutes or temperatures. This isn’t a question of what measures of volume to use. A classic 18th-century Russian recipe goes something like this: "Take a chunk of beef, pound it with an axe head until it falls apart, crumble some tsibuli (onions) and pecherits (the Russian name for mushrooms) on top, and put it into the oven until cooked."

Ushnoye is a very vivid example of this confusion. To this day, culinary experts and historians are still arguing over whether it is a soup like a chowder or a stew. With his definition Vladimir Dahl doesn’t resolve this dispute at all. But in fact, the dish allows for a variety of interpretations. Here, for example, is Vasily Lyovshin's recipe from the book "Russian Cookery" (1816):

“Mutton brisket or ribs, cut into pieces, boiled in water with onions and carrots, or with cut up turnips, then thickened with lightly browned flour.”

Is it a soup? Or is it meat in sauce? The only hint of clarity is that the recipe is published in the section of "hot dishes or soups.” But the confusion persists. In 1788, Sergei Drukovtsov published one of the first Russian cookbooks. He included a recipe for ushnoye under the section “soups.” So it would seem we have our answer: ushnoye is a soup.

But not so fast… In Drukovtsov’s “soups” section he lists cabbage soup and noodle soup along with “nyanya,” lamb stomach stuffed with buckwheat groats similar to haggis, chicken with grains and ham, kidneys with cucumbers, quail with cabbage and boiled goose. These are all dishes of meat and sauce. So the ushnoye mystery remains.

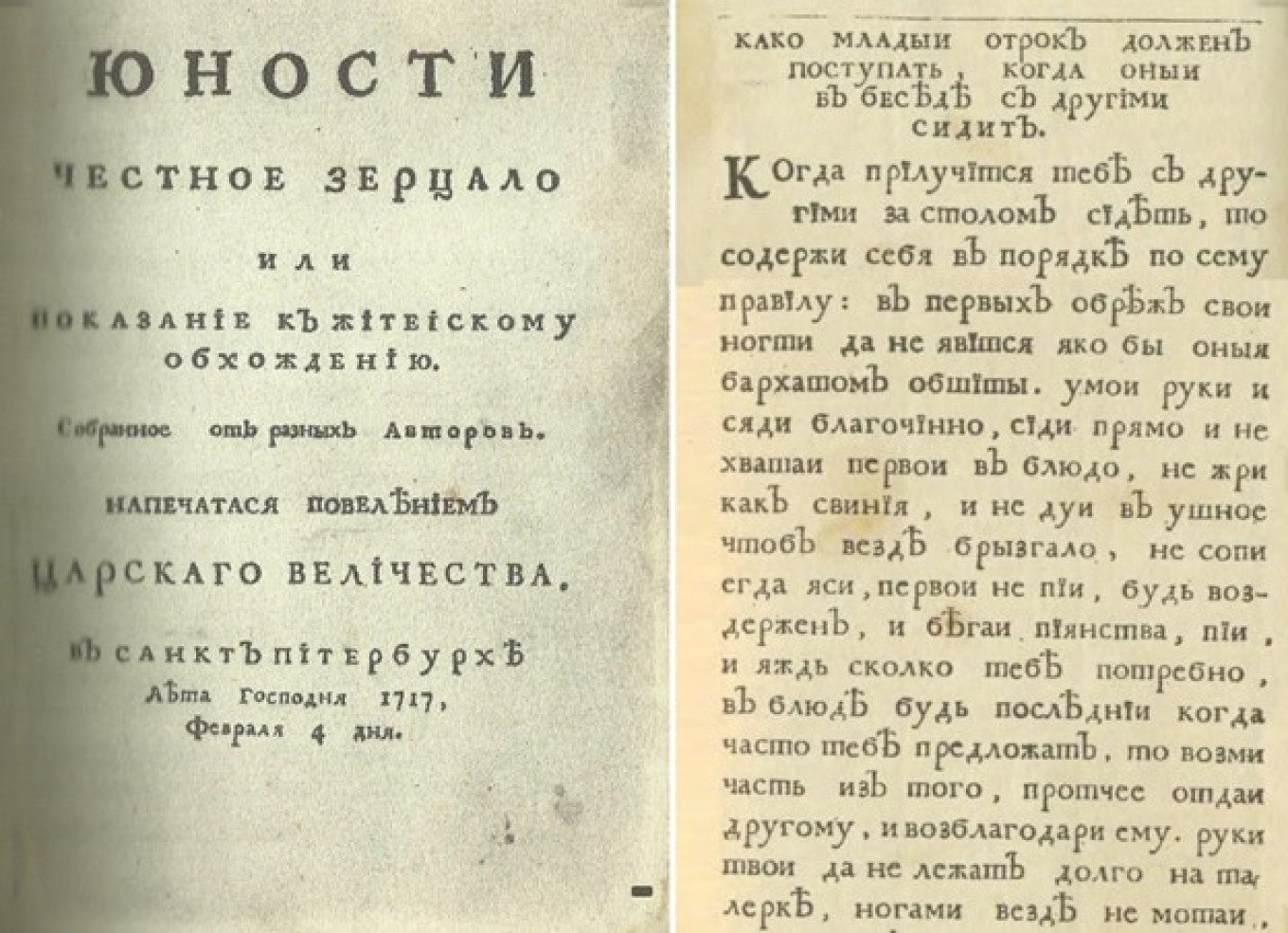

Let's go further back in time. "An Honest Mirror of Youth" is a literary and pedagogical work of the early 18th century that Peter the Great ordered for the education and upbringing of the children of the nobility.

The book contain much helpful advice, such as: “Don’t walk with your mouth open like a lazy donkey.” There is another very interesting set of instructions:

"When you sit at the table with others, behave according to these rules: first, trim your nails, so that they do not appear to be covered in velvet, wash your hands and sit nicely, sit straight and don’t grab the first dish, don’t eat like a pig, don’t blow on the ushnoye so that it splashes everywhere.”

Can you blow on soup so hard that it splashes everywhere? Maybe, but it’s easier to splash by blowing on meat in a thin sauce. It’s not that effective to blow on a bowl of soup, but you can cool down a piece of lamb by blowing on it. And you can get carried away and splash your neighbor in the process.

Monastery books also confirm that ushnoye is not soup: "April 20, 1656. Alexander's Day. White breads, cabbage soup or ushnoye made in a skillet, kvass, fish, porridge." This is a fragment from the Cellarer’s Handbook (instructions for a monk in charge of the household) at the Kirillo-Belozersk Monastery. Ushnoye made in a skillet is definitely not a soup. Note that Alexander's Day falls during Lent, so the ushnoye had to be made of fish.

All this leads us to a simple conclusion: ushnoye is somewhere between a soup and main course. It could be made in a pot or a skillet. The broth that the meat or fish was cooked in gradually evaporated. The broth was further thickened by the addition of slightly browned flour. Vegetables — onions, carrots, turnips, turnips — gave it the desired taste and consistency. Sometimes when the ushnoye was cooked in the oven, cooks used the traditional technique of sealing the top with dough.

Where did the name of the dish come from? The word "ushnoye" comes from the same root as "ukha" and "yushka" that mean "broth" or "liquid." This root can be found in Proto-Slavonic juxa: in Proto-Indo-European it is yewHs-/yuHs.

When the famous first household cookbook, "Domostroi," was being written in the 1550s, ukha was the universal name for a broth made from meat, fish, or poultry. You can find recipes for "Chicken ukha" or "duck ukha" in old texts. At the same time, unlike other soups of old Russian cuisine such as kalya or shchi, few ingredients were added to ukha. A piece of meat or fish was simply boiled and then used in another dish.

So what was the meat taken out of the ukha called? According to the rules of the Russian language of that era, it was, of course, called ushnoye.

The lamb or fish taken out of the broth was put in a skillet or pot. Some broth was added, but not enough to cover the meat or fish completely. Vegetables and spices were added. And then it was all stewed slowly in the oven or on the stove.

You can find ushnoye in cookbooks and various other sources written in the 16th through 18th centuries. At the beginning of the 19th century, it appears less often in cookbooks. And the 1860s and 1870s it had almost completely disappeared from common culinary literature.

Why? The reason is simple. The dish did not disappear. But its ancient name was replaced by a name the public in cities knew better: "ragout."

But let's go back to the first versions of this ancient dish. What could be better on a cold and dreary November evening?

Ushnoye

Ingredients

- 1 kg (2.2 lb) meat (lamb or beef brisket, pork cheeks)

- 2 medium onions

- 2 small carrots

- 2 medium turnips

- 400 ml (1 ½ c) meat broth

- 3 Tbsp melted butter

- 2 cloves garlic

- Pepper

- bay leaf

- Salt, ground black pepper to taste

- Dill, parsley for serving

Instructions

- Cut the meat into 3x3 cm pieces. Chop the vegetables into small cubes.

- Fry the meat in heated oil and put it into a cast-iron or clay pot. Then fry the vegetables and add to the meat.

- Season with salt and pepper, add minced garlic, bay leaf and pepper and pour hot broth over it.

- Put it into an oven heated to 170˚C (340˚F) and cook for 2-2 1/2 hours. Serve with finely chopped parsley and dill.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.