Updates with details of the burial, quotes from mourners, background.

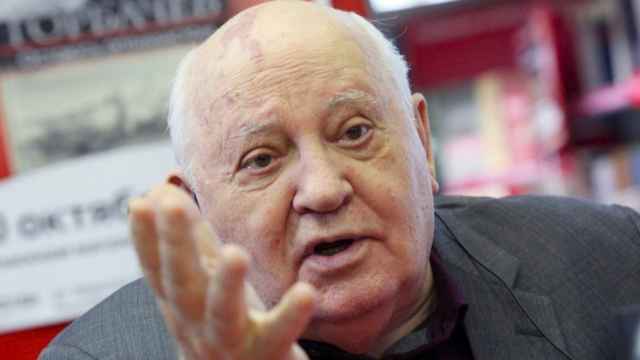

Last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was laid to rest Saturday in a Moscow ceremony, but without the fanfare of a state funeral and with the glaring absence of President Vladimir Putin.

Several thousand mourners queued up to quietly file past Gorbachev's open casket as it was flanked by honour guards under the Russian flag in the historic Hall of Columns.

The hall has long been used for the funerals of high officials in Russia and was where the body of Josef Stalin first lay in state during four days of national mourning after his death in 1953.

After several hours the coffin was taken out of the hall in a procession led by Dmitry Muratov, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning editor-in-chief of independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, which Gorbachev helped found.

The coffin was taken to Moscow's prestigious Novodevichy Cemetery, where it was lowered into the grave to the sounds of a military band playing the Russian national anthem and a gun salute.

Gorbachev was buried next to his wife Raisa, who died from cancer in 1999.

With Russia isolated by its military campaign in Ukraine, few foreign leaders attended what was a relatively low-key affair to remember one of the great political figures of the 20th century.

High-profile Russian attendees reportedly included Soviet pop singer Alla Pugacheva and former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, the current deputy head of the Security Council.

"It was a breath of freedom, which was lacking for a long time, an absence of fear," 41-year-old translator Ksenia Zhupanova said at the entrance to the hall where Gorbachev's body lay in state.

"I am against shutting us out from the outside world, I am for openness, for dialogue. This is what Mikhail Sergeyevich showed the world," she said, using Gorbachev's patronymic.

The mourners were of all ages, some old enough to remember the years of Soviet stagnation before Gorbachev came to power, others young enough to have only lived in Russia under Putin.

"It’s been six months since so many good people have been in one place,” said one mourner, according to a tweet by Guardian reporter Andrew Roth, an apparant reference to the February invasion of Ukraine and an accompanying police crackdown.

Flags were also flying at half-mast in Berlin on Saturday, in memory of the man who held back Soviet troops as the Berlin Wall fell in 1989.

In Russia, Gorbachev's steps towards peace and reform have been overshadowed by the economic troubles that followed the fall of the Soviet Union.

Putin, who called the Soviet collapse the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century, has spent much of his more than 20-year rule reversing parts of Gorbachev's legacy.

By cracking down on independent media and political opposition, critics say, Putin has worked to undo Gorbachev's efforts to bring "glasnost", or openness.

And with the launch earlier this year of the military campaign in Ukraine, he has sought to reassert Russian influence in one of the countries that won its independence when the Soviet Union fell apart.

On the streets of Moscow this week some expressed their continued anger and bitterness at Gorbachev, but those who turned up for Saturday's funeral paid tribute to his legacy.

"[Gorbachev] helped the development of the country, the bringing of freedom of speech and freedom of thought," said 19-year-old Irina Kaplanova.

He was not an "absolutely ideal politician", she said, but was "a great reformer, and a person who acted in accordance with their conscience and knew how to admit mistakes."

AFP contributed reporting.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.