What’s the difference between vareniki and pelmeni? Both are dumplings. Is it a question of who invented them? Even that is hard to decide. It’s amazing that passions are not raging over vareniki the way they are over borscht.

Almost every nation has its own kind of dumplings: Italian ravioli, Japanese gyoza, Georgian khinkali, Asian manti, and so on. But what’s the difference between vareniki and their closest relatives —pelmeni?

First of all, their fillings.

In vareniki, the filling is cooked in advance, for example, mashed potatoes or tvorog (similar to cottage cheese). Even if cooks put a meat filling in vareniki — which does happen — it is boiled or sauteed, not raw. Because the filling doesn’t need to be cooked, vareniki are boiled for a shorter period of time than pelmeni — just the dough needs to be cooked.

There are exceptions — for example, cherry filling isn’t pre-cooked. In Lithuania and Ukraine cooks have a popular recipe for vareniki made with raw potatoes, sometimes with a bit of uncooked salo (lardo, cured fatback).

Like salo and borscht, vareniki are considered part of traditional Ukrainian cuisine. But there is at least one other country where these dumplings are as popular — Poland. Poles call them pierogi. You can buy them everywhere, and the choice of fillings is endless. For example, you can find pierogi with spinach, a brynza cheese (like feta), or chicken. Pierogi lubelski are made with buckwheat groats, tvorog and onion. By the way, thanks to enterprising Polish immigrants, the word "pierogi" rather than "vareniki" entered many foreign languages. Every year a peirogi festival is held in Chicago, and in Canada they have a monument to pierogi the height of a three-story house.

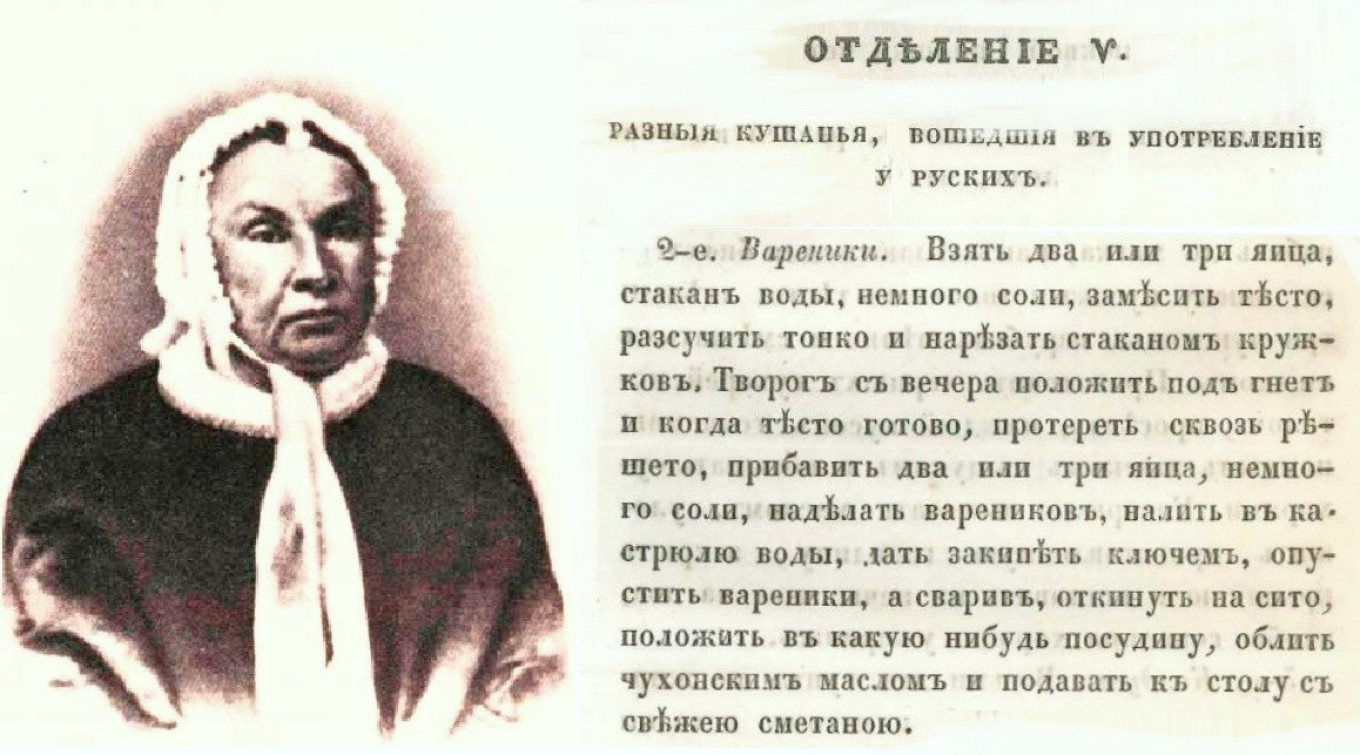

Ukraine has the widest variety of vareniki, but there are also many dishes from Ukraine in Russian cuisine. You can find a recipe for “Little Russian borscht and vareniki” in a cookbook by Yekaterina Avdeyeva from 1842. Note that the recipe for vareniki is in the section called “Various dishes that have entered Russian cuisine.”

Vareniki. Take two or three eggs, a glass of water, a little salt, knead the dough, roll it out thinly and cut into circles with a sharp-edged glass. Weight down tvorog the evening before, and when the dough is ready, press the tvorog through a sieve, add two or three eggs, a bit of salt, and make vareniki. Fill a pot with water and bring it to a rolling boil. Put the vareniki in, boil them, drain them and put it in a dish, top with butter, and serve with freshly made sour cream.

One of the most detailed descriptions of Ukrainian cuisine can be found in another book, the collection of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, "Proceedings of the Ethnographic and Statistical Expedition to the Western Russian Land," published in 1877. It has everything: meat and fish dishes, dairy, soups for lunch and dinner, fried and roasted meat dishes... and many kinds of vareniki.

Vareniki are made with cheese, poppy seeds, cabbage, with "urdoyu” (pressed hemp or poppy seeds), and with various kinds of berries, mainly cherries. Cooked as follows: Take wheat or buckwheat flour, add water to form thick dough, roll out on a table with a rolling pin, cut into squares, put some of the filling cited above in the middle and pinch close to form triangles. Cook in boiling water. Vareniki with cheese are eaten with fried salo or sour cream; vareniki with berries are eaten plain or with sour cream or honey; vareniki with cabbage or urdoyu are eaten with vegetable oil; vareniki with poppy seeds are eaten with honey. They are usually served at the midday meal, but during Pancake Week before Lent they are eaten almost every day.

In Ukraine cooks also make "lazy vareniki," called varenitsi. You make vareniki dough, roll it out and then cut it into small squares and boil them. After draining them, they are eaten with salo or sour cream. These vareniki “with the filling on the outside” are eaten at the midday meal, sometimes in the evening.

Ukrainians turned this simple dish into a vibrant symbol of their national cuisine.

But in old cookbooks you can also find recipes for “Old Russian vareniki” made with liver and sauteed dried mushrooms added to minced meat.

Now it's summer — berry season. Vareniki are made with cherries, strawberries and blueberries. Some cooks have even figured out how to make them with honeysuckle. How about currants — the black currants that we find by the bucketful at farmer’s markets and country houses? For some reason, they aren’t used as much in the Russian tradition. This is a complete mystery to us. Readers from Ukraine wrote us that their Poltava and Volyn grandmothers loved currant vareniki, made with a bit of sugar sprinkled on the berries before sealing the dough. Some cooks do the opposite — they add a bit of salty cheese to the currants. But this is in Ukraine. Although Russians adore currants, they never got into the habit of filling vareniki with them.

We looked through the archives and only found one mention of vareniki with black currants and apples produced in the 1960s. We suspect that the filling was grated to use up battered berries that couldn’t be sold otherwise.

Cherry vareniki

Even if we didn’t keep making currant vareniki, our cherry vareniki are a classic. Here’s our old family recipe:

Ingredients:

- 3 cups flour

- ⅔ cup water

- 1 egg

- a pinch of salt

- 2 cups of cherries

- Sugar to taste

Instructions:

Note: it is better to use cold water, otherwise the edges of the dough will quickly dry out and it will be harder to make form the vareniki.

- Mix the cold water with the egg and a pinch of salt. Pour a heap of flour on the table, make a well, pour in the water and eggs, mix in the flour, and knead until you have a stiff dough. Wrap in clingfilm and set aside for 40 minutes. After about 20 minutes, knead the dough and then let it rest again in clingfilm.

- Pit the cherries and sprinkle with ¼ cup sugar. Pick cherries that are sweet but flavorful — and not too large. Three berries should fit into each dough pouch. The sugar-covered cherries will produce some juice, which you can later mix with sour cream and spread over the cooked vareniki.

- We prefer to roll out a large piece of dough 2 mm (1/16 of an inch) thick and then cut out vareniki circles with a thin-edged glass. Do not roll out the dough too thin. If the dough is too thin, after cooking the vareniki will be an unappetizing shade of blue, and there should be the right balance of filling and dough. Put the leftovers together and roll out again. Some people like to make a roll, cut it into pieces and roll out each piece into a circle. This is convenient and also saves on waste.

- Drain the cherries in a colander but be sure to keep the juice!

- In the center of each dough circle put three cherries. Next sprinkle sugar over each filling according to your taste — just the tip of a teaspoon — and seal the edges tightly. Place the vareniki on a table sprinkled with flour.

- Fill a three-liter (approximately three-quart) pot about 2/3 full of water and bring to a boil. Gently lower the vareniki into the water, stirring carefully to keep them from sticking to the bottom. Bring to a boil again, and when the vareniki float to the surface, cook for another 3-4 minutes. Use a slotted spoon to lift them out.

- Place on a lightly buttered plate (to keep them from sticking) and serve with a mixture of cherry juice and sour cream, or simply sour cream.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.