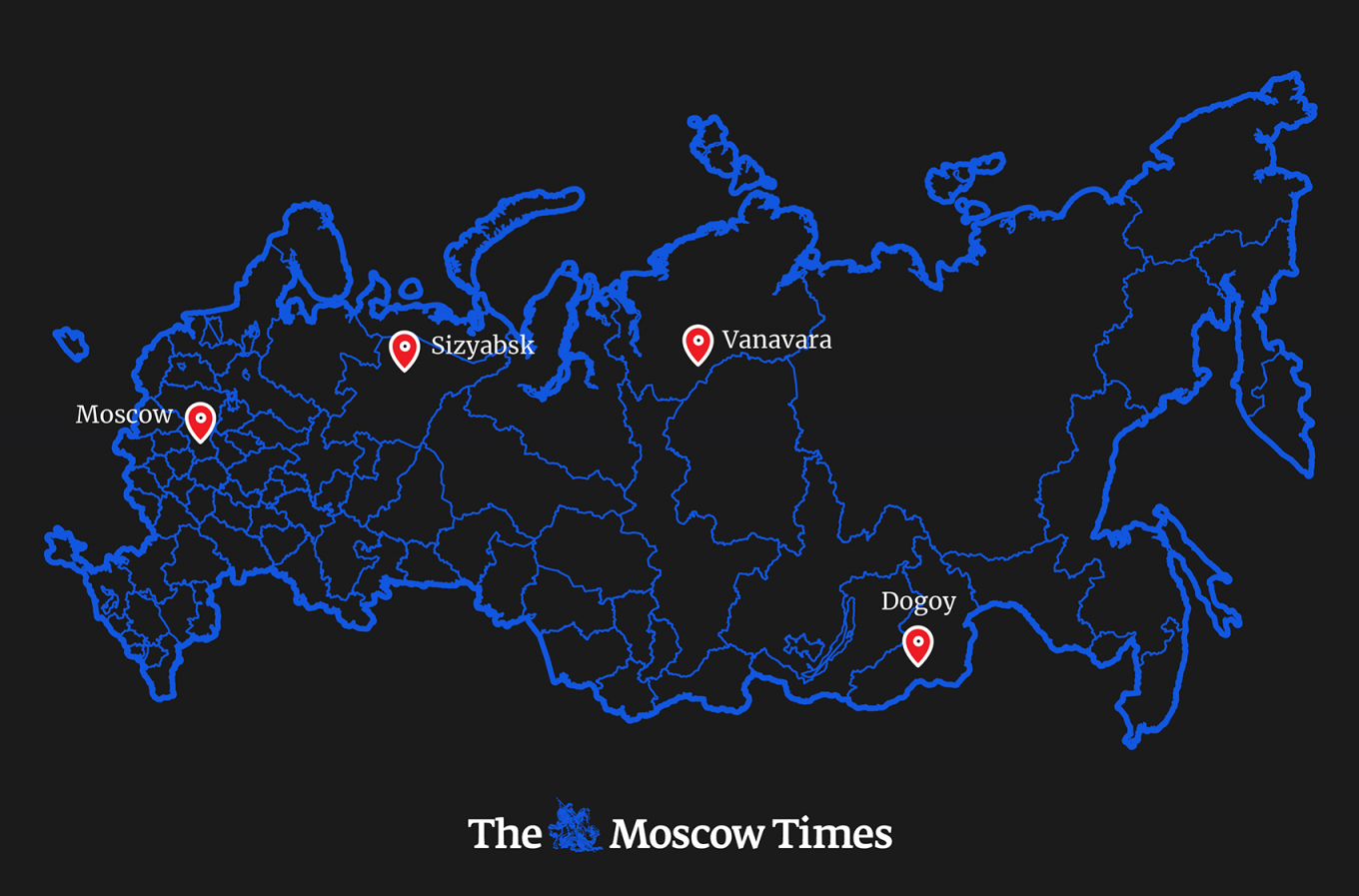

In the middle of the taiga forest more than 4,000 kilometers from Ukraine, even the remote Siberian village of Vanavara has felt the consequences of Russia’s invasion of its neighbor.

The authorities in May confirmed the death of Russian soldier Sergei Vasilev, 22, who was born in a settlement near Vanavara and spent several years attending a boarding school in the village together with his younger sister.

An ethnic Evenki, one of the indigenous peoples of eastern Siberia, Vasilev was killed in early May. It took nearly a month for his body to be returned to Vanavara from what locals refer to as “the big land.”

With no rail or road links, the only way in and out of Vanavara is by air or – in the summer months – on a boat down the Podkamennaya Tunguska River.

Eventually, the community held a memorial service at a local House of Culture, with Defense Ministry representatives and local officials in attendance.

“The place was packed with people and funeral wreaths. The boy was a native [Evenki] — one of us — which meant that even if we were not blood relatives, it was a personal loss for everyone,” a 24-year-old local told The Moscow Times.

The death of Vasiliev, who signed on as contract soldier in the Russian army in 2019, is a stark reminder of how the reverberations from Moscow’s bloody invasion of Ukraine have been felt in Russian regions thousands of kilometers from the fighting.

News of his passing spread rapidly among the approximately 15,000 inhabitants of the Krasnoyarsk region’s Evenkiysky district, where Vanavara is located, and which covers a vast tract of land in central Siberia that is larger than any European country.

“Until then, everyone tried to just ignore the war,” said the local, who requested anonymity to speak freely.

With the Russian Armed Forces relying heavily on the services of contract soldiers, the geography of the country’s losses in Ukraine has been disproportionately skewed toward more economically disadvantaged areas — particularly those populated by indigenous, non-Slavic communities.

“There are no jobs and no prospects [in remote rural regions]. Incomes are pathetically low,” said Tomila Lankina, a Russian politics expert at the London School of Economics.

“For these people, getting a contract to serve in the Russian army and fight in Ukraine offers unimaginable riches that they have never seen and their parents and grandparents have never seen,” she told The Moscow Times.

Stories of loss similar to that of Vasiliev in Vanavara have been unfolding in other towns and villages in distant corners of Russia since the start of the war in February.

Several people from the Zabaikalsky region village of Dogoi on the border with China are currently fighting in Ukraine, according to Dolgor, an 18-year-old-local.

“Serving in the army is the only way to make money,” said Dolgor, who requested that her surname not be used.

While Dogoi, a farming village almost 7,000 kilometers from Ukraine, has not yet experienced the death of any locals, many residents have friends and relatives who have lost loved ones.

“My relatives in [the neighboring republic of] Buryatia go to burial services every single day,” said Dolgor.

The Siberian republic of Buryatia and neighboring Zabaikalsky region are among the Russian regions with the highest numbers of military losses. A total of 164 soldiers from Buryatia and 102 from Zabaikalsky region have been killed in Ukraine, according to an independent tally of the Russian death toll in Ukraine by independent media outlet iStories.

In Dogoi, families whose loved ones are serving in Ukraine go to Buddhist monasteries every day to pray for the well-being of their relatives, according to Dolgor.

Despite the deaths, most of those living in remote regions appear to back the war.

“I was very surprised to learn that our native Evenki peoples support the ‘operation’ given that we are constantly fighting for the preservation of our forests and against discrimination from ethnic Russians,” the Vanavara local said.

Independent polling suggests that over three-quarters of Russians support the Kremlin’s military campaign in Ukraine.

“It is far more than just the material drivers like income [that motivate people to join the war],” said expert Lankina. “It’s about the feeling of deprivation and the ‘us’ versus ‘them,’ where ‘us’ is the poor people and ‘them’ is the liberal intelligentsia who were always privileged.”

Often without reliable internet connections, the only source of information in many remote regions is television, which dutifully relays the Kremlin’s narrative.

Although the northern village of Sizyabsk in Russia’s republic of Komi – where reindeer herding drives the local economy – gained some internet access several years ago, many locals still get their news from state-owned television.

Not only are residents of Sizyabsk largely supportive of the government, but they apparently remain unphased about the prospect of economic problems.

“Whenever I ask about the prices or availability of medicine, my relatives say that they are ready to put up with it and can grow anything they need in their backyard,” a woman whose extended family lives in Sizyabsk told The Moscow Times.

Internet access can only go so far in changing people’s worldview, according to Lankina. “Deprived young people [in rural communities]... grow up in families where the grandmother might still have been illiterate,” she said.

While the human cost of the Ukraine war in Russia may have been felt more acutely by poor, rural communities in remote areas of Russia, there are few signs of any desire in these areas for political or social change.

“Some people are crying and praying for the war to end but I haven’t noticed any actual resistance,” said Dolgor in the farming village of Dogoi. “But there must be someone who is against it. It cannot be that everyone is in favor.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.