BISHKEK, Kyrgyzstan - Aijamal Atakeldiyeva grew up in the Russian Urals city of Perm with only a passing knowledge of the Central Asian country of Kyrgyzstan, where her family is from.

But Russia’s war in Ukraine upended her life and forced her to seek temporary respite in the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek, over 2,000 kilometers to the south.

“I quit my job and decided to move here and find work,” Atakeldiyeva told The Moscow Times in an interview in Bishkek. She made the decision to resign and leave Perm when her salary was delayed by several weeks.

“I spent my entire childhood in Perm, finished school, graduated college — and this is my first time in Kyrgyzstan,” she said.

The invasion of Ukraine, Western sanctions and growing economic problems have created difficulties for the estimated 2.5 million Central Asia nationals who live and work in Russia, and many of them are now considering returning home.

Those who stay face layoffs, lower wages and fewer job prospects.

At least 133,000 labor migrants from Uzbekistan, Central Asia’s most populous country, have come back from Russia this year. And Tajikistan, the region’s poorest nation, has welcomed nearly 60,500 returnees since January.

The economies of Central Asian countries like Tajikistan are exposed to the knock-on effects of the war as they heavily rely on construction, retail, fast food and delivery workers in Russia sending remittances back home to their families.

Atakeldiyeva, 23, is still looking for work in Kyrgyzstan. “A public school wanted to hire me, but everyone there thought I was a Russian spy,” she said.

Gulshat Uzenova is also out of work one month after she left St. Petersburg with her two children.

“My specialty is banking but they’re not hiring yet, even with my experience,” she told The Moscow Times. “There are difficulties everywhere.”

The mother of a disabled child who requested anonymity said she stopped looking for work in St. Petersburg after the start of the invasion and returned to Bishkek.

“Unemployment rose after the war and they were only hiring their own citizens,” she said.

“I wanted to stay as long as possible to see the results of my child’s treatment, but the doctors said there may be none and I opted to come back.”

The war-related exodus follows that of the tens of thousands of labor migrants who left Russia for Central Asia during the Covid-19 pandemic.

But for every returnee, many more have stayed in Russia, hoping to ride out the crisis. Uzenova said her husband stayed behind “in hope that things will get better.”

Atakeldiyeva was the only member of her family to leave Russia.

“My parents’ lives and work are there, they don’t know what to do here. They plan to return, but only after retirement,” she said, adding that her 11-year-old brother is in Russia studying at a military academy.

A number of citizens from Central Asian states have reportedly fought with the Russian army in Ukraine. While some of these men are naturalized Russian citizens, others were said to have volunteered as contractors in exchange for expedited citizenship or money.

Media reports suggest at least four Central Asian soldiers were killed in Ukraine, with evidence of funerals in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

The Kremlin-backed Federation of Migrants of Russia says labor migrants are not fleeing Russia en masse, despite the volatility of the Russian ruble and labor market as well as the waning appeal of a Russian passport.

Kyrgyz officials have also said they are unconcerned about a possible influx of migrants — although Economy Minister Daniyar Amangeldiev said last month that the country was in negotiations with South Korea and Turkey to ease visa restrictions for Kyrgyz labor migrants if there was a surge of returnees.

Less than half of Kyrgyz labor migrants in Moscow told a union survey in March that they were considering going home. Nearly all of them reported feeling the effects of economic difficulties on their day-to-day lives.

Uzenova, the banker, said a social media support group for Kyrgyz emigres in St. Petersburg that she co-moderates has seen no let-up in requests for help with jobs and accommodation.

“Most of them are waiting for things to improve, but there are also those who fly back home because of economic problems,” she said.

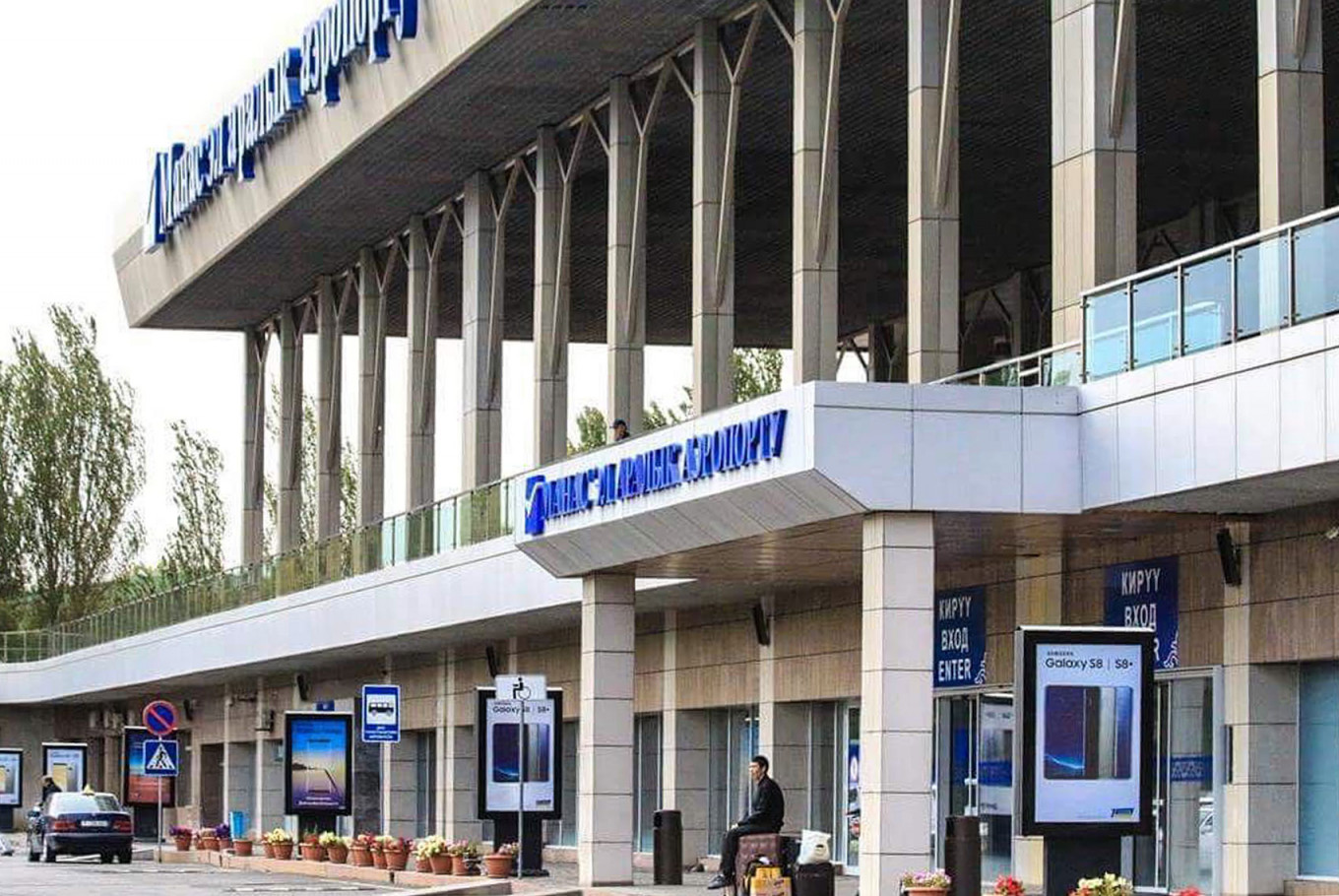

For some would-be returnees, rising flight prices have meant plans to go home have been put on hold. Kyrgyz travel agents said last month that demand for Moscow-Bishkek and St. Petersburg-Bishkek flights had risen fivefold since President Vladimir Putin ordered troops into Ukraine.

As labor migrants began returning to Central Asia, tens of thousands of Russians decided to flee their country over fears of political persecution, rumored border closures, conscription and a coming economic collapse.

Many bought tickets to Central Asian states.

“On our way back [to Kyrgyzstan], there were Russians escaping to Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan,” said the Kyrgyz mother who left with her disabled child.

Several Central Asian countries have recorded upticks in numbers of Russians crossing their borders since the beginning of the invasion. Local officials have said that as many as 130,000 Russians entered oil-rich Kazakhstan since the start of the invasion — double the amount in the same period last year.

Asked about Russians flocking to Kyrgyzstan to escape the war, all three Kyrgyz returnees interviewed by The Moscow Times welcomed the new arrivals.

“They’re just looking for shelter and a quiet life,” said Atakeldiyeva.

“Besides, it’s easier for them here, everything is much cheaper than in Russia and they don’t need to learn a new language.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.