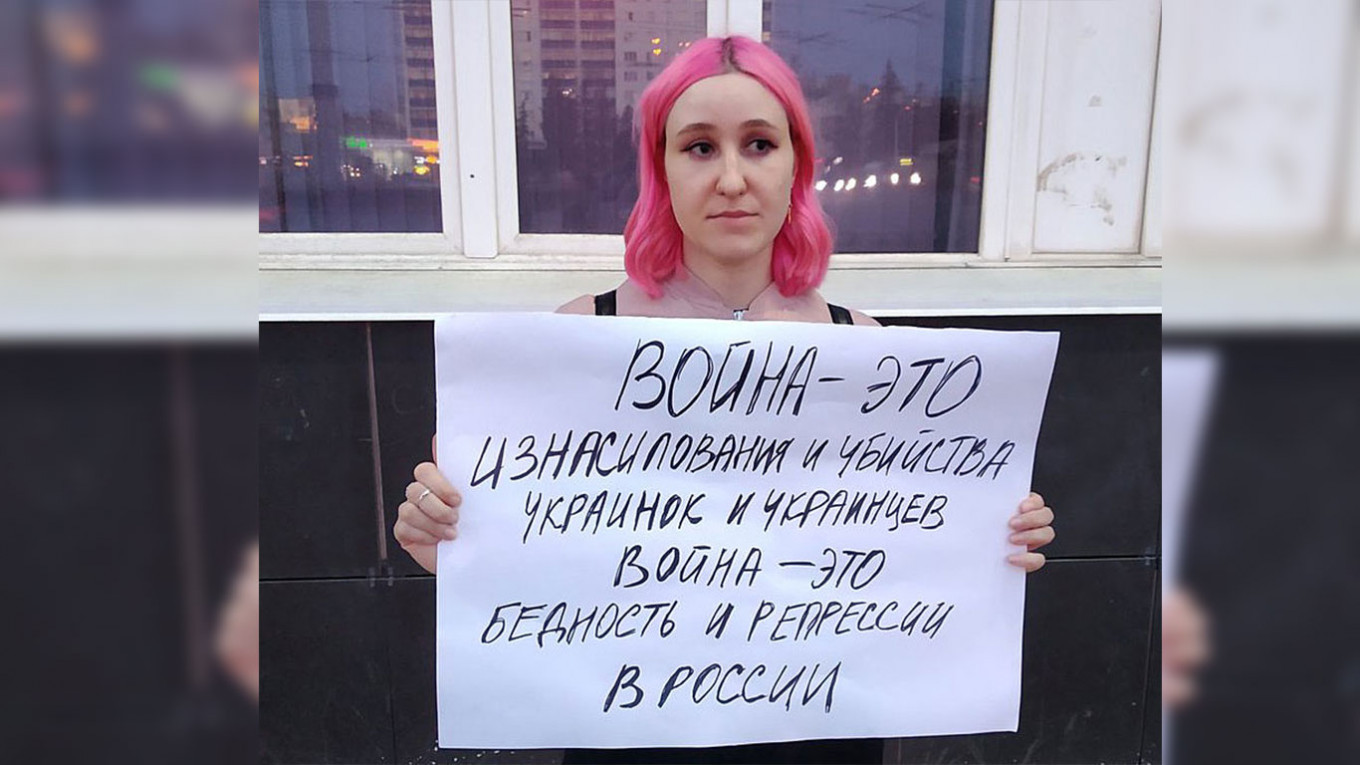

On April 19 a Bashkorostan court ordered journalist Daria Kucherenko to pay a 30,000-ruble fine (about $500) for her anti-war protest.

“After working eight years in journalism, during which time she monitored information in various media,” the court verdict stated, “she came to the opinion that people are dying in Ukraine from the actions of Russian servicemen and that Russian soldiers are raping Ukrainian women. Since she is a pacifist and feminist, she believes that it is in the traditions of Russian men to rape and beat women.”

Daria wrote on her Telegram channel that she completely agreed with this characterization. “Yes, I do believe that violence against women is a patriarchal Russian tradition. And that what we’re seeing in Ukraine is its consequence.”

I agree with Daria. The Philosophy Encyclopedia defines tradition as “an anonymous, spontaveously developed system of patterns and norms that a significant, consistent group of people follow in their behavior.” I don’t know which other countries have this tradition — although I suspect it exists in most of them — and that it is better in some places and worse in others. But that it exists in Russia I can say with certainty.

Today my social media is filled with posts that exclaim: "Who are all these men who rape women and children in Ukraine?" "It can't be!" "It's impossible to believe!" "Certainly not children!"

But just a few years ago, the same social media were filled with posts by women who took part in the flash mob "I'm not afraid to tell” and related their experiences with violence and harassment. In many cases, the stories were about their childhood.

My personal experience is typical. In high school, my girlfriends and I rode the subway with drawing pencil compasses in our pockets so we could defend ourselves from men who put their hands under our clothes. We also all knew the "man in the blue jacket" who would sit next to girls on the subway and pull his genitals out of his pants. As a teenager, I was terrified of a neighbor at our country house who told me, “Wow – you’re only 13 and you’ve got boobs like that already!” Around the same time, my dad's drinking buddy would open the door to my room and say, "I wish we had girls like you.”

An instructor on a camping trip would follow us to the river to see if he could see anything when we were washing up. When we'd sit on the floor, the teachers in the literature club would pull girls between their legs. When I was in the sixth grade, some high school students tried to force me into the apartment — I don't know what they had planned because I managed to get away. At 23, when I was returning home on a winter evening, a man attacked me from behind: He grabbed me by the throat with one hand and shoved the other between my legs. That time I managed to break free, too.

Literally all of my friends have almost the same experiences, and many women have experienced worse. In Serpukhov Margarita Gracheva’s husband cut her hands off. In St. Petersburg, Daria was shot in the eyes by her ex-partner with a shotgun.

Two-thirds of women murdered in Russia are victims of domestic violence.

According to a study by the Mikhailov and Partners Agency, when a woman says “no,” 47% of Russian men do not believe that means she doesn’t want sex. If the word "no" is not spoken, 39% of men consider it to be flirting and 7% consider it to be consenting to sexual intercourse — even if the woman actively resists. A survey by the Institute of Public Opinion "Anketolog" showed that 73% of Russians admit that violence by husbands against their wives is widespread in the country.

In the same poll, 14% of men said it is every husband's right to beat his wife.

"In Kaliningrad region a man got drunk and set fire to a house with his wife and children inside.” "A village deputy who stabbed his wife and dumped her body in a landfill in the woods was arrested near Krasnoyarsk.” "The body of Miss Kuzbass 2010 was found in Moscow; her husband said she had gone abroad." "In Chuvashia a jealous husband beheaded his wife with an axe and threw her head into an ice-hole." "In Yekaterinburg a woman said her husband beat her for several hours and threw her off their fourth-floor balcony." "In Transbaikalia a man strangled his wife and cat in front of his children." "In Pskov, a husband made his wife dig her own grave and bark like a dog under the table." “Chechens might have kidnapped a Chechen woman in Dagestan for an honor killing." "'She didn’t cover her head and even drank beer.’ Why male relatives kill women in the North Caucasus."

Those are all real Russian news headlines from 2021-2022.

In one poll, 14% of men said it is every husband's right to beat his wife.

After high-profile cases of violence or flash mobs like "I'm not afraid to tell," there is outrage on social media for a while, but nothing changes.

The state does not officially consider violence against women a "serious problem." That was how the Ministry of Justice responded to an ECHR request to Russia. "Legislation provides all the necessary tools," Peskov said in response to the ECHR's demand for a law against domestic violence in Russia.

The public does not consider the problem to be too serious either. Here’s just one example: After widespread coverage about Mikhail Skipsky, a teacher and game show player who molested his underage female students for years, parents continued to send their children to him for private lessons.

Denying that Russian men are capable of violence and brutality is the best way to keep it going. "They couldn't do that." "That can't be true." Unfortunately, it can be true. These people have been with us forever. What they do to Ukrainian women and children is truly almost impossible to believe, but the only difference is that in Ukraine they feel complete impunity. If they thought that they could get away with it here, they’d do the same to us.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.