When Russian reporter Lilia Yapparova began reporting from the Ukrainian side of Russia’s war on its post-Soviet neighbor, she expected to be met with hostility. Instead, people showed her kindness.

“I was honestly surprised by the fact people would spend so much time and effort to help me,” said Yapparova, who works for independent media outlet Meduza and has been in Ukraine since shortly after the beginning of the fighting. “People would have been well within their rights to say, ‘no, we have no time for you now.’”

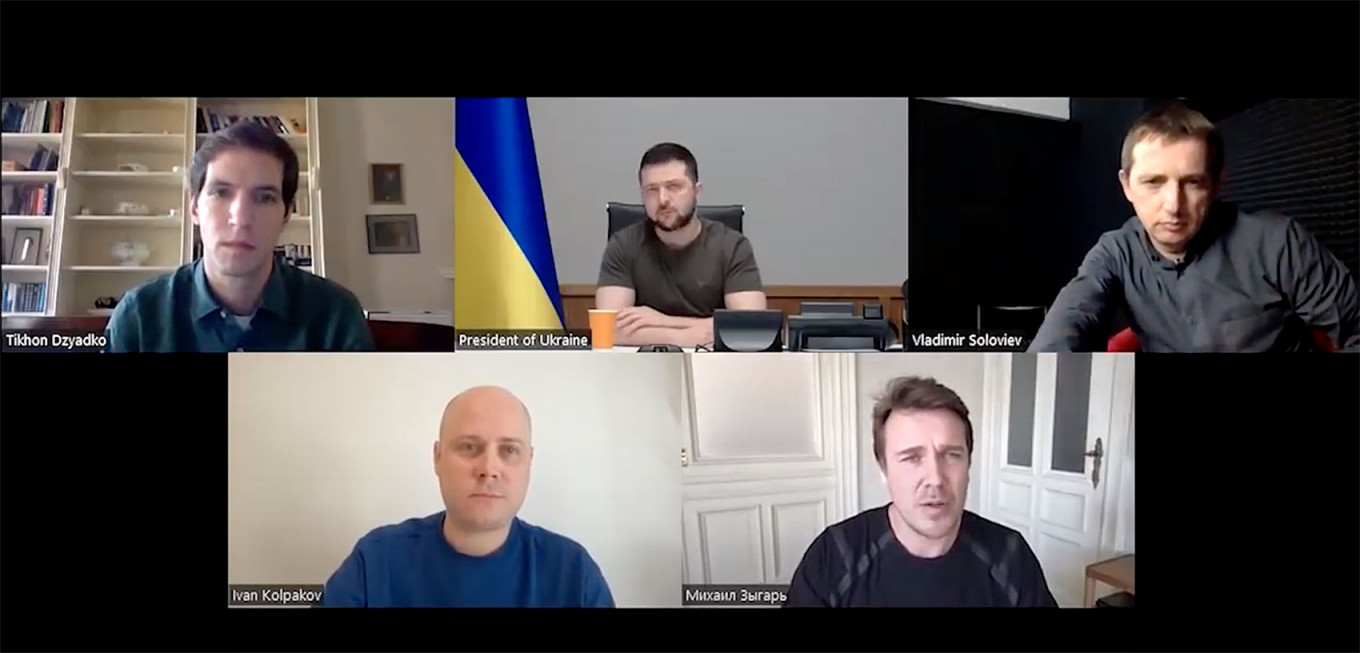

Despite a media crackdown back home, a handful of independent Russian journalists have been working tirelessly in Ukraine to report on the ongoing fighting. As well as interviewing Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, they have filed dispatches from battlefields in southern and northern Ukraine, and documented evidence of mass killings, rape and looting by the Russian army in towns and villages near Kyiv.

“People helped me,” said Elena Kostyuchenko, a reporter for newspaper Novaya Gazeta who arrived in Ukraine on the second day of the war. “There were the guys who carried my bulletproof vest and helmet for 25 kilometers. There were people who found me places to stay. And there were the people who helped my editors pass me money and medicine.”

As well as filing stories from the western city of Lviv, Kostyuchenko worked in the port city of Odesa and the badly-damaged town of Mykolaiv in southern Ukraine. Her most dangerous reporting trip involved crossing the frontline by car to reach the occupied city of Kherson.

But while journalists like Kostyuchenko were on assignment in Ukraine, the media outlets they worked for back in Russia were facing an uncertain future.

Kostyuchenko’s reporting was initially censored by her employer, Novaya Gazeta, who blacked out the word “war” in her articles to comply with Russian laws that could see her sentenced to 15 years in prison for spreading “fake news”. The newspaper also deleted some of Kostyuchenko’s stories from its website at the request of state communications regulator Roskomnadzor.

Eventually, Novaya Gazeta announced it was suspending its print and online operations until the end of the war.

Yapparova’s news outlet, Meduza, was blocked inside Russia shortly after the invasion, and now is only accessible with a VPN.

“Any urge to reflect on the popularity of my stories has been left in my pre-war life,” said Yapparova, who reported from the city of Chernihiv before it was surrounded by Russian troops, and from liberated villages near Kyiv, where she found evidence of looting, rape and summary executions carried out by Russian troops.

“I constantly think about the number of people in Russia who know the truth, and the number of people that are shielded from the truth. But I don’t think of it in terms of my work,” she said.

Despite growing censorship within Russia, talking to independent journalists is one of the few ways in which Ukrainian officials can try to communicate directly with a Russian audience that otherwise receives much of its news from state-owned media.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky gave a video interview to Russian journalists from outlets including Meduza last month, while Peter Verzilov, the publisher of independent news website Mediazona, met Zelensky last week to do an interview for a documentary film.

Those working on the ground for Russian media outlets are exposed to the same horrors and risks as Ukrainian and foreign war reporters.

“I visited a lot of morgues,” said Kostyuchenko. “In morgues, you can get objective information about the war. When I went to the morgue in Mykolaiv, I saw bodies stacked on top of each other. I opened a door to another room — more bodies, including children. In the shed outside, there were bodies too. And some bodies were just lying in the yard.”

Oksana Baulina, 42, a Russian journalist from the independent outlet The Insider died last month in Russian shelling while on an assignment to film damage in Kyiv’s Podil district. She is one of at least 20 journalists to be killed in the war, according to Ukrainian officials.

After more than a month in Ukraine, Yapparova describes her feelings as “a mix of physical, emotional and mental fatigue.” But she has no plans to leave the country.

“Along with the war against Ukraine, a war against the independent press [in Russia] is being waged. And I don’t know how it all will end. But I am not ready to bury the independent press in Russia. I will not do it,” she said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.