ROSTOV-ON-DON — If hundreds of thousands of refugees from Eastern Ukraine’s Donbas are about to descend on the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don, you can’t tell from looking.

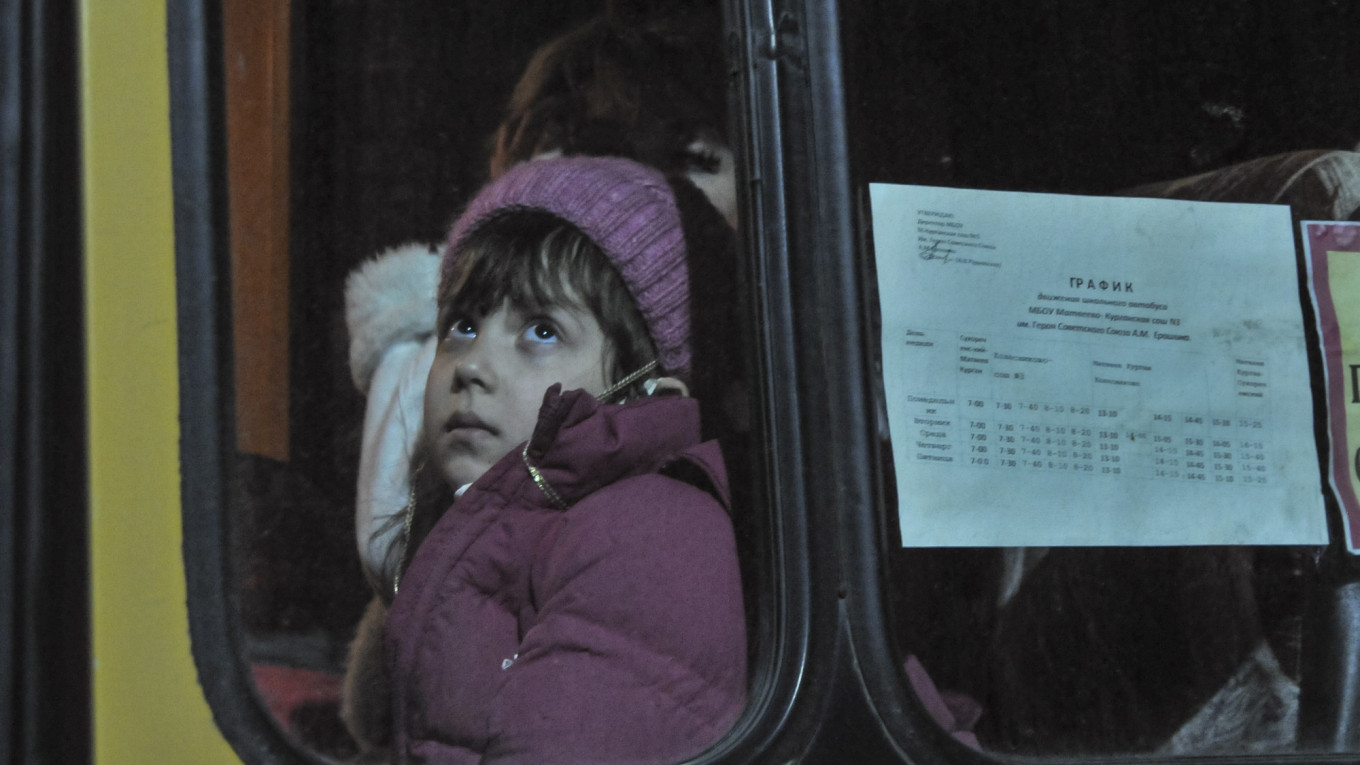

After authorities in the breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics on Friday ordered the evacuation of the elderly, women and children amid unsubstantiated claims that a Ukrainian attack is imminent, Rostov — the closest major Russian city to the region — should in theory be gearing up for an influx of people.

But despite local authorities declaring a state of emergency in Rostov, when The Moscow Times visited the southern city on Saturday, there was little evidence of war fever or refugees.

Though local media have reported that several thousand refugees have already been housed in camps in the nearby town of Taganrog, Rostov’s transport hubs were quiet, and few locals said they felt an escalation of Russia’s long-running conflict with Ukraine is around the corner.

“The main thing is that we don’t have a war,” said Kirill Noshaev, a 31-old barman, who was spending his weekend relaxing in a friend’s pub in downtown Rostov.

“But I don’t think we will. If something does happen, it’ll be limited in scale, like in 2014,” he added, referring to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent capturing of Donetsk and Luhansk by pro-Russian separatists backed by Russia.

Rostov is a historic port city straddling the estuary where the river Don pours into the Sea of Azov. Once known as a major center for organized crime, it has been linked to Russia’s war in Ukraine for the past eight years.

After being ousted during the Euromaidan revolution in Kyiv, ex-Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych fled to Rostov, triggering Russian intervention in Crimea and the Donbas.

The city’s location only an hour’s drive from the border with Ukraine, later made Rostov a key rallying point for pro-Russian insurgents in the neighboring Donbas.

On Saturday, local authorities said several shells fired on the frontline over the border landed in the Rostov region, underlining its position at the forefront of the conflict.

In the eight years since the outbreak of hostilities, the city has also become a center for refugees from the Donbas, which suffered economic collapse after the proclamation of the pro-Russian People’s Republics in spring 2014.

On Rostov’s streets, where restored Tsarist-era buildings jostle for space with infrastructure renovated for the 2018 football world cup — for which Rostov was a host city — cars bearing plates with the black-blue-red tricolor of the Donetsk People’s Republic are a common sight.

Many locals speak with a distinctive southern Russian accent, which has a strong Ukrainian influence.

But even as many in Rostov maintain family ties and political sympathies with those over the border in Eastern Ukraine, not all locals relish the role their city has come to play in the power struggle.

“Of course, people here do read the news, and hope that there won’t be a war,” said catering worker Anastasia, 23, who declined to give her last name.

“But there is a bit of anger about these payments,” she said, referring to 10,000 ruble ($130) payouts being offered to refugees arriving from the Donbas.

“This is our tax money.”

Lack of urgency

The lack of urgency in Rostov is reflected over the border in the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics.

Though separatist authorities have announced plans to evacuate almost a million residents of the Donbas, that would likely require a months-long effort, and only a few tens of thousands have been transferred over the border during the first two days of evacuation.

Even after the separatists ordered evacuation on Friday, several residents of the breakaway regions told The Moscow Times that they and their relatives were staying put, regardless of dire warnings from the local authorities.

“Everything’s okay here so far,” said Kirill Marnitskevich, an 18-year-old resident of Makeevka in the Donetsk People’s Republic who plans to enlist in the breakaway state’s army.

Though Marnitskevich cannot leave Donetsk under the terms of a mobilization order issued by the unrecognized government, he said his grandmother was refusing evacuation, and waiting for the situation to become clearer.

“She’s gathered her things, if something happens she’ll go,” he said in a telephone interview.

“We’ll see what happens.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.