ST. PETERSBURG — When Charlotte Wrigley went to the clinic at St. Petersburg’s UFMC migration center for a range of mandatory health checks for foreigners working in Russia, she didn’t expect to have to undergo a full gynecological examination.

“They told me I had to have a [Pap] smear test for syphilis, which is just not the way you test for syphilis,” the 34-year-old post-doctoral researcher told The Moscow Times, describing it as a “horrific experience.”

Since Russia introduced the compulsory tests for infections and addictions late last year, expats in Moscow have been voicing confusion over the frequency of testing and location of test sites, as well as reporting long queues and complicated bureaucracy.

Now foreign workers in St. Petersburg are reporting having to undergo gynecological and genitourinary tests.

Russia’s Health Ministry declined to comment on whether genital examinations are necessary under the new rules, while a UFMC employee who wished to remain anonymous said they were not aware of the need for physical examinations and that only blood and urine tests were necessary for HIV and syphilis.

None of the foreigners The Moscow Times contacted in Russia's capital Moscow said they had to have physical checks.

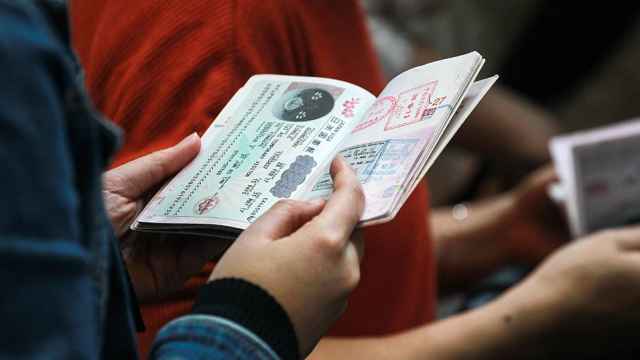

All foreigners over the age of six who arrived Russia on or after Dec. 29, 2021, who are staying in the country for more than three months — excluding those with residency, diplomats, members of intergovernmental organizations and their families — are required by law to test within 30 days of arrival for HIV, drug addiction, Covid-19 and psychological health, as well as a number of sexually transmitted diseases.

A dermatological exam, X-ray for tuberculosis and the collection of biometric data should also be carried out as part of the process. All tests must be taken in addition to any pre-arrival visa requirements such as an HIV certificate.

Jennifer Richardson, 27, a part-time English teacher and student who went to St. Petersburg’s migration center, said she was told she could be deported if she didn’t have a gynecological examination as part of the set of tests.

“You see the chair with the stirrups up and it’s like, ‘Oh, take all your clothes off and show us your vagina’ … I don’t know exactly what they [were] looking for. No idea. I should have asked, but I didn’t really think about it at the time,” she said.

Both Wrigley and Richardson said that the authorities did not provide English translations nor explain all of the tests and documentation.

While tests in the Moscow region are currently only possible in the clinic at the Sakharovo migration center 80 kilometers outside the city, private clinic groups Medsi, Meditsina and the European Medical Center are waiting for approval to be able to offer them. In St. Petersburg, there are several clinics for testing outlined on a government list. Fingerprinting options besides Sakharovo in Moscow are available, but usually by appointment only.

Costs range from around 4,200 to 6,600 rubles ($55-$87) depending on the region and whether the foreigner opts to translate their passport privately.

At present, the law states that the tests must be repeated every three months, although two officials overseeing the process at St. Petersburg’s UFMC said tentatively that they are awaiting further instructions. A statement on the Health Ministry’s official site indicates that the tests will not have to be so frequent in future.

While the extent of sexual health examinations represents the most significant variation between the cities, there have also been discrepancies in whether dermatological examinations are carried out, how thoroughly Covid-19 tests have been taken, and which questions, if any, psychologists have asked foreign workers during the process.

Expats in Moscow spoke of testing that was less extensive and reasonably well-organized, but reported perfunctory questioning and chaotic queues.

One British Moscow-based professional who asked for his name to be withheld said the psychologist didn’t ask him any questions at all, preferring to chat for a few minutes — which annoyed him given the costs of the tests.

This professional said he tried to keep a “zen” mentality toward the testing and bureaucracy and “to treat the whole thing like a joke, and not a huge waste of money.”

He added that if the tests are to continue every three months as the law currently states, he would consider leaving Russia to find work elsewhere.

This sentiment was echoed by longtime Moscow resident Martin, a 39-year-old English teacher who asked for his surname to be withheld, who said he had to make four trips to Sakharovo to complete the tests and biometrics correctly and collect results.

He said that while the administrative process was generally smooth and the staff polite, the queue was volatile because the ticketing machine kept ejecting its supply at random intervals.

“I saw lots of fights in the queues, people kicking each other … Every hour there was a different fight.”

Martin was keen to stress that, despite the fraught tempers, everything followed some sort of order.

“The system kind of works okay … just at the inconvenience of the people undergoing it.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.