In summer 2021, Dmitry Politov realized he had to join the growing band of allies of jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny fleeing Russia amid an escalating crackdown on dissent.

But Politov — who had heard tales of Russian agents harassing, and even assassinating emigres in Europe — decided against joining burgeoning exile communities in Lithuania and Georgia, and set his sights further afield.

“I wanted to go to America,” Politov, a bearded, 29-year-old Muscovite who speaks in short, clipped sentences, told The Moscow Times in an interview.

“It’s safer. In Europe, there are well-known cases of people being poisoned or murdered.”

With the U.S. Embassy in Moscow shutting down consular services amid mass diplomatic expulsions, and tourist visas elsewhere hard to come by under pandemic restrictions, Politov was forced to take extreme measures. On Aug. 9, 2021, two months to the day after Navalny’s organizations were banned as “extremist” by a Moscow court, he boarded a charter flight to the Mexican resort city of Cancun.

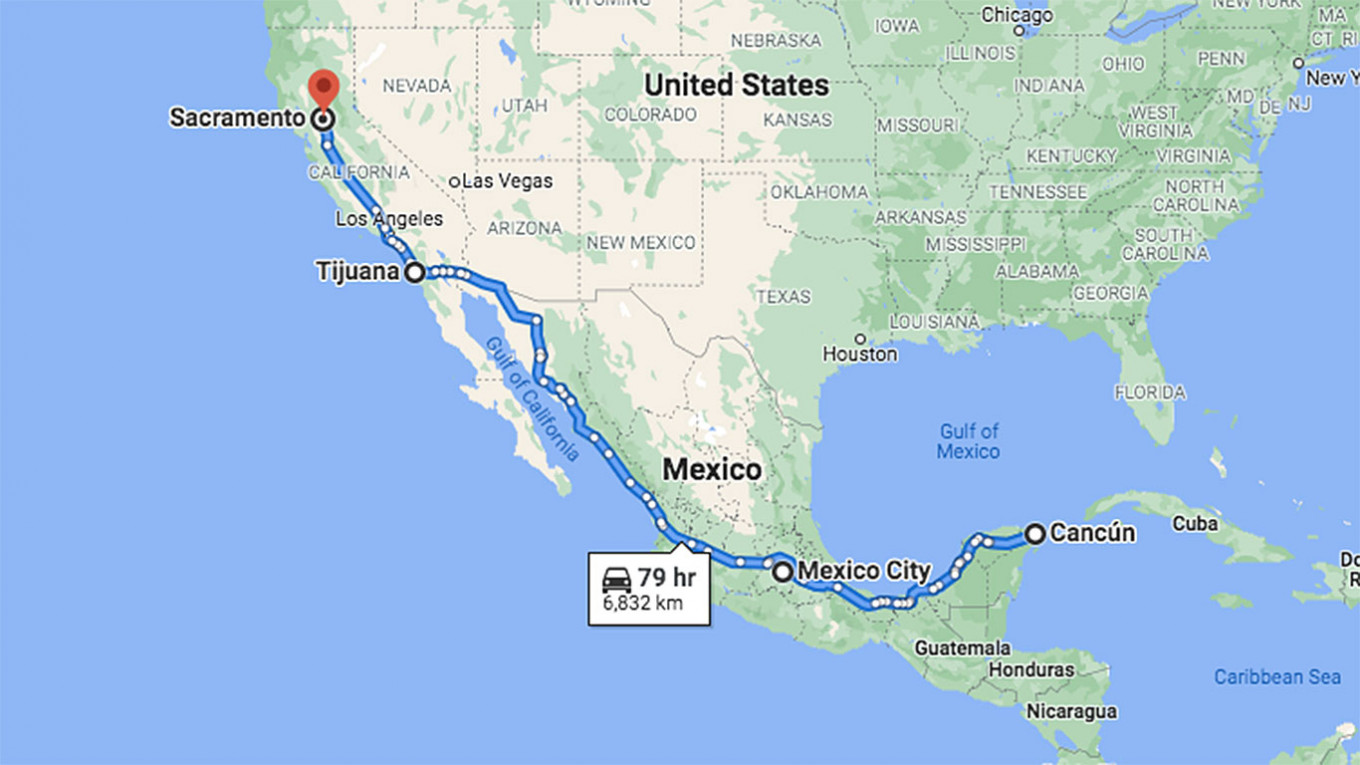

In a video diary filmed in Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport departures lounge, Politov laid out the plan: Cancel his return flight, slip out of Cancun and make for the frontier city of Tijuana, almost 3,000 miles away. Once there, he’d cross the border into California and claim political asylum in the United States.

Politov had set out on one of the last available routes into the U.S. for Russian immigrants, one that is fraught with unforeseen dangers, unscrupulous middlemen and fake asylum claims.

The Moscow Times interviewed asylum seekers — some legitimate and some seeking to play the system — who have entered the U.S. via Mexico, and the shady operatives who charge big fees to help them, to cast light on a backdoor into America that is surging in popularity among Russians looking for a better life.

Before the pandemic, the rules for Russians hoping to immigrate to or claim asylum in the U.S. were simple.

Back then, Russians persecuted at home, whether as political dissidents or as members of repressed religious groups like the Jehovah’s Witnesses, could come to America on tourist or student visas and claim asylum while already in the country.

But the recent wave of emigration — prompted by the Kremlin’s crackdown on political opposition, civil society and independent media — has coincided with an almost total shutdown of Russians’ route to America.

First, the pandemic saw U.S. embassies worldwide closed, and a slump in the number of tourist visas issued.

More recently, poor relations between the U.S. and Russia forced the American Embassy in Moscow to halt visa services for Russians, as mass diplomatic expulsions and a ban on hiring local employees resulted in skeleton staffing.

With the legal door to America effectively closed, Russians have joined the Central Americans, Haitians and Cubans who have traditionally made use of the Mexican border route to the U.S.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 4,103 Russian citizens were detained at the border in the year to October 2021, a tenfold increase on the year before. In one December incident, border patrol officers fired shots at vehicles carrying Russian migrants across the border.

For Yekaterina Mouratova, a Miami-based Russian-American immigration lawyer whose firm provides legal representation for Russian-speaking asylum seekers detained at the southern border, the surge in numbers is the result of a perfect storm of factors, both in the U.S. and abroad.

“Most of all, this is about the deteriorating political situation in many post-Soviet countries,” said Mouratova, who singled out Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan — all of which have seen recent political unrest and repression — as particularly well-represented among migrants attempting to cross the border.

According to Mouratova, policy changes in the U.S. itself — where the Biden administration has eased Donald Trump’s harsh border policies — have also removed a major deterrent for would-be migrants.

“A lot changed when Joe Biden entered the White House,” she said. “People understand that now it’s easier to get asylum on the border than it was before.”

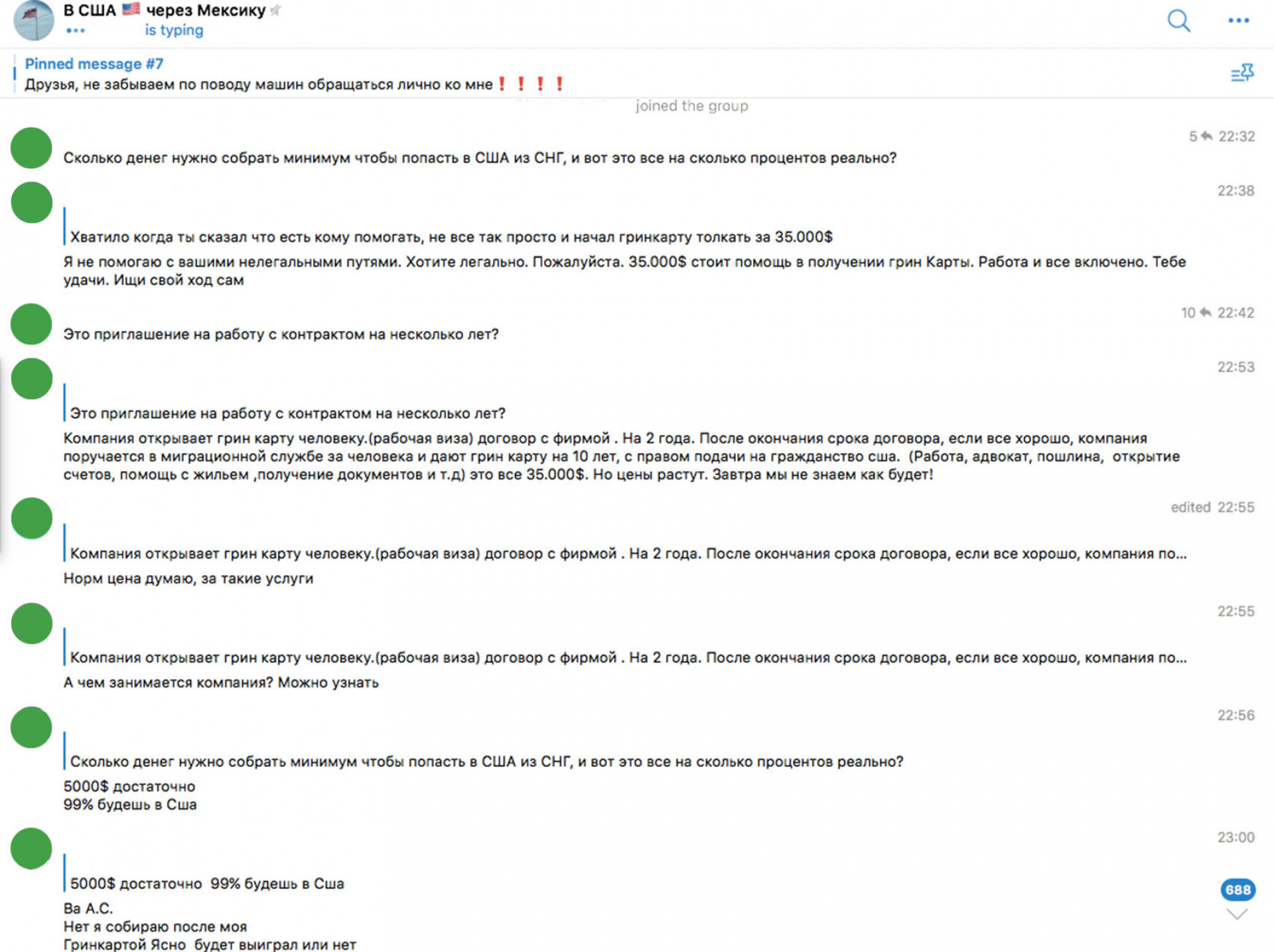

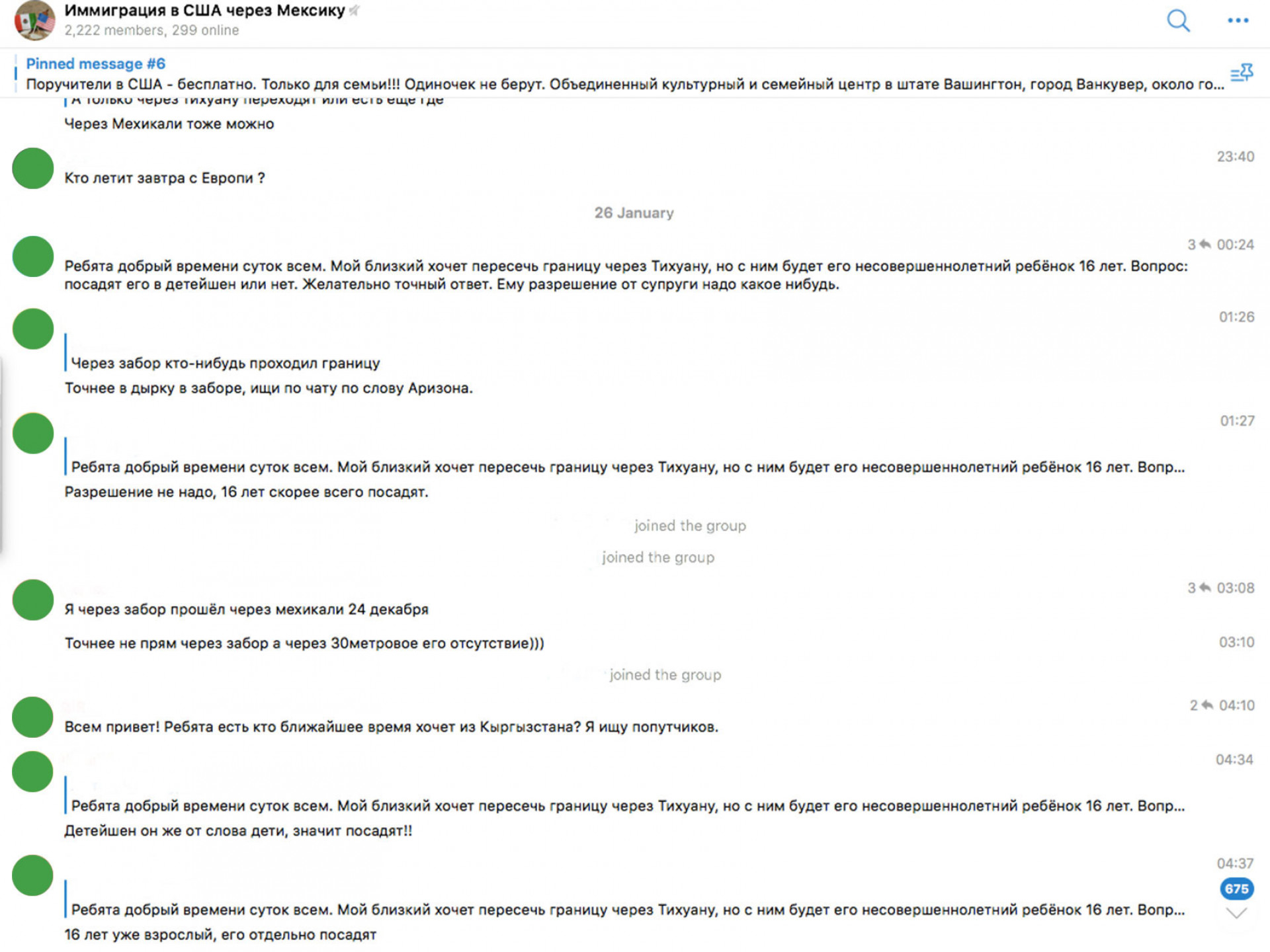

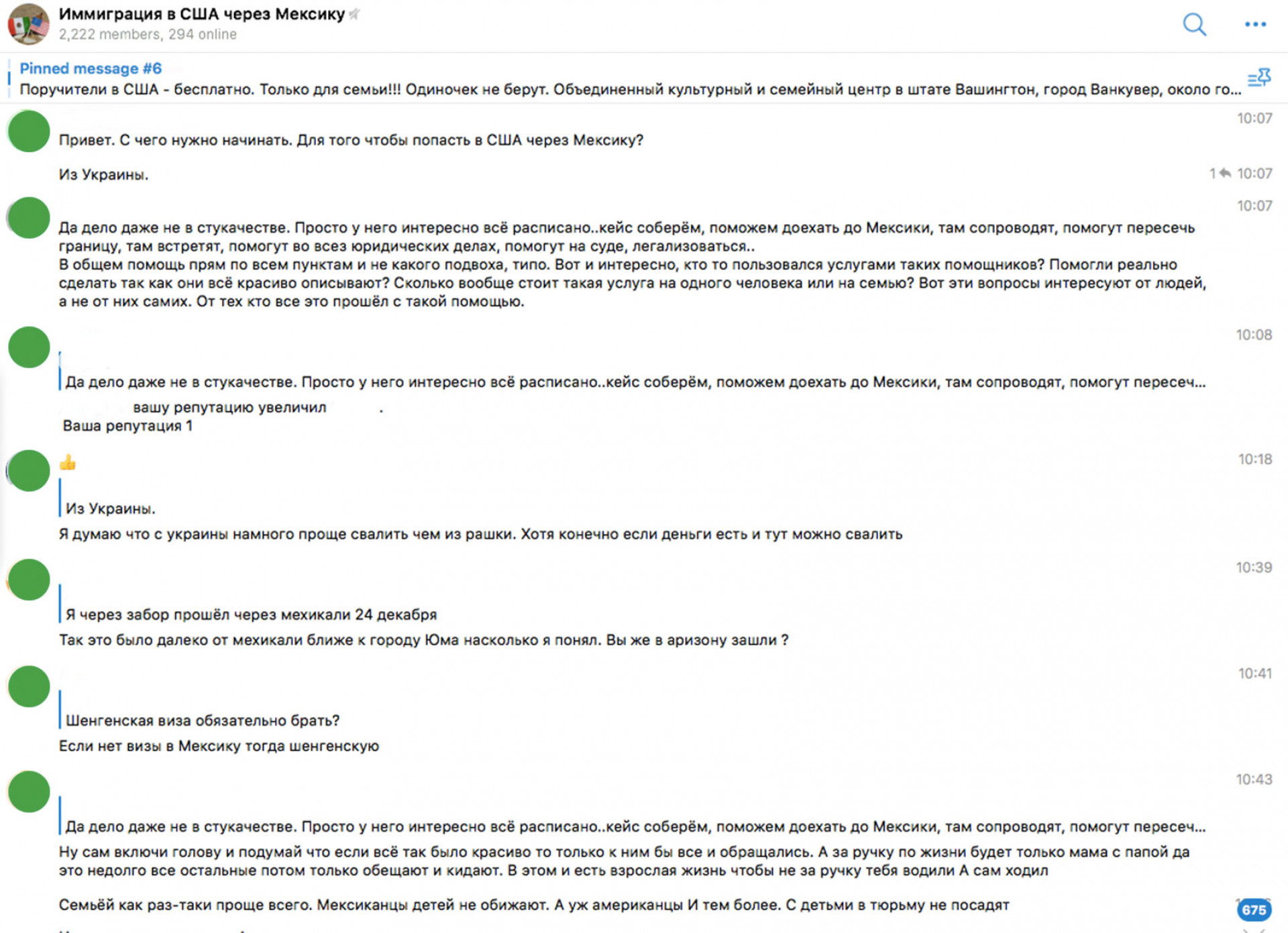

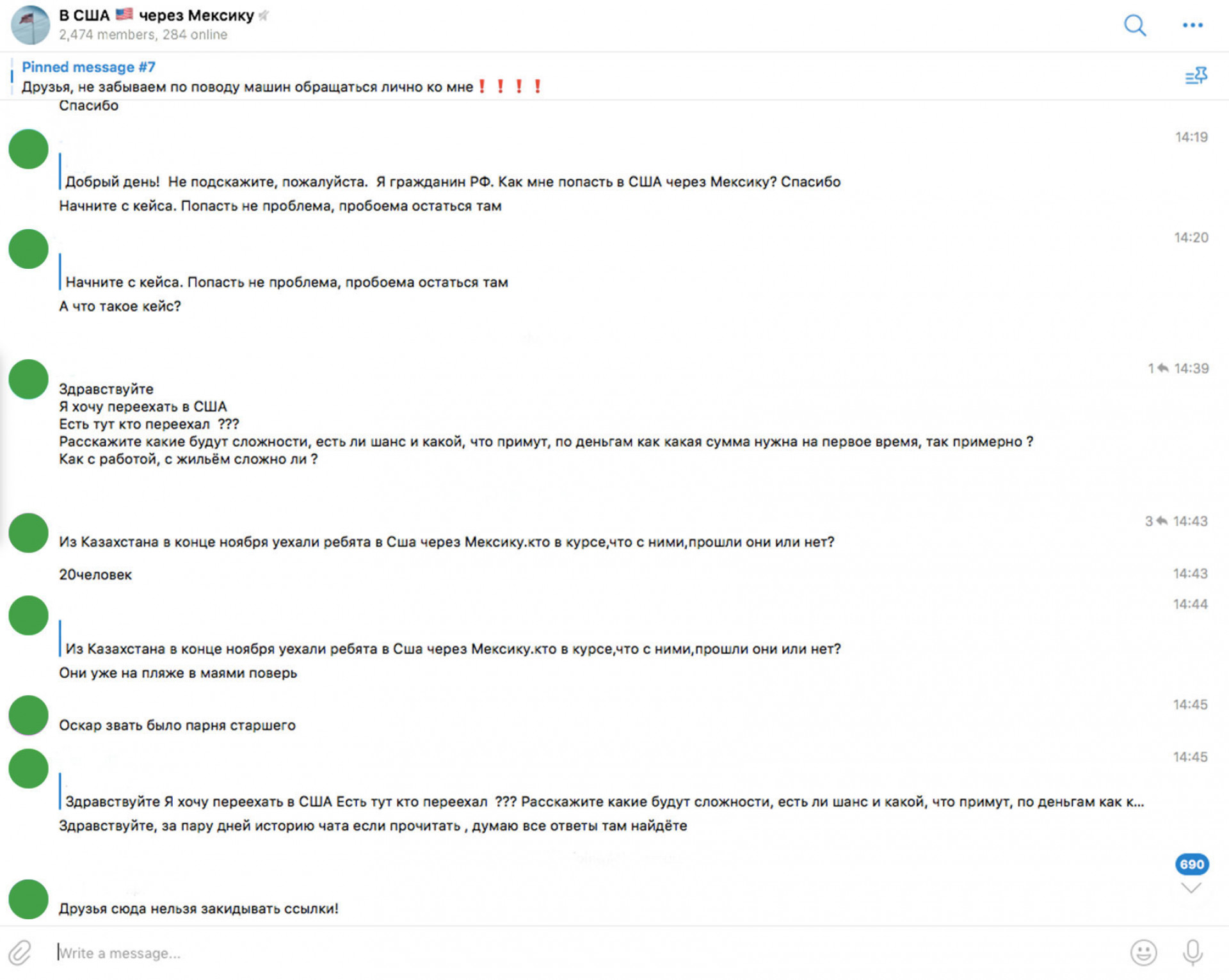

On Facebook and the encrypted messenger service Telegram, thousands-strong groups dedicated to U.S. border crossings have sprung up, often run by shadowy immigration brokers who charge would-be immigrants large fees for border-crossing packages.

Contacted over Telegram, Vladimir, a Russia-based immigration broker who declined to give his surname, explained his business to The Moscow Times.

“You pay $2,500 for the full package. You pay for the Mexican visa, we meet you at the airport in Mexico and drive you across the border.” “We take about 10-12 people [at a time]. It always works, the border isn’t hard to cross. It's so large.”

Clandestine mission

For Russian-speaking migrants attempting to cross the border with or without brokers’ help, the Mexico route can often resemble a clandestine mission.

Though Cancun is a popular resort for Russians, the Mexican authorities — who have agreements with the U.S. to turn back would-be border crossers — have begun refusing entry at the city’s airport to Russian citizens they suspect of being migrants.

Successful migrants told The Moscow Times they had taken elaborate precautions to avoid suspicion, including avoiding flying into Cancun from Moscow and Frankfurt, connecting hubs for Russian travelers.

Once in Mexico, like many of his compatriots Politov avoided flying direct from Cancun to Tijuana, a frontier city separated from neighboring San Diego, California by little but a fortified border fence, to avoid arousing suspicion.

Traveling to Tijuana after a layover in Mexico City, he hired a pair of Mexican fixers, paying them $1,200 for help crossing to California. It’s a decision he now regrets.

“All they do is give you a car, and tell you what direction the border is in,” he said.

A first attempt to reach the U.S. side of the border, where migrants are theoretically entitled to claim asylum, failed when an American border guard turned Politov back to Mexico and he spent two nights in jail.

“I found out that a lot depends on the person you meet there,” said Politov.

The good life

While the Mexico route is heavily used by refugees fleeing political or religious persecution in Russia, some would-be migrants are set on using the asylum system for their own ends.

For Anastasia, a hairdresser from a large city on the Volga river, who declined to give her full name, America represented a fresh start.

“I decided to leave because my life was kind of not going anywhere,” she said in a telephone interview.

“When you watch TV, you can always see how good life could be in America,” she added.

Having tracked down an immigration broker through Russia’s Facebook equivalent VKontakte, Anastasia paid $2,500 for the trip through Mexico. Arriving on the border, she applied for political asylum using a false story written for her by the broker.

“We told them my family and I are persecuted because we don’t like the authorities,” she said.

“I am not sure if what I did was cheating,” she said. “I think it's unfair that I can’t travel to America freely in the first place.”

When migrants reach America, they must submit a detailed application laying out their reasons for claiming asylum.

Including a questionnaire explaining the migrant’s reasons for fleeing their home, proof of any personal history of persecution, and information on the wider state of human rights in their country of origin, the package is referred to by Russian-speaking migrants as a “case.”

Vladimir, the immigration broker contacted by The Moscow Times, said that a pre-written asylum case costs an additional $500.

“We come up with cases all the time,” he said. “It's really easy, you just have to use your imagination.”

“We can write that you are being threatened due to your political views, or that you are a Jehovah’s Witness, or that you don’t want to serve in the army … All cases are custom-made and unique.”

The Moscow Times has obtained what appears to be a U.S. asylum application, pre-written by a broker for Belarusian citizens fleeing political persecution, with only specific personal information left blank, possibly pending payment.

Asylum journey

For those who make it over the border into the United States, their asylum journey is only beginning.

Asylum seekers are detained on arrival in the U.S., where they must pass an initial screening interview with a border agent. Those who get through are released from detention after two or three days, after which they have a year to submit documents proving their right to asylum to an immigration judge.

For Politov, who made it across the border on his second attempt after teaming up with a group of fellow refugee Navalny supporters, the elation of having made it to America is tempered by the challenges of life in a new country.

Like most of the asylum seekers interviewed by The Moscow Times, he ended up in California’s state capital Sacramento, which has a large Russian-speaking immigrant community.

Asylum seekers are forbidden to work until an immigration judge has confirmed their status, and must rely on savings or support from friends and family in the meantime.

“It’s kind of an unclear part of the law here,” Politov, who is working on mastering English, answered when asked how he was supporting himself in America.

But despite the difficulties, Politov — whose Navalny links mean his asylum case is likely watertight — is looking forward to having his permanent immigration status confirmed, and eventually applying for a Green Card U.S. residency permit.

“I won’t go back to Russia until the regime falls,” he said.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.