The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts has been having something of a women’s moment recently. The groundbreaking exhibition “Muses of Montparnasse” — a show of women artists living in Paris in the early 20th century — had not yet ended when another show of work by a woman artist opened. The show of works by the Austrian artist Xenia Hausner, called “True Lies,” is on display on the third floor or the American and European building of the museum complex.

Hausner was introduced by Pushkin Museum director Marina Loshak as “a big artist,” and indeed almost everything about her art is big: big canvases, big figures, big brush strokes, big colors, and big themes.

The child of the renowned painter Rudolph Hausner, she studied stage design in Vienna and London. In the late 1970s Hausner embarked on an illustrious career designing sets for theater, film, and opera in all the theatrical capitals of Europe. In the early 1990s she began to concentrate on painting.

She soon settled on one of the attributes that define her work — their large size. “I just started painting,” she told The Moscow Times, “and the first paintings were already larger than life, but not that much [larger], and then they grew a little bit. Now I think I've found the scale that I like to work with.”

And she found her preferred subjects — women: “When I reflect on it, I think women are more complex. They have to know more, they are multitasking. They are maybe contradictory or they're more complicated… [which] makes them more interesting for art. This is how I rationalize it. But it was my spontaneous approach. My universe is females. And in this female universe, I cast all the parts with women —sometimes men, too, but more women.”

And she invented her own genre of storytelling — staging scenes in her studio with models, photographing them, and then putting the story on canvases, sometimes using mixed media. Her canvases seem to tell stories, but the stories change as she paints. “I do not know the end of it…. I have a vague idea how it's going to work or what it should be, but I do not really know exactly… There are moments when the painting changes my direction or changes my original idea.”

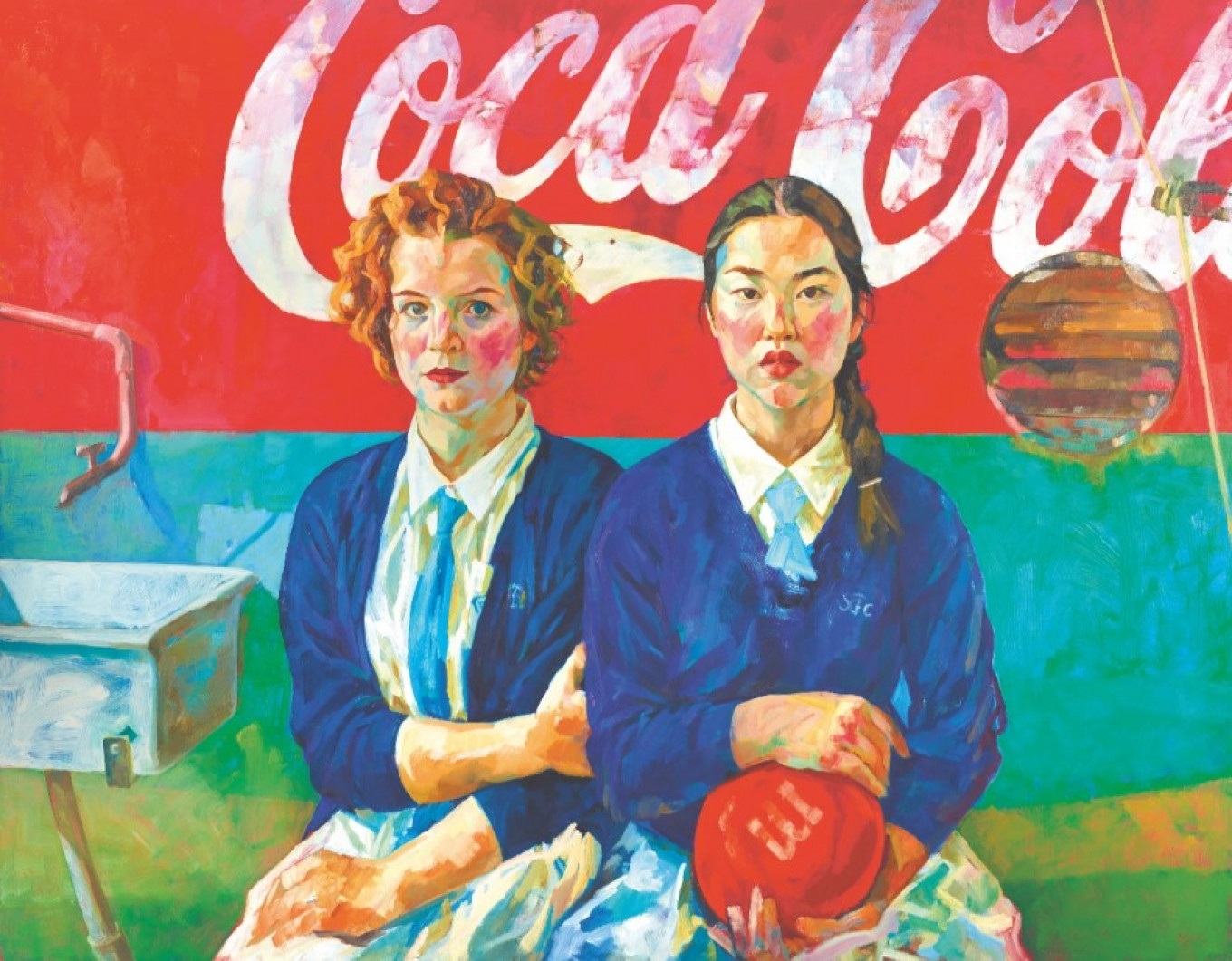

Hausner’s paintings show travelers, lovers, exiles, people in trouble or in difficult circumstances, a mix of cultures, and ambiguous but intense relationships among people. Her subjects usually don’t talk among themselves, although there appears to be intense relationship. They are often sitting or standing and facing the viewer, sometimes staring straight out of the canvas with a gaze that is bold but unreadable — or perhaps ambiguous — or maybe open to interpretation.

For example, in a canvas called “Hot Wire,” the viewers seem to be looking at the scene from a television or a piece of furniture with wires running through it. We are looking at a woman in a red dress, who is lying on a couch and staring back at us (or the television? or something else?). Another woman leans down to her as if asking her a question or speaking to her. The red-dress woman appears not to respond. Is she caught up in a television show? Is the other woman her mother or sister or lover? Are they fighting? Is the red-dress woman bored or angry or just not interested? Who knows? It’s whatever you think it is.

These are Hausner’s “true lies” — the truth is the story that each viewer sees and invents, but that truth is at its heart a lie: what we are seeing is not “real” – it was staged with models in the artist’s studio. But it doesn’t matter — what we see is our truth.

A stairway to other worlds

The show at the Pushkin Museum begins at the top of the long staircase to the third floor. When you reach the top, you are greeted by a painting of two women called “Disobedience.”

The first painting in the first room is the artist sitting at a table in front of a festive object, perhaps a cake or a present. She is holding a gun to her head. In another painting she stands nude, arms akimbo, behind her worktable scattered with paints. Nearby in another painting the artist seems to be hugging someone in farewell (“Winter Journey”), her strong painter’s arms and hands on the man’s frail back.

It is a powerful start to the show.

And then you walk among photographs and enormous canvases filled with brightly colored, vivid people: groups of women or women and men on couches in houses, on the street, on trains. In “Blind Date” a young blond man looks out from behind the back of a laughing young woman toward another woman, who is older and has her black-gloved hand over her eyes. They appear European, but there is foreign script on the wall — bus? poster? store? — behind them.

There are schoolgirl friends, blurred in happy motion, and halls of exiles: people of various ages and nationalities, men and women, leaving on trains in desperation or sorrow or relief, posing in their new homes (perhaps), saved from a shipwreck (maybe) or living in a shipping crate as seen from above (certainly).

As you look at her works, the realist painter Ilya Repin comes to mind with his narrative canvas of “They Didn’t Expect Him,” or his enormous painting with untraditional perspectives of officials in “Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901.” There is something slightly reminiscent of Russian avant-garde painters in her portraits, and her use of cultural markers like Coca Cola brings to mind Sots Art and other late Soviet and early post-Soviet art. And her bright, vivid palette and brilliant use of color? Abram Arkhipov would have welcomed her into the fold.

One of the visitors to the exhibition, who just identified herself as “an art lover,” said she’d seen the show three times. “I keep coming back because the images are so strong, I want to look again and see if this time I see something different. They are very strange, but very familiar, too,” she said.

Hausner said she wanted each person to come away with their own stories. “This is just what I want. You think about it, and you kind of interpret it with your own life and with your possibilities, with your experiences,” she said.

“I would also say: Look at the painting,” she continued. “I’m very simple. I just love paint and I love to paint. So just enjoy the painting.”

And that’s what the art lover did. “I just love them,” she said.

The show, held in cooperation with The Albertina Museum Vienna and with support of the Austrian Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, Civil Service and Sport, runs through Jan. 16.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.