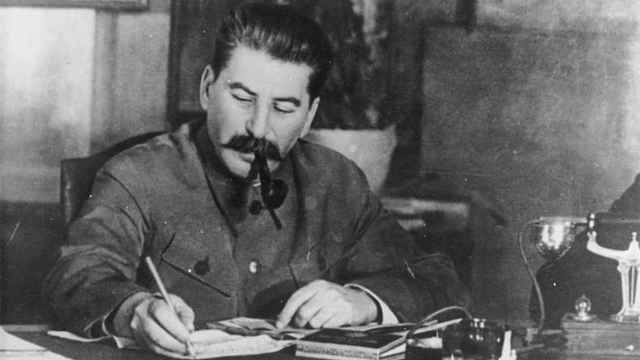

VLADIKAVKAZ, North Ossetia - On a remote mountain roadside, not far from a flashy ski resort, narrowed eyes on a stencil of the Soviet Union’s most notorious tyrant stare impassively out of the rockface. His head and shoulders, generously whiskered and draped in medals and gold piping, loom four meters high, dominating the pass below.

Tabooed since his 1956 posthumous denunciation by successor Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin is once again a familiar sight in the deserted valleys and soaring peaks of this corner of Russia’s North Caucasus.

But although recent years have seen the dictator’s reputation improve across Russia, North Ossetia — a region of 700,000 on the country’s southernmost flank — takes things to a pro-Stalin extreme.

The tiny autonomous republic has around thirty public monuments to Stalin — more than any other Russian region — while his portrait is a common sight in homes and businesses.

“In Ossetia, everyone has their own Stalin,” said Indira Gabolayeva, a prominent local activist affiliated with the Communists of Russia, a small, hardline Stalinist political party.

“For some, he’s one of the main theorists of Marxism-Leninism. For others, he’s an effective manager, or just the one who won the war.”

“Too bad Stalin isn’t around anymore”

In North Ossetia, a peripheral region which saw some of Russia’s worst economic decline and ethnic conflict after the fall of the U.S.S.R., memories of Soviet industrialization, educational and social welfare programs have become tinged with nostalgia.

Even Stalin’s brutal leadership is seen as a lost era of order, according to Gabolayeva.

“If someone has a fight with their neighbor, they’ll often say ‘Too bad Stalin isn’t around anymore!’ For some reason, they think he’d have made sure the neighbor was punished,” she said.

It’s a story with echoes across the country. Though the Kremlin has never fully rehabilitated Stalin after his denunciation, in recent years it has preferred to stress what it sees as his successful record of wartime leadership, industrial progress and foreign policy achievements. Meanwhile, the millions killed in the purges, show trials and famines over which Stalin presided have been played down.

Historical revisionism in the Kremlin has been echoed in wider society. A June 2021 poll by the independent Levada Center pollster showed a majority of Russians taking a positive view of Stalin.

Another survey, taken in May last year, showed support for Stalin monuments trending upwards, with 48% of Russians backing their installation and only 20% opposed.

However, in Ossetia, Stalin’s memory also benefits from a warm, if historically dubious, sense of hometown loyalty.

Ossetians widely believe that Stalin — born Josef Dzhugashvili in 1878 in Gori, then an ethnically mixed city in modern-day Georgia on the fringes of unrecognized South Ossetia, was one of their own.

Stalin’s characteristically Georgian surname, Ossetians insist, is a Georgianized form of Dzhugaev, a common Ossetian family name.

Though there is no evidence that Stalin, whose first language was Georgian, ever identified as an Ossetian or spoke the language, Western and Russian historians have acknowledged that Stalin’s father, shoemaker Besarion Dzhugashvili, may have had some Ossetian roots.

In Tskhinvali, the capital of South Ossetia, a self-proclaimed state that most of the world recognizes as part of Georgia and where Stalin’s purportedly Ossetian ancestors are said to have originated, authorities in 2020 restored the city’s Soviet-era name, Stalinir, for ceremonial uses.

Stalin Street, the city’s main drag, is one of a bare handful of roads to have regained a name once widespread in the communist bloc.

Either side of the border, Stalin’s visage is a common sight in Ossetian households, often displayed alongside revered national poet Kosta Khetagurov.

Widespread devotion to Stalin has also seen North Ossetia become a stronghold of the so-called “Soviet Citizens”, a conspiracy theory movement that believes the U.S.S.R. still legally exists and that post-Soviet Russia is an illegitimate usurper.

“Ossetians are a very close-knit people,” said activist Gabolayeva.

“If one of us achieves fame and glory then the nation will give them their due recognition.”

Stalin’s following in North Ossetia has even helped foster a rare export industry in what is one of Russia’s poorest regions.

For some years now, local artists have been some of the most prolific producers of Stalin monuments erected throughout Russia and the former U.S.S.R.

In 2019, the 140th anniversary of the dictator’s officially recorded birthday — celebrated in North Ossetia with a concert and folk dancing — brought with it a wave of new Stalin statues across Russia, many of them the work of Ossetian craftsmen.

In the workshops of the North Ossetian Artists’ Union in Vladikavkaz, the region’s capital, Stalin paraphernalia is big business, with busts, statues and even death masks of the dictator for sale.

Though most of the Stalin busts produced here are lightweight, mass-produced affairs, molded from clay, finished with a coat of bronze-colored paint, and barely larger than a clenched fist, occasionally a weightier order comes in.

Sculptor Ibragim Khayev, 42, has spent much of the last year working on his latest Stalin, a full-body, uniformed statue of the Generalissimus which stands at almost twice Khayev’s own height.

Commissioned by the Ossetian head coach of Russia’s freestyle wrestling squad, Dzambolat Tedeyev, the finished statue is set to take pride of place in Tedeyev’s home village in South Ossetia.

Speaking to the Moscow Times in his workshop, Khayev, a softly spoken man with an easy smile, expressed admiration for his subject’s war leadership and industrialization policies, while acknowledging the unsavory sides of his legacy.

“Of course there were repressions, but you have to remember that he did extraordinary things for the people,” said Khayev with a slight shrug.

“My grandfather fought in the war and he never said a word against Stalin,” he added.

“Essentially a religion”

For North Ossetia’s Stalin critics, their compatriots’ continuing devotion to a dictator who did not spare Ossetians from bloody repressions evokes a mixture of bemusement and dismay.

“Modern-day Stalinism is essentially a religion in Ossetia,” said Alik Pukhayev, a prominent Vladikavkaz blogger.

Pukhayev pointed out that Stalin’s ostensible Ossetian origins did not stop him from purging much of the local intelligentsia in the 1930s, or allocating South Ossetia to neighboring Georgia, a decision that has resulted in two wars and a mass exodus of Ossetian refugees from Georgia since the collapse of the U.S.S.R.

Further complicating Stalin’s local legacy is his brutal treatment of the Ossetians’ neighbors and rivals.

In 1944, Stalin ordered the deportation to Central Asia of a string of ethnic groups he falsely suspected of collaborating with German invaders. Among them were the Ingush, Muslim neighbours of the Ossetians.

The Ingush return from exile — during which as many as a quarter of them perished — touched off a series of disputes with the Ossetians, which eventually spiraled into violent conflict in the early 1990s, and deep mutual distrust to this day.

“It’s possible that what Stalin did to the Ingush plays a role in how positively Ossetians feel about him,” said blogger Pukhayev.

“But that’s ridiculous - after all, he purged Ossetians too!”

Instead, with pro-Stalin feeling having only deepened with time, Pukhayev and other local Stalin critics are left casting around for explanations for their homeland’s peculiar relationship with the dictator.

“Stalinism is our national Stockholm syndrome,” he said, referring to a psychological condition in which hostages develop an emotional bond with their captors.

“There’s no other way I can explain it.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.