Russian foreign policy is likely to continue to dominate global news headlines this year after a tense 2021.

Russia’s military build-up on the Ukrainian border has set the world on edge, raising fears of an invasion.

In neighboring Belarus, the Kremlin has moved closer to fully-fledged integration with the country, whose embattled strongman President Alexander Lukashenko looks increasingly isolated from the West.

Looking west, the jailing of Kremlin-critic Alexei Navalny further strained relations with Europe, while across the Atlantic, the election of Joe Biden fundamentally changed the course of American foreign policy toward Russia.

Russia also tried to extend its global footprint, by cooperating with post-coup Myanmar and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan.

And as the world continued to struggle with the coronavirus pandemic, Russia attempted to boost its global image through “vaccine diplomacy,” but inconsistent vaccine production and a murky middle-man selling vaccines in the developing world ultimately led to a string of scandals that did Russia’s reputation more harm than good.

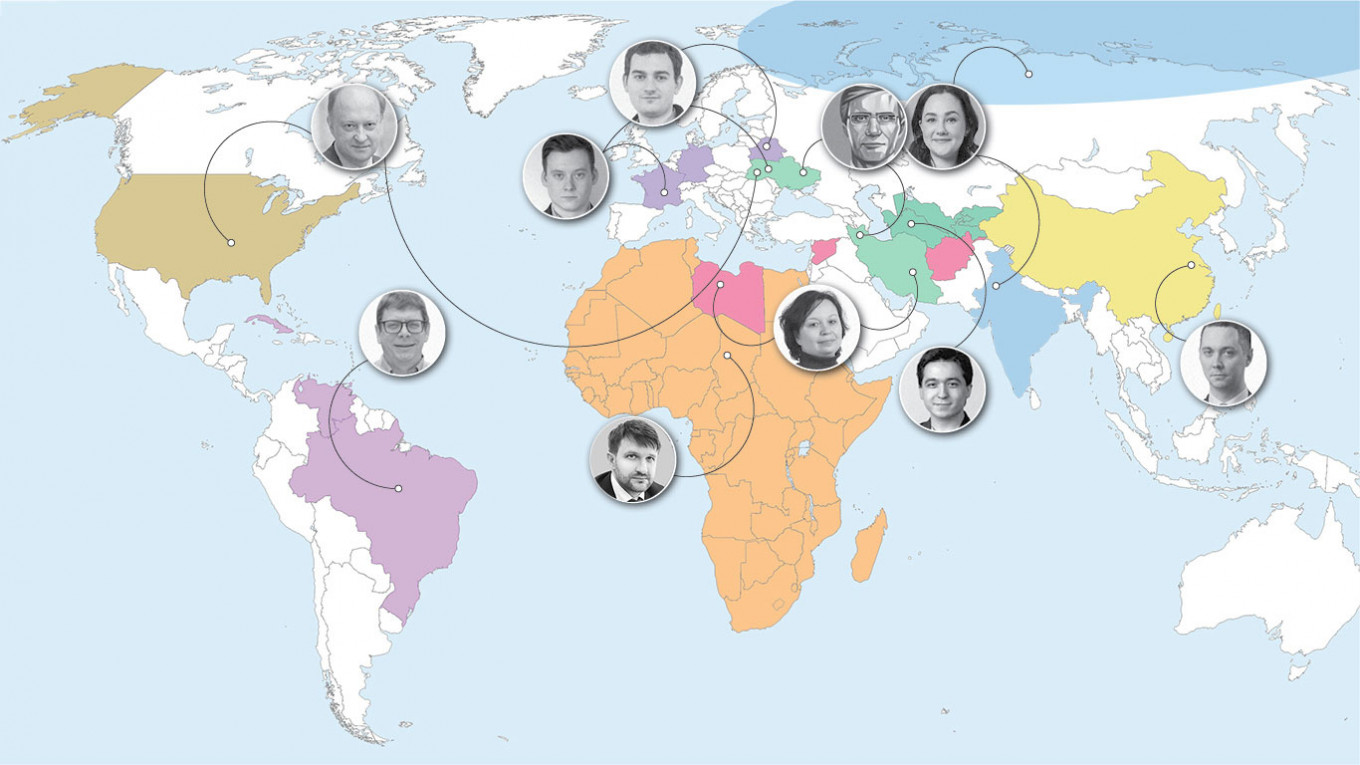

What does Russia hope to achieve in 2022? The Moscow Times asked 10 leading experts in Russian foreign policy to give their predictions for the coming year.

Russia-China relations will deepen in 2022

Alexander Gabuev, senior fellow and chair of the Russia in Asia-Pacific Program at the Carnegie Moscow Center

Two years of the pandemic have shown the resilience of Russia-China ties.

In 2021, trade volume grew to nearly $140 billion, setting another historic record.

This figure reflects not only high commodities prices this year, but also increased shipments of natural gas via the “Power of Siberia” pipeline and growth in volumes of Russian coal exports to China.

In 2022 this trend is likely to continue, although exact trade volumes will be subject to volatile global prices. As China shifts away from domestic coal to cleaner fuels like gas, and Russia seeks to monetize its natural resources, Moscow and Beijing might find more joint projects.

Some of them will be unveiled during Vladimir Putin’s trip to Beijing in February, with a new contract for the “Power of Siberia 2” gas pipeline as the crown jewel. The political environment is also benevolent to the further deepening of China-Russia ties. Moscow’s conflict with the West is not going away, as demonstrated by recent events in Ukraine, raising the prospect of more U.S. and EU sanctions against Russia.

Beijing’s confrontation with the U.S. is also here to stay, even if the White House gets distracted by events in Europe or elsewhere. Despite some predictions, China-Russia entente is far from its peak, and 2022 is likely to serve as another testament to this.

Keeping the Middle East “stable in its instability”

Mariana Belenskaya, Middle East correspondent for the Russian daily Kommersant

It seems that Russian foreign policy is no longer focused on the Middle East, as it was for several years after the start of the military campaign in Syria. Russia is now moving along a familiar path — the situation is “stable in its instability” but Moscow has restored its authority in the region, established ties and assigned roles. The general task for next year is to increase trade with the countries of the region — including by expanding the grain market — and maintaining interest in Russian weapons.

Syria, which will remain Russia’s zone of responsibility for many years to come, is still a separate set of issues. It is important that the pacified territories do not once again turn into hotbeds of confrontation and that no global powers initiate new operations in the country. In addition, Russia hopes that Syria will gradually emerge from its international isolation. For its part, Moscow will continue trying to rebuild Syria’s infrastructure, at least to the extent that it can do so alone.

Russia might need to pay close attention to Libya, where it remains unclear how events will develop. Moscow maintains close contact with all the parties in the Libyan conflict but does not seek a central role in resolving the problems there — at least for as long as the situation does not become critical.

Two regional problems will require particular attention next year — the “Iranian nuclear dossier” and Afghanistan. The latter has become more strongly linked to the Middle East now that Turkey and Qatar have taken an interest in it.

As for Iran, Moscow will do everything in its power to bring all parties back to the Iran nuclear deal — the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action — as it existed prior to Washington’s withdrawal from it in 2018. Indeed, the answer to the question of whether a Nuclear Deal 2.0 will appear and how it will look largely depends on how events will transpire in the Middle East and what role each party in the region will play.

Peace in Ukraine is a victory in itself

Andrei Kortunov, director-general of the Russian International Affairs Council

It is hard to envisage a breakthrough or even significant progress in relations between Russia and Ukraine in 2022. The definition of success would be the ability of the sides to avoid direct military confrontation in Donbass, in the Azov Sea or along the Russian-Ukrainian border. The current political dynamic between Kiev and in Moscow is not conducive to the flexibility needed to move ahead with the implementation of the Minsk Agreements. At the same time, the change of government in Germany and the forthcoming presidential election in France make it very hard for the European members of the Normandy process to exercise the leadership needed to overcome the current stalemate.

One could expect the Biden administration to become a more active player in the situation around Ukraine in 2022, but the odds are that White House attention will be focused on ongoing U.S.-China rivalry and the Ukrainian crisis will remain a relatively low priority for Washington. Still, de-escalation is possible, as well as a new Russian-Ukrainian agreement for gas transit. If these modest goals are achieved in 2022, we might see less hostile and belligerent rhetoric coming out of Moscow and Kiev.

Further uneasy integration with Lukashenko in Belarus

Artyom Shraibman, Belarussian journalist and political commentator for the Carnegie Moscow Center

Russia's strategic goals in Belarus have remained unchanged for many years. Moscow, at minimum, wants to prevent the rapprochement of Minsk with the West, and at maximum, to strengthen its own influence in Belarus, which could outlive Alexander Lukashenko.

Further institutionalization of such dependence will be the plan for 2022. This includes promoting bilateral integration within the Union State, increasing Russian military presence in Belarus, and “helping” Minsk to reorient its trade flows toward Russia in response to Western sanctions. Not all of those ambitions will necessarily materialize, as Lukashenko retains some bargaining power.

For several years now, Moscow has been approaching financial support for Lukashenka conservatively. The volume of indirect subsidies, discounts on gas and oil and loans are either decreasing or not growing. The Kremlin gives Lukashenko as much as is necessary to keep his regime afloat, but the idea of more generous investment in Belarus has long been unpopular in Moscow.

At the same time, one should not expect Putin to exert tough pressure on Lukashenko in order to speed up the transfer of power in Belarus. At best, the Kremlin might be ready to push the friendly regime toward controlled transformation, but Russians will not actively undermine Lukashenko’s rule.

Moscow's long-standing problem with Belarus is the lack of reliable alternatives to Lukashenko.

Despite Biden-Putin respect, Ukraine means a bumpy ride in relations with America

Vladimir Frolov, political columnist and former Russian diplomat

In 2022, the U.S. and Russia will test the resilience of the respectful adversarial relationship they have transitioned to after the Geneva summit last June.

“The spirit of Geneva” has helped keep confrontation at an acceptable level through dialogue on strategic stability and cyber threats and with regular interaction between national security advisors.

The presidential talks have demonstrated grudging respect and an ability to communicate grievances and threats clearly, but calmly, while opening new avenues for dialogue.

Washington dangles inconclusive talks to curb Russian unpredictability, while Moscow views engaging with Biden as the best way to address Russia’s long-ignored concerns without changing course.

There is even a rare U.S.-Russia mind-meld over the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) Iran nuclear deal negotiations, with Iran’s intransigence providing the incentives.

Disagreements, however, will remain. The stand-off over bilateral diplomatic presence has degenerated into the grotesque, with spy agencies unable to agree on rules for acceptable espionage activity. Resolving the impasse will require Moscow to remove its designation of the U.S. as a “hostile power.”

Ukraine, NATO enlargement and Russia’s rightful place in the European security order will remain the key battlegrounds in 2022.

Moscow harbors great expectations after Biden’s promise to discuss Russia’s concerns over NATO enlargement “among the five major NATO allies” signaling acceptance of Moscow’s preferred format on European security.

In Ukraine, Russia’s demands have moved beyond the implementation of the Minsk agreements and are now in “Finlandization territory.” Moscow’s insistence on legally binding guarantees of the definitive end to NATO enlargement in the former Soviet Union has narrowed the scope for face-saving diplomacy.

Biden will have a short time frame in 2022 to negotiate an acceptable accommodation with Putin on Ukraine and European security. Russia’s posture is unlikely to change before significant diplomatic progress towards meeting Moscow’s objectives. It will be a rough ride.

Crucial elections in Latin America could tilt the balance of power in Russia’s favor

Vladimir Rouvinski, professor at Icesi University in Colombia

In 2021, Russia managed to position itself as one of the major suppliers of the Covid-19 vaccine to the region, although mainly supporting countries with friendly relations to Moscow

Meanwhile, key Russia ally President Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela, not only survived 2021 but also started strengthening his position in the region thanks to a new left-wing wave on the continent.

In the coming year, Russia will be closely watching several important presidential elections, including Colombia, where a left-wing candidate is projected to be the likely winner. In Brazil, the very popular left-wing former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is expected to announce his bid for the presidency in early 2022. Wins for both left-wing candidates will dramatically change the Latin American political map and open new opportunities for Moscow to strengthen its ties in the Western Hemisphere.

However, Russia also faces challenges. One of them is the shortage of tangible resources to support its allies in this part of the world. This is most evident in Cuba, where the situation is deteriorating rapidly and Moscow has so far provided minimal aid. The continuous tensions with Washington over Ukraine may incentivize reciprocity-driven Russia to pay more attention to Cuba, located just 129 kilometers (80 miles) from the U.S border.

No easy answers in Europe

Anton Barbashin, editorial director of Riddle Russia

It is almost impossible, looking at the end of 2021, to see a bright future for EU-Russia relations in 2022. The best case scenario is that they won’t get much worse.

We can point to three major themes that will define this relationship next year — Ukraine, Belarus and the future of gas. In each of these cases the EU’s goal is to minimize damage, while Russia will undoubtedly be ready to up the risk-taking, assuming the EU will be the first to blink.

The most heated and potentially most devastating is the tension over Ukraine and the role of NATO in European security. While Moscow certainly blames Paris and Berlin for failing to press Minsk II and is now betting on Washington, it will be the EU that will have to pick up what’s left after the likely fallout.

The blow might be softened by prompt Nord Stream 2 certification, but as of now it looks like stable gas prices are not in the basic scenario for 2022.

Peaceful or not, 2022 will not be relaxing.

Will the Arctic remain the sole region of cooperation in 2022?

Elizabeth Buchanan, lecturer in strategic studies with Deakin University at the Australian War College

Will 2022 mark the end of the Arctic’s “low tension” post-Cold War run or will the Arctic remain “isolated” from Russian-Western strategic tensions elsewhere? Pundits worldwide will no doubt keep a watchful eye on any potential spillover from Russia’s current Ukraine trajectory into the Arctic.

Since 2014, Russian-Western ties in the Arctic have remained largely cooperative, indeed even collaborative via multilateral vehicles like the Arctic Council.

Russia knows that the future economic resource base of the country does not rest on its Eastern European doorstep, but on its Arctic frontier. Plunging the Russian Arctic Zone into conflict is therefore not part of Russia’s strategic playbook. Working to silo the Arctic from tensions far beyond the region will remain a lynchpin of Kremlin security planning and outlook.

The real geopolitical and strategic gains and achievements for Moscow in the Arctic will remain nested in Russia’s bilateral energy engagements. In 2022, I expect an enhanced diversification strategy with regard to Russia’s economic partners and stakeholders in its various Arctic energy ventures. Bilateral Arctic ties with India will be central to offsetting any Russian overreliance on Chinese capital.

Russia will try to gain from the Taliban’s threat in Central Asia

Temur Umarov, research consultant at Carnegie Moscow Center focusing on Central Asia

In 2022, security concerns in Afghanistan will continue to be the priority for Moscow in Central Asia. Russia will see a window of opportunity to regain its reputation — which is being challenged by China — as the only reliable security guarantor in Central Asia against the uncertainties that the Taliban regime brings.

This means that in the upcoming year Russia will intensify its cooperation with the security agencies in Central Asian nations. Russia will also be hoping to push through its integration projects with countries previously skeptical of joining. Uzbekistan, for instance, is now seriously considering joining the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union.

Overall, Russia’s leadership will want to see a stable and safe Central Asia in the next several years. The closer we move toward 2024 presidential elections, the less energy the Kremlin will have for anything other than its domestic issues.

Moscow will therefore try its best to help the political leaders in Central Asia to become stronger and more stable. However, this is not going to be an easy task, especially in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan.

More than symbolism at the 2022 Russia-Africa Summit

Andrey Maslov, head of the Center for African Studies at Moscow's Higher School of Economics, with researcher for Intexpertise LLC Sviridov Vsevolod

The volume of Russian-African trade increased this year for the first time since 2018, diversifying both geographically and in the range of goods traded. Shipments of railway equipment, fertilizers, pipes, high-tech equipment and aluminum are growing and work continues on institutionalizing the interaction between Russia and the African Union.

The second Russia-Africa Summit is planned for 2022. In February it will be announced where and when it will be held — most likely in Russia in November — and in which format. Preparations for the second summit will shape the Russian-African agenda, visits will become more frequent and Africa will receive greater coverage in Russian media.

Instead of measuring the success of the summit by how many African leaders attended, as happened in 2019, the parties will finally give greater attention to the substance of the agenda, which is already under development.

Russia will try to increase its presence in Africa while avoiding direct confrontation with other non-regional players.

A number of conflicts are also causing alarm, primarily those in Ethiopia and in Mali, from which France and the EU are withdrawing their troops. In 2022, Russia will try in various ways to play a stabilizing role for Africa and assist in confronting the main challenges it faces — epidemics, the spread of extremism and conflicts, and hunger.

A dialogue will also begin on Africa formulating its own climate agenda. Africa is beginning to understand that it does not need a European-style green agenda and will demand compensation from the main polluting countries for the damage the climatic changes have caused to the ecosystems of African countries. Russia is likely to support these demands.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.