When Alexei Navalny returned to Russia at the start of 2021, the country’s leading opposition figure and his army of followers sensed their moment.

“We need to fight,” Navalny told a crowd of reporters on Jan. 17, just before passport control at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, where he had landed on a flight from Germany after four months of medical treatment for poisoning by a nerve agent.

“I’m not afraid of anything — and you shouldn’t be either,” Navalny said. Moments later he was arrested and taken away for interrogation.

His return, arrest and subsequent imprisonment triggered a wave of protests, an aggressive crackdown and a new era of repression and restrictions against Navalny’s allies and a host of other independent voices.

Dozens of critics of the regime fled abroad, fearing lengthy prison sentences if they stayed in Russia, and the country’s opposition was all but neutralized by the end of the year.

The lack of protests following parliamentary elections in 2021 compared starkly with the wave of street rallies that had electrified the opposition in January and February — showing how effective the Kremlin’s crackdown has been in overcoming the immediate threat posed by Navalny’s return earlier in the year.

Here’s a recap of how a very bad 2021 unfolded for Russia’s opposition movement:

January

- Alexei Navalny returns to Russia after four months in Germany recovering from a poisoning by the nerve agent Novichok. While he was away, the Bellingcat investigative outlet published a story naming the security services operatives who were allegedly behind the attack in Tomsk in August 2020.

- Navalny is arrested upon arrival for violating the terms of his parole while in a medically induced coma in Berlin.

- A day later, Navalny’s team publish an investigation into “Putin’s Palace” — a multi-million dollar mansion on the Black Sea which they say is financed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s allies on his behalf. The investigation goes on to become the most-watched video of the year on Russian YouTube.

- Tens of thousands take to the streets in a series of rallies in more than 100 cities across the country against Navalny’s imprisonment. They are the largest unsanctioned protests for a decade and are met with the most forcible reaction from the authorities ever recorded, with almost 10,000 protestors detained across two weekends.

February

- Navalny is found guilty of violating his parole and sentenced to 2.5 years in prison. He tells his followers not to lose hope in a statement in court: “What matters most is why this is happening. This is happening to intimidate large numbers of people. They’re imprisoning one person to frighten millions. We’ve got 20 million people living below the poverty line. We have tens of millions of people living without the slightest prospects for the future. Our whole country is living in this mess, without the faintest of prospects.”

- Key Navalny aides are placed under house arrest for their role in organizing mass street protests. They include press secretary Kira Yarmysh and Lyubov Sobol, a lawyer at Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation

April

- Navalny dissolves his nationwide campaign headquarters as a Russian court names the organization “extremist,” leaving employees and volunteers open to criminal prosecution.

- Authorities detain Ivan Pavlov, founder of the Team 29 legal organization, Navalny’s lawyer and one of Russia’s top defense lawyers for cases involving journalists and civil society groups. He later flees Russia, telling The Moscow Times police searched his apartment and took a number of documents, but left his travel passport — a common tactic used by authorities to encourage people to leave the country.

- A number of independent media outlets, including Meduza, are named foreign agents and the Kremlin’s campaign against independent journalists, including the editor of the investigative iStories outlet, continues.

May

- A protester who was detained at the pro-Navalny rallies in January is handed a 4.5 year jail sentence — the most severe punishment among dozens of cases opened.

June

- A Russian court declares Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation and other political bodies linked to the Kremlin critic “extremist” organizations, outlawing their activity in Russia.

- Russia amends its law on “undesirable organizations” to make it much easier to launch criminal proceedings against people involved with organizations labelled “undesirable,” including those who cooperated with the organization before it was named “undesirable.”

- Prominent Kremlin critic and former opposition lawmaker Dmitry Gudkov flees Russia following raids on his and his family's properties. He had been planning to stand for election in September’s parliamentary elections. His arrest marks the start of a widespread pre-election crackdown against candidates who were planning to stand for election.

July

- Russia blocks access to almost 50 Navalny-linked websites.

August

- Lyubov Sobol, a key Navalny ally, and his spokeswoman Kira Yarmysh leave Russia — the most high profile departures of Navalny aides since his imprisonment. They join a growing list of political emigres leaving under threat of arrest ahead of parliamentary elections in September.

September

- Navalny’s team unveils its “Smart Voting” strategy — a tactical voting system designed to oust United Russia candidates in the upcoming parliamentary elections. The Kremlin instantly reacts, blocking Navalny’s websites and mobile applications, and asking Apple and Google to delete Navalny material, including public Google Docs, from their servers.

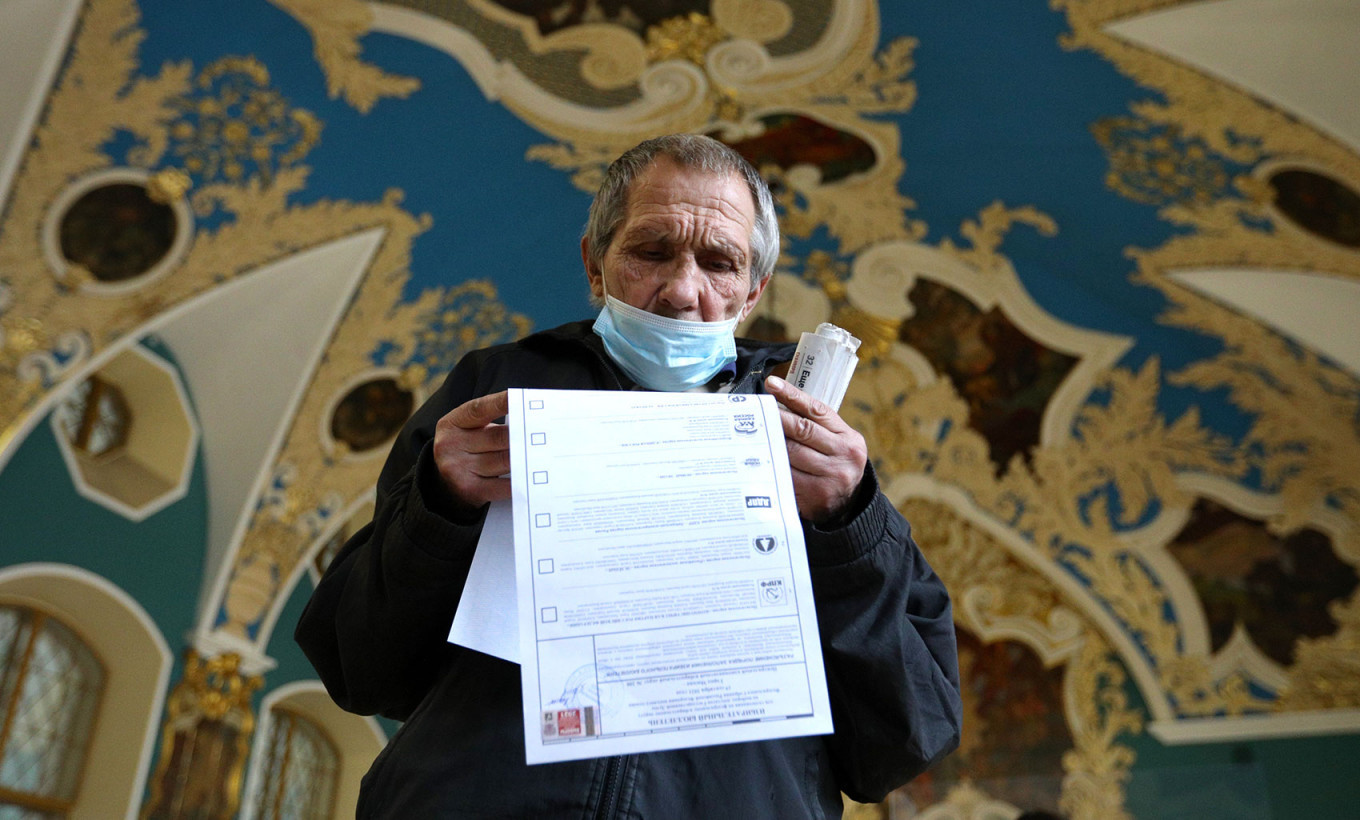

- The ruling United Russia wins a large majority in elections to Russia’s lower house of parliament, the State Duma. The vote is marred by allegations of fraud. No Navalny-linked figures were allowed to stand and almost all independent opposition candidates were barred from running.

- An ongoing crackdown against independent media outlets intensifies within days of the vote, with Mediazona becoming the latest outlet named a “foreign agent.”

October

- Following a spate of arrests and detentions of political activists in Russia, the Memorial human rights group estimates there are as many political prisoners in Russia as during the late Soviet era.

- The head of the Communist Party in Moscow is detained on suspicion of illegal hunting after he was found with a dead elk in his vehicle. He is later stripped of his parliamentary immunity in a move commentators said is part of a wider crackdown against the party — part of the so-called “systemic opposition” — by the Kremlin.

November

- A Russian court launches the first retrospective legal case against a member of Navalny’s team for involvement with the organization. The action is widely criticized by lawyers and human rights defenders.

- More former managers of Navalny’s regional headquarters move abroad. The Kommersant news site estimates that at least 14 of the 38 regional heads left Russia in 2021, with many moving to Georgia or the Baltic states.

December

- Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, one of the few remaining independent media outlets in Russia that has not been labeled a “foreign agent,” is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his decades-long campaign for freedom of speech. He dedicates his award to his slain colleagues and decries growing threats to freedom and human rights in Russia and its neighboring countries.

- At least five former regional coordinators of jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny’s network were detained nationwide on charges of organizing an extremist group — the latest use of controversial laws designed to target Navalny’s former associates, despite the group having disbanded earlier in the year.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.