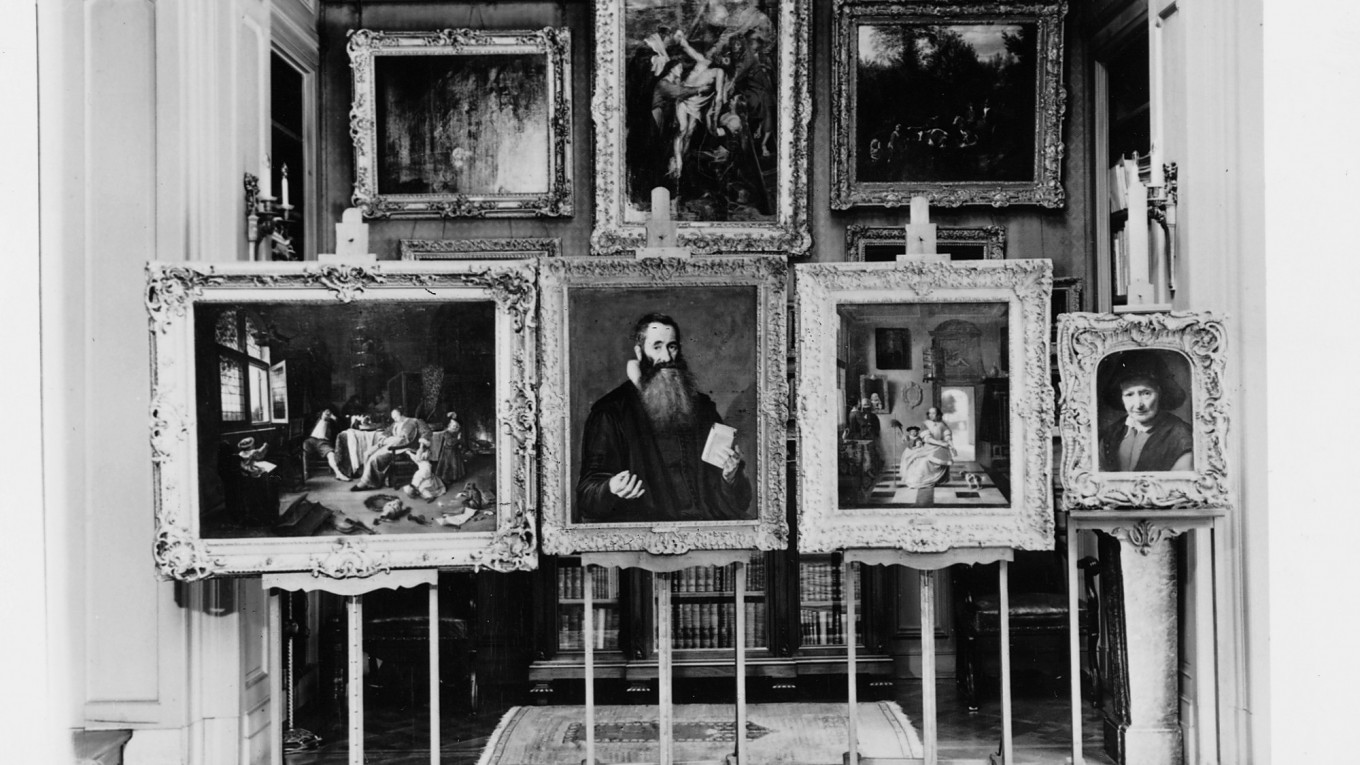

1,148,908. This is the number of Russian works of art that the Russian State Commission for the Restitution of Cultural Treasures has estimated were lost when the Nazi army attacked the Soviet Union.

During the Second World War, German soldiers destroyed or looted Russian museums and palaces — as detailed in much research. Most of the works were never returned to the Soviet Union or Russia, which has complicated relations between Russia and Germany as well as between Russia and the rest of the European Union.

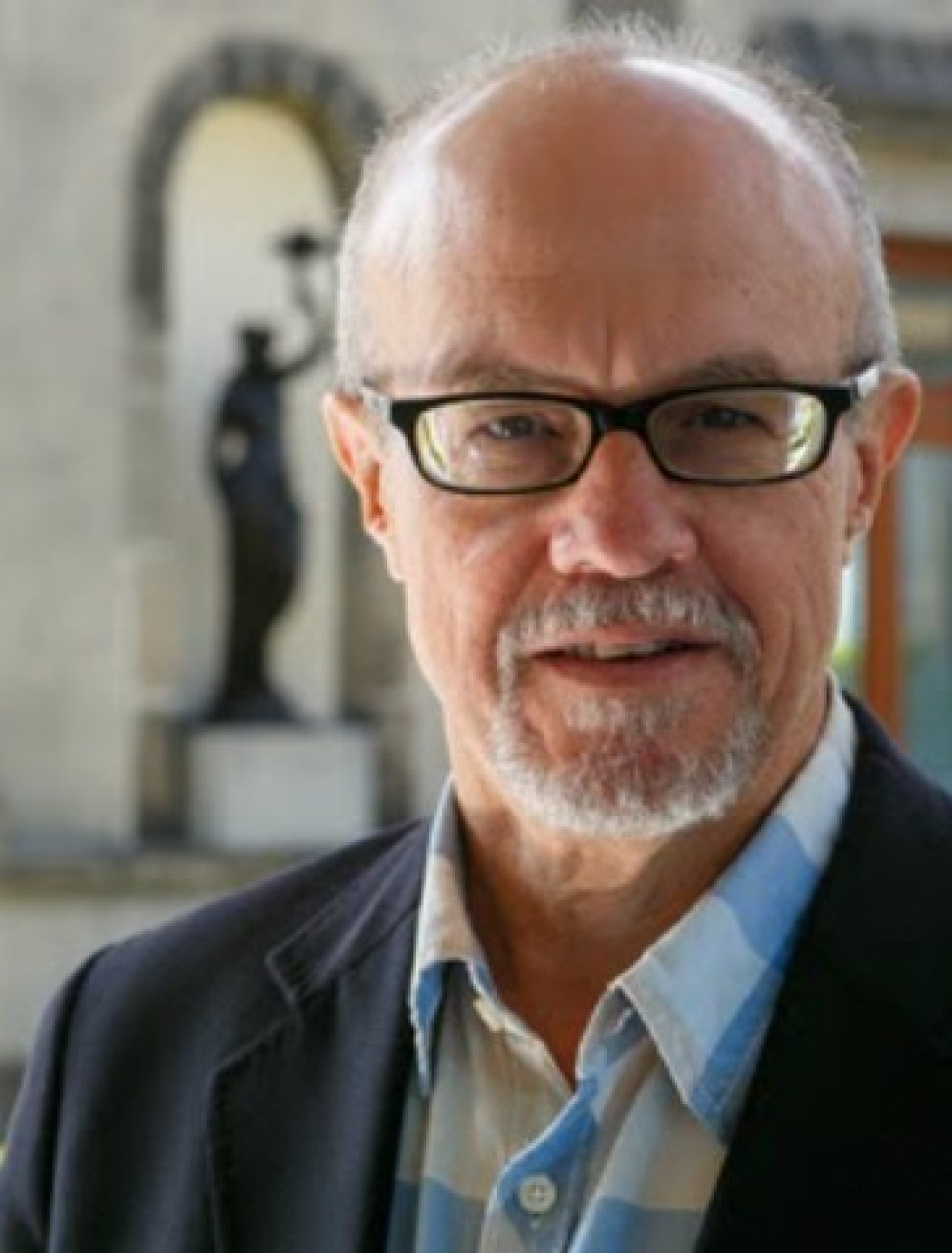

Nothing would have been known about this if it had not been for a Puerto Rican journalist who has been on the trail of works stolen by the Nazis since the 1980s. Thirty years later, his epic work has been translated into Russian. To celebrate this launch, the author gave a lecture at the Cervantes Institute in Moscow.

"The Lost Museum: The Nazi Conspiracy to Steal the World's Greatest Works of Art" by Hector Feliciano has just been published by Slovo Books. The investigation, which has taken this journalist almost his entire life, sheds light on an estimated 20,000 works of art plundered by the Nazis that in many cases went to museum collections in Europe and the United States.

We asked Feliciano about the Russian works of art taken out of the country and the complex and often horrifying history of wartime looting.

When you were working as a Paris correspondent for The Washington Post, you learned about artworks looted by the Nazis. If you hadn’t written about it, would it have become well known?

That’s hard to say. At the time there were no serious books on the subject. When I started looking in the archives, the only things I found on the subject were some New Yorker articles from 1945-46… I have an investigative tendency — it’s my weakness. I didn’t want to just write an article about it, I wanted to find the works. It’s a fascinating subject.

What spurred you on?

In the French National Archives I saw many sensitive documents…When I showed the archivist the list of what I wanted to consult, she looked at me strangely and then asked me what my job was. I said I was a journalist. Her response was: “Sir, you will never have access to these documents.” No one should ever say that to a journalist! I managed to convince each family to request the documents themselves, since they had the right to request their family file. They then passed them on to me. When I had several files, I began to see how the looting happened.

You were helped by German diligence in their inventories, weren’t you?

They made three inventories for each collection they stole. Each inventory had a code for each family and a number for each object. For example, for the Rothschild family, the code was R, and the numbering ranged from R1 to R5002 or R5003. They did it because, first of all, they never thought they were stealing, and secondly, they never thought that they’d lose the war. That’s why they never destroyed these documents. They were my accomplices without knowing it. With inventories it was much easier to locate each work.

Did the museums that had art stolen by the Nazis collaborate with them?

Some yes, others no. Some were accomplices without knowing it, but and others took looted works knowingly. For example, in the case of Austria, there were many curators who looted works during the war that they knew from private collections.

Did you receive threats before, during or after you wrote the book?

Yes, there were calls home and people who told me to stop my work. A large art house took me to court for defamation since I found documents implicating them in collaboration with the Nazis from the moment Hitler came to power. They took me to trial and spent five years litigating. I won all the cases, but it cost me a lot of time and money. But as a journalist I grew up with the idea that the written word had consequences, so seeing my book create these was one of my greatest professional and personal satisfactions.

The book is now translated into Russian, and many of us want to know what happened to the theft of works of art during World War II in the country. More than 150 museums are said to have been looted by the Germans.

Note that there was one Nazi policy about culture and the arts towards Western Europe and another towards Eastern Europe and Russia. The Nazis were viscerally anti-communist, and the Nazi regime was also racist. They felt superior to the Slavic world and its culture. Hitler didn’t want to create satellite-states in the East, but to integrate them into the Reich, as they did with Poland.

Their policy toward works of art and cultural monuments was not to loot but to destroy and leave nothing behind. They had a lot of hatred. The Slavs were, for them, usurpers of a Western culture that did not belong to them.

Knowing that changes your perspective. When I started working on this topic, I didn't know what I know today. Little by little, I began to understand — not justify — why the Duma declared the works looted by the Red Army from Germany as part of the Russian national heritage. Ideally, those works should have been restored.

Perhaps the most spectacular case is that of the Amber Chamber.

I spoke with some people who worked on the subject, and they thought that the rooms had been in trains that were bombed. But even if something survived the bombing, amber doesn’t keep well outdoors, so there is probably nothing left.

What was the biggest disappointment of your work?

I have always said that this research made me a sadder person, but wiser. Indeed, I met many wonderful people, but also some very perfidious people.

The big question: How much art looted by the Nazis remains unaccounted for?

In just France, the Nazis methodically stole about 100,000 works of art. To get an idea of this figure, keep in mind that the MoMA collection has 2,500 pieces in total. Of these 100,000 works of art, about half have not been found, or rather have not been returned to their owners. In Eastern Europe, including Russia, at least 300,000 works have not been found. Of course, there was theft of not only works of art but also of a million manuscripts and books, which are very difficult to recover. And half a million pieces of furniture, which were also very difficult to trace. These are like open wounds.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.