A hand-written open letter has been doing the rounds on social media and then the press, reopening the painful issue of official torture and underworld abuse within the Russian prison system.

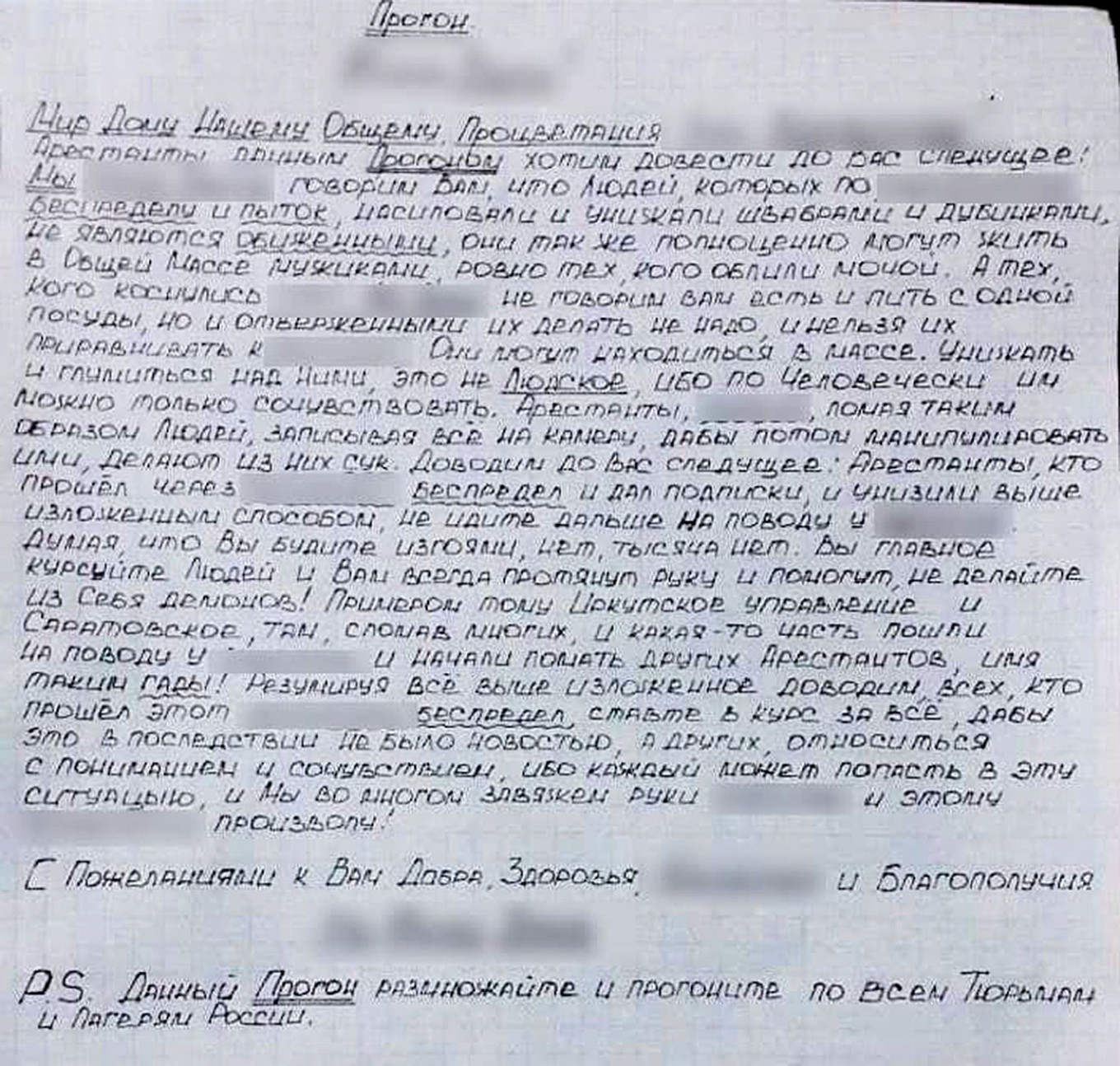

This purports to be a progon (“run” or “alleyway”), a statement from a collection of senior figures within Russia’s underworld. These are typically used to address key issues of the moment, from the correct conduct of vory — “thieves,” the term for the members of the criminal subculture — to whether or not one or other of the authority figures known as vory v zakone (literally, “thieves in law,” but better translated as ‘thieves within the code) were legitimately ‘crowned’ in their new status.

Brutality as tactic

The topic of this open letter, though, is a practice revealed in caches of disturbing videos from prisons across Russia that were recently leaked, showing inmates being urinated on, beaten, and raped with implements from truncheons to mop handles.

These leaks caused an understandable furore, a series of criminal cases, and the “retirement” of the head of FSIN, the Federal Corrections Service (he was replaced by an outsider, a police officer).

What made the brutal and horrific all the more awful was the way that, in the traditional code of the vory, anyone who allows themselves to be treated this way becomes an outcast, known by a variety of names such as a “rooster,” ostracised, even barred from eating with fellow prisoners, and often facing violence and intimidation from their peers.

This actually is part of the reason for the practice, and likely for the video recording of what is, after all, a criminal act.

Those who experience it become vulnerable to blackmail, because of the consequences of being outed as having been “lowered.” In some cases, this is done to extort money, sometimes sheer sadism, but often it is also as a brutal instrument of control, forcing prisoners to inform or even actively support the prison camp authorities.

Humanitarian pragmatism?

The open letter calls for a relaxation of the former tough line against these “lowered” prisoners.

While to some this demonstrates a degree of compassion, it continues to consider them unclean.

Although one “can only sympathize with them,” there is no envisaged relaxation of the structures against eating with them for example. It is hard to see this as a genuine break with the violent, exploitative and homophobic traditions of the criminal code, though, it is likely motivated more by pragmatism. By stopping the full exclusion of such victims of abuse, it is meant to reduce the leverage the threat of rape gives the prison authorities.

There is still debate about whether the letter is genuine. It certainly conforms to the style, language and forms of the typical progon, but is unusual in that it is simply signed “a mass of thieves” whereas usually, it is crucial that the individual vory v zakone endorsing it are identified, precisely to give it authority.

For some, the absence of such signatories reflects the impact of Article 210.1 of the Criminal Code, introduced in 2019. This allows for prosecution not on the basis of a specific crime, but simply for being a senior figure within an organized crime group.

The consensus, though, seems to be that it is genuine, not least because other, similar documents have been doing the rounds within the prison system.

Code in motion

What does this actually mean, though? The traditional code of the vorovskoi mir, the “thieves’ world”, is very much in decline.

Whereas once vory v zakone were pretty much universally respected within the underworld, increasingly the title is bought or conferred by one senior gangster on his allies and cronies, without looking for a wider consensus as to whether they were worthy.

The old code is especially less powerful with ethnic Russian gangsters, as their counterparts from the Caucasus cling most strongly to its honorifics and mythology. It is also more evident within the prison system than without it.

Nonetheless, the code is a living one, and can and does change from time to time, to reflect the challenges and opportunities of the time. It was essentially rewritten by the victory of the so-called “bitches”, suki, pragmatic collaborationists who won an intra-Gulag war in the 1940s and 1950s.

It was later amended to allow dealing in drugs and then again to reflect the fragmentation of the Soviet Union. To a degree, it is being rewritten now not through conclaves of vory v zakone, but by the practice on the ground and in the prisons.

This is therefore a new piece of pragmatism, to try and reduce the power of equally ruthless prison authorities over them (and it is worth re-stating that such brutal practices are neither legal nor universally applied).

Power grab?

It may also be a piece of underworld politics.

According to some reports, amongst the kingpins behind the letter was Zakhary Kalashov, known as Shakro Molodoi, ‘Shakro the Younger.’ Although currently serving a ten-year prison term on extortion charges, he is one of the biggest beasts in the Russian underworld, and a perennial contender for the informal status of the boss of bosses.

Russia’s organized crime scene is too big, too fragmented, and, increasingly, too internationalized for there to be any one dominant figure, structure or even subculture.

Nonetheless, struggles for supremacy over regions, markets or particular elements of the vorovskoi mir are common, driven by ego and self-interest. That Shakro the Younger may also be throwing his weight behind a further revision of the code, one that saves many convicts from abuse and denies the authorities another lever, may also thus be part of a power grab, an attempt to elevate himself as a representative of the traditionalist criminals specifically within the prison system.

In this way, a one-page letter may well be illustrating not simply the continued use of brutal and illegal tactics by FSIN authorities, but the continued flexibility of the criminal code — and the different ways in which vory v zakone prosecute their own struggles for power and legitimacy.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.