“Fat Lyuba” is a humiliating nickname, especially for a boy. But that’s what bullies called Oleg Lipovetsky throughout his high school years.

Decades later, the teenager who once dreaded going back to school, has become a handsome and popular actor. Yet those memories are as vivid as ever, and bullying in Russia seems only to be growing: According to a recent sociological research conducted by the Mikhailov & Partners agency, more than half of Russia’s teenagers — 52% — say they are bullied.

In the play “Fat Lyuba,” which is loosely based on Lipovetsky’s autobiographical story called “Life Number One," the main character goes through all nine circles of bullying hell, from verbal to physical abuse. It ends horrendously. Schoolboy Oleg is trying to do pull ups when one of his classmates pulls down his pants. Oleg falls to the ground as the kids jeer.

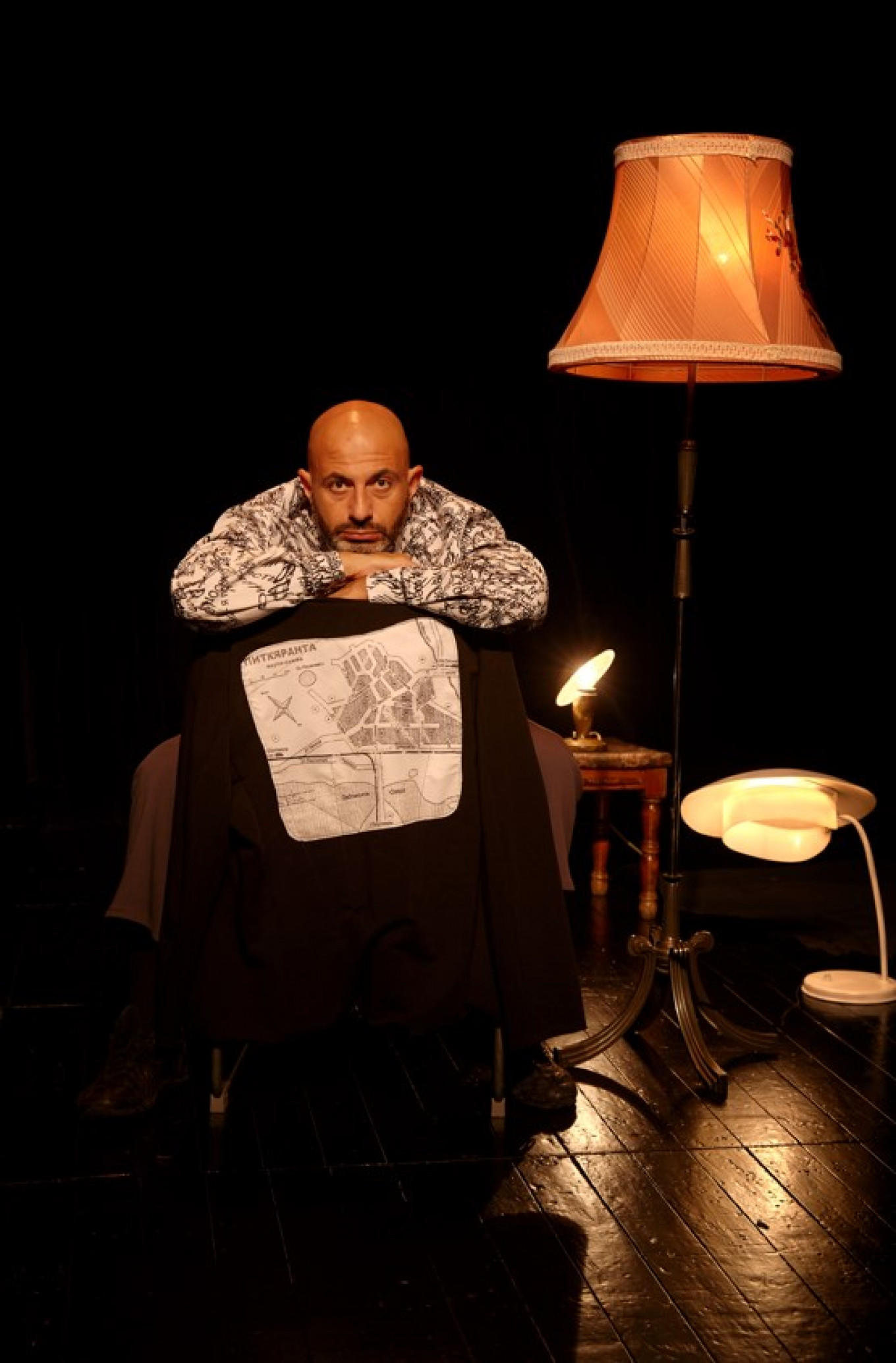

It is hard enough to entrust such painful memories to paper, but showing them on stage to the public takes courage. Yet this fall Lipovetsky has turned his challenging childhood experience into a theater production, directed by Yulia Kalandarishvili and supported by the privately funded Theater Project 27. What’s more, it is a one-man-show:Lipovetsky confronts his painful memories alone in front of the audience.

“‘Life Number One’ is a very personal piece of prose," Lipovetsky told The Moscow Times. “It’s one thing to write it and quite another to say it out loud from a stage. I didn’t think it would be so difficult. Usually, an actor makes an effort to get close to a character, but for me, on the contrary, I needed the strength to look at the character from the outside. After all, he lives inside me.”

The show’s program shows Oleg as a teenager when he was most bullied.

On stage Lipovetsky becomes a living firework of emotions as he relives almost a decade of his life in this 90-minute one-man show. “Fat Lyuba” is not a lament or a sentimental journey. Lipovetsky makes the months spent on a diet at a clinic sound like a thrilling adventure, complete with starting a band and falling in love for the first time. The audience members almost hold their breath as they follow the story of how he conquered his fears, and then cheer at how creative, optimistic and adrenaline-driven this process can become.

For Lipovetsky the production has become a kind of declaration of love to his family. He stressed the show is meant not only for the teenagers but for their parents, too. He said his own mother was overwhelmed by the performance and confessed she had no idea how hard things had been for her son. “She told me she was sorry that they didn’t find out about my problems at the time,” Lipovetsky said. “It was really hard for my mother to watch the show. I hope that families who see the show will use the opportunity to step in before things get out of control in their children’s lives.”

Not alone

“Fat Lyuba” has a therapeutic component. Audiences are invited to share their own memories on the show’s website. Some of the stories are then printed on the programs of the show, which is being performed across Russia, from St. Petersburg to Kaliningrad to Petrozavodsk.

Irina Gaidova, now aged 37, was one of the viewers who chose to tell her own story. She remembered being a tall, skinny 10-year-old who wore glasses and had thin hair. She was made fun off and called “blind.” “On top of my looks, I was extremely shy and had a horrible time fighting back against the bullies,” Gaidova told The Moscow Times. “They would grab my stuff and start throwing it around […] when I was in 1st grade, I once wet myself at school. I was teased about it until I was in the 9th grade. I only got friends when I was in the 10th grade in a vocational school.”

Oleg Lipovetsky and the show’s director Yulia Kalandarishvili are convinced such productions, along with the discussions that they raise can help create a collective immunity to bullying.

“No less than six members of our production team prove that problems with appearance in teen years vanish by adulthood,” the team writes on the project’s website. “It’s very important for us to tell teenagers that these issues are not the end of the world. They are just temporary.”

For more information about the play and where it will be shown, see the site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.