Although few Russians know that it was former U.S. President John F. Kennedy who first popularized the saying, “Victory has 100 fathers, but defeat is an orphan”, they like repeating it so much that one might say it has now become part of the Russian culture.

However, this adage doesn’t seem to apply to the mass protests for fair elections in 2011-2012 because, although everyone admits that those demonstrations ended in defeat, many people are still vying to be considered the father of that defeat.

For the first time in modern Russian history, tens of thousands of indignant citizens took to the streets of Moscow and other large Russian cities and, over many months, peacefully but persistently demanded respect for their rights.

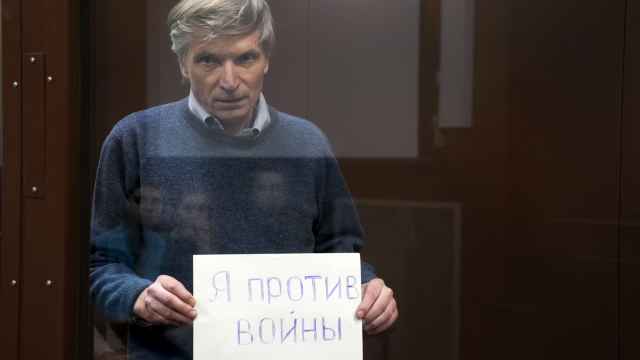

One year later, that wave of civic enthusiasm gave way to despondency as the authorities responded with criminal cases and police violence, a crackdown on freedoms, media owners who had indirectly supported the protests replaced with Kremlin loyalists, and public figures who had delivered speeches at the rallies subjected to coordinated harassment. Several non-conformist deputies of the State Duma — the same Duma that had been elected with the help of falsified results — were even forced to leave the country.

For all of the next 10 years, we have witnessed the Kremlin’s reaction to the sudden humiliation it suffered back then. The increasingly repressive measures, the spate of criminal cases, the new laws against “foreign agents”, proxy wars and state television’s ever more toxic propaganda — all this is a consequence of those peaceful rallies.

And if Russian leaders consider the rally on Bolotnaya Square on Dec. 10, 2011 as “ground zero” in this battle, then they see the country’s intelligentsia as the masterminds behind the attack on their authority and have pushed to alienate it from the state ever since.

The Kremlin propaganda machine has waged a war against the intelligentsia, portraying it as the driving force behind the protests, as funded by the West, as pro-gay and pro-Ukraine — in short, as pro-everything that ordinary working Russians oppose.

That is why, when the anniversary of those events rolls around every December, all the numerous “fathers” of that defeat among the Russian intelligentsia (yours truly included) engage in painful reflection on the question of what we did wrong.

Setting aside the somewhat hackneyed remark that painful reflection has been a hereditary trait of the Russian intelligentsia since the time of Chekhov’s plays, let us ask a better question instead: Is there an error in this logic?

When we ask, “Why did the Russian opposition lose in 2011?” we ipso facto assume that it could have won had it made different decisions.

Among the alternate scenarios must often cited are if protesters had held an unsanctioned rally outside the Kremlin walls in place of the sanctioned gathering it did hold on Bolotnaya Square — on a strategically inconvenient island in the middle of the Moscow River — and if opposition leaders had not left town over the long New Year’s holiday.

But just for a change, maybe we should ask whether protesters ever had any chance at all of winning.

It now increasingly appears that they did not.

That possibility simply didn’t exist because Russian society was completely different 10 years ago. In 2009-2010, the largest rallies in Russia had brought together only 100-200 people — not counting a riot by violent nationalist football fans. What’s more, the great majority of people had no experience whatever of political action — with the possible exception of older citizens who had attended rallies during the collapse of the Soviet Union — and protest organizers had no experience providing legal assistance to detainees and financial assistance to individuals and organizations subjected to repression.

For today’s 20-year-olds in Russia, sending a donation of even a few dollars a month to help keep persecuted media outlets stay afloat and attending an unsanctioned rally is as natural as brushing your teeth. Ten years ago, this was all new.

At that time, civil society was just emerging in Russia. It was in its infancy, naive and overly optimistic.

Don’t let your eyes fool you, though. To a casual observer, it seems that little has changed between the Russia of 2011 and that of today. After all, opposition leader Alexei Navalny is behind bars, his organization has been disbanded, all independent media outlets have been branded with the onerous label of foreign agent and, once again, it seems that no one is stirring and all is quiet on the protest front.

This is not the case, however. There is a huge difference in today’s society. Ten years ago, politics was not even on the agenda.

Yes, many thousands of people took to the streets, but they did so with an underlying complacency. Now, politics is front and center. The fact that citizens’ political demands have been strangled and shoved under the carpet so as not to be an eyesore has only made people angrier.

Just imagine: in every major Russian city, there are now thousands of people with experience in direct political action, solidarity, donating to a cause and signing petitions. And if to include their friends, relatives and co-workers in the ranks of these “reserves”, the number is even larger. But most importantly, Russia has accumulated a great deal of emotional baggage, a sort of collective grievance with the authorities.

Yes, the Bolotnaya rallies failed. But they couldn’t have succeeded anyway because they were only the starting point. They served as the trigger for two things: the Kremlin’s aggressively repressive policy, but also as a kind of “civil society university”, an impulse to instruct countless members of the intelligentsia and middle class in the ways of political action. It’s like the “thesis and antithesis” of Hegel’s philosophy.

And no one knows what the ultimate “synthesis” will be.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.