In 1967, poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya penned her famous line: “Oh Strastnoy, when will you have seen enough demonstrators?” She was writing about a major rally on Pushkin Square in Moscow that year in protest at the Soviet show trial against writers Andrei Sinyavski and Yuli Daniel. The poem continues:

“And he, in cloak, in chains, bowing his curly head,

Is he still thinking about his ‘cruel century’?”

Of course, “he, in cloak” refers to the great Russian poet Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin. His “cruel century” turned out to be less cruel than the 20th — especially in Russia, where the 1960s saw the return of targeted repressions and Stalinism.

We see the same thing happening now.

Unlike the protest in response to the 1967 show trial, today’s landmark show of resistance was the large-scale protests against the falsification of parliamentary elections on Dec. 5, 2011. They happened 10 years ago, under the shadow of a monument to another Alexander Sergeyevich, this time Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov on Chistoprudny Boulevard.

Oh, the things that statue has witnessed since its installation in 1959, including the Soviet police cracking down on hippies gathered nearby. But no other Russian protest has been as impassioned as that one a decade ago.

Few people have noted the historic connection between the two demonstrations, although they happened in the shadows of statues to Pushkin and Griboyedov 46 years apart. The link, however, is both obvious and symbolic. Russia’s protest movement started on Strastnoy Boulevard and Pushkin Square, and reawakened there and on Chistoprudny Boulevard decades later.

The authorities patronizingly authorized only 500 people to gather at Chistye Prudy in 2011, but four times that number showed up. And those figures are based on police estimates that consistently report only half or a third of the actual total, meaning that as many as 6,000 protesters might have gathered that day.

That rally became the model for all that followed. Mobilizing participants through social media, huge masses of people taking to the streets and speeches by iconic figures from the opposition and civil society. It also saw riot police snatching individuals from the crowd, hauling them away in police wagons and jamming the protesters’ electronic communications.

On Dec. 5, 2011, a group of demonstrators became emboldened when they broke through a barrier near Lubyanka Square, and soon began yelling, “We are in power here!” Feeling that they were not simply members of a crowd, but fully-fledged citizens, many shouted, “This is our city!” Others joined in with, “Give us back our votes!” in a call to restore their stolen constitutional rights.

That rallying cry was heard again in Khabarovsk in 2020, during protests over the arrest of Governor Sergei Furgal, whom the people had chosen through unexpectedly fair elections.

The breakthrough in Russia’s protest movement that occurred 10 years ago eventually prompted the authorities to retaliate with numerous arrests, including those of opposition leaders Alexei Navalny and Ilya Yashin, and to hand down illegal, preordained court rulings that slapped protesters with 15-day jail sentences.

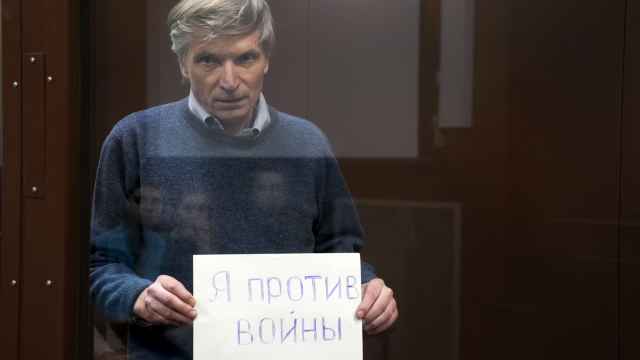

Police wagon, detention, courtroom, prison cell. This was the path the authorities prepared for every active and responsible citizen who fought for their constitutional rights, a path they and subsequent protesters were destined to follow for the next 10 years.

There were also acts of solidarity when those who were arrested — though holding very different convictions — felt united as victims of state-sponsored abuse of power. But that cohesiveness had not yet gelled into a clearly formulated “I am you and you are me” conviction.

Russian protesters felt a certain connection to the increasingly frequent protests in the West, just as protests in the West in 1968 against oppressive forces became intertwined with the Prague Spring the same year. The street camps of civil activists that emerged spontaneously in Moscow in May 2012 after the inauguration of President Vladimir Putin also appeared on Chistoprudny Boulevard around the monument to Kazakh poet Abai Kunanbayev, giving them the nickname Occupy Abai, in the spirit of the Occupy Wall Street movement.

But before that, there were major rallies on Bolotnaya Square and Sakharov Avenue in Moscow, and also in other Russian cities including St. Petersburg. The most impressive and unusual for Moscow, mired as it is in sleepy and cynical prosperity, were the demonstrations on Dec. 5 and 10, 2011, and Feb. 4, 2012.

This gave rise to completely new feelings of unity and the belief that change was possible. The authorities responded with a tactic they would come to employ frequently — pro-Putin rallies by state employees dependent for their livelihoods on government coffers.

Kremlin propaganda tried to portray the Muscovites taking to the streets as rich, a claim that did survive even a cursory glance at the crowds. The term “creative class” — first coined by American urban studies theorist Richard Florida to denote people in the creative professions — was applied to the protesters for no apparent reason. But even the infamous chief Kremlin ideologist Vladislav Surkov referred to the protesters as “angry townspeople.”

Exactly as American sociologist Seymour Lipset had theorized, a well-developed, urbanized segment of society had risen to demand political rights and democracy. For the first time in many years, the crowd truly felt like a civil movement that could overcome rulers’ authoritarian tendencies and resolve the crisis of representation provoked by electoral fraud.

This seemed to have knocked the authorities into a stupor. Even the Kremlin-backed liberal Alexei Kudrin began making appearances in public squares amid rumors he had persuaded Putin to negotiate with representatives of civil society. Putin took a break until the New Year holidays, and later extended it. His campaign was ostensibly focused on the middle class, but civil society held no illusions, responding to his inauguration with a large-scale rally that was brutally suppressed and accompanied by criminal charges against a number of protesters.

Immediately after the elections, the newly re-elected Putin stepped up repressive measures and further hardened state ideology and propaganda. The protest movement, which had attempted to institutionalize itself in the form of a Coordinating Council, became mired in controversy.

However, the protest mood itself did not wane, and in subsequent years became focused on Alexei Navalny. In 2020-2021, the authorities solved this problem by openly and shamelessly ramping up repression by both the police and the legislature.

Deprived of its leaders, denied success and demoralized, the opposition and civil society have finally given up the outward fight, but continue on like an underground fire that, sparked by any chance event, could ignite. Another sign of people’s dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs is that more non-communists voted for communists in the 2021 elections than ever before.

The story of the civil protest movement for the restoration of constitutional rights has not ended. It will continue, even if the new protesters don't know or remember anything of what happened in the shadow of the Pushkin monument in the second half of the 1960s -and in the shadow of Griboyedov 10 years ago.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.