SENNOY, Krasnodar Region — Amid the deep coves and narrow crevices that honeycomb this part of Russia’s Black Sea coast, archaeologists have for eighty years chipped away at one of Europe’s richest historical treasure troves.

Ever since Russia conquered the Taman peninsula — a hilly, lagoon-studded spur of land that faces annexed Crimea across the Kerch Strait — in 1828, scholars have puzzled over how Phanagoria, the dynamic Ancient Greek colony it housed, could have thrived for almost two millennia before vanishing almost without trace.

“You can find grand stone cities anywhere on the Mediterranean,” said Vladimir Kuznetsov, a 68-year-old archaeologist who has been working on the site since 1978. “But what we have at Phanagoria is different.”

Situated outside the small village of Sennoy, Phanagoria, now one of Russia’s best-resourced and highest-profile digs, shines a light not just on the region’s long-lost Ancient Greek heritage, but also on how Russian archaeologists have had to adapt to a difficult financial environment with limited state support.

Though archaeologists have been working at Phanagoria on and off since 1936, few of the site’s recent finds would ever have been made, were it not for a chance — and very Russian — twist of fate.

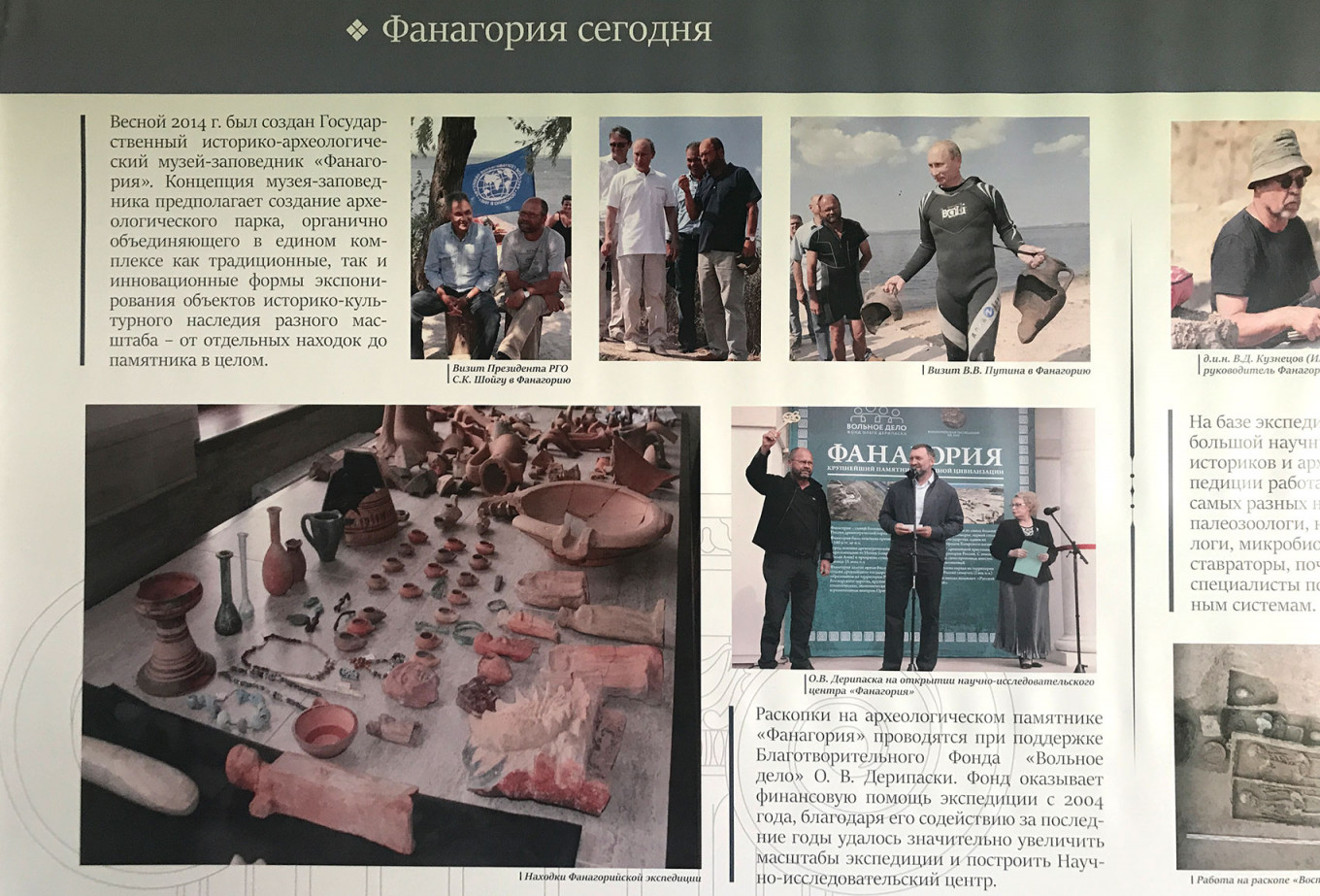

In 2004, billionaire industrialist Oleg Deripaska — owner of the RusAl aluminium company and a native of the local Krasnodar region who owns a home a few hours’ drive from Phanagoria — began financing the excavations. His Volnoe Delo charitable foundation has so far donated $16.4 million to the project.

Archeological dream come true

Strung out along a remote, uninhabited stretch of a slender cove that burrows its way into the peninsula, rising seas and shifting dunes have buried ancient Phanagoria under an unusually thick layer of sand and swamps.

For professional archaeologists — whose work is often obstructed by modern structures — it’s a scientific dream come true.

“The archaeological layer here runs six metres deep, with each era in the city’s history preserved on top of the last. It’s very rare to have a layer so deep,” said Kuznetsov.

Nestled as it is today between the budget resort villages of the Black Sea riviera and the hypersensitive military bottleneck of the Kerch Strait, it is hard to imagine that the Taman peninsula was once a thriving commercial hub.

However, Phanagoria, a Greek colony founded around 543 BC by refugees from the Persian conquest of Anatolia, grew into a prosperous city-state on the back of trade with the Scythian tribes of what is now Ukraine.

Though only around two percent of the Phanagoria site has been excavated, finds already testify to a wealthy and powerful settlement, passed down through the succession of empires that have dominated Russia’s southern steppe.

There’s the fragment of marble wall engraved with Persian cuneiform text, the only one of its kind ever found outside the former Persian Empire. The menorah-engraved tombstones, evidence that the faith of the Khazars — a tribe of Turkic nomads who converted to Judaism in the first millennium — was present in this part of Russia. Or its Christian diocese, Russia’s oldest, which predates the conversion of Kievan Rus to Christianity by almost 500 years.

Phanagoria’s sudden extinction, around the year 1000, remains an archaeological mystery. Historians say a letter discovered in a Cairo archive in the late nineteenth century may hint that early Russian invaders from the north were responsible.

Though archaeology has never been chief among rich Russians’ charitable causes, a string of bespoke archaeological funds help wealthy Russians support digs.

Deripaska’s support of Phanagoria, however, makes him the single biggest donor to archaeological causes in Russia, and Phanagoria by far the country’s best-financed dig.

“For rich Russians, supporting archaeology is a lot like supporting artistic causes,” said Elisabeth Schimpfossl, a senior lecturer at the U.K.’s Aston University and author of a book on rich Russians and their philanthropic habits.

“It’s often about filling in gaps where state provision is lacking.”

Though individual philanthropy plays a major role in archaeology all around the world, in Russia — where government grants for the field are rare to non-existent — private largesse has assumed particular importance.

“In Russia, there is no direct state aid for archaeology,” said Anastasia Stoyanova, an archaeologist and head of Millenium Legacy, a charitable fund supporting digs in Crimea.

“There are a few indirect grants but it’s almost impossible to actually get one, and they don’t provide the long-term, year-on-year support you need for a serious project, anyway.”

In the absence of meaningful state subsidies, many Russian archaeological projects are financed by so-called “rescue archaeology,” or commercial contracts to excavate construction sites.

With developers legally required to pay to excavate lands they plan to build on, Russian archaeologists are often forced to recycle their private earnings from commercial work to support their academic projects themselves.

With the broader field’s funding tenuous, Phanagoria has emerged as a lavishly resourced outlier, even as much of the rest of Russia’s archaeological heritage remains underexplored and at risk.

“In general, the outlook for archaeology in Russia isn’t great,” said Stoyanova.

“There are a handful of sites like Phanagoria, which are very well provided for. But apart from that, the situation is tough.”

For Kuznetsov, who recalls working on the Phanagoria site with only his wife during the economic crisis of the 1990s when funding for archaeology withered away, financing from Deripaska — who has been sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department — has been transformational.

“Not having to worry about your funding does give you a certain freedom,” he said.

Further Discoveries

On the walls of Phanagoria’s luxurious, Deripaska-built visitors’ complex hang photographs of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Defense Minister Sergei Shoygu, both of whom have visited the excavations.

Out on the site, the results of the site’s lavish funding are even clearer. Its financing guaranteed, Phanagoria has been able to attract an expansive team of scholars, including numismatists to study the city’s coinage, and anthropologists to reconstruct its everyday life.

Analysis of human remains found at the site has enabled the project to make groundbreaking discoveries, including determining an ancient Phanagorian’s life expectancy — 38 years — and to identify the parasites that likely inhabited their bodies.

“Without exaggeration, I honestly don’t think there’s a team like ours anywhere else in Russia,” said Kuznetsov.

Now, a vast new museum complex is planned to cater for Russian tourists travelling to annexed Crimea on the newly built bridge, which spans the Kerch Strait within view of Phanagoria.

For Kuznetsov and his team, however, the focus remains on excavating the as-yet-untouched remainder of the 65-hectare site.

One story, of the deposed Byzantine emperor Justinian II who was reputedly exiled to Phanagoria at the turn of the eighth century, has spurred many to wonder what else might be hidden beneath the peninsula’s rolling hills.

“If a Byzantine emperor lived here, you’d assume he had a palace,” said Kuznetsov, gesturing toward the gentle, grassy slopes around the digsite.

“I just don’t know where it is yet.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.