“We need to work with what we have,” said economist and regional studies expert Natalia Zubarevich at last week’s launch of Russia 2050: Utopia, Prognoses, a compilation of fascinating essays, art, and short fiction exploring visions of Russia’s future.

Visions is the key word here — social scientists are often pestered for predictions, but it is a notoriously thankless task, and much more so given the perpetual flux of Russian history. That is why the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung foundation, which produced the anthology, asked its contributors for visions not just of what they expected to happen, but what they wanted to see.

As Russia enters a fourth Covid-19 wave, and foreign agent laws stifle the media, it’s understandably difficult to imagine the future. But paradoxically, even as the weight of repression restricts political life to the margins, the same pressure cooker belies a vibrant collective imagination that looks forward.

What we get in this 600-page book is akin to a new age architectural space. With young architects among the contributors, it’s an indelible component of any musings on the future. It presents dystopia meeting utopia, cyberpunk mingling with the rise of the Russian Orthodox Church and security — according to one of the essays by Yekaterina Schulmann — becoming a religion.

A short story by the novelist Oleg Zobern describes an exorcism set in a world where the premier learning establishment is something called the Imperial Academy of Cybercontrol Workers, where sexual propositioning by random men riding hoverboards is not only sanctioned but encouraged, and yet the Church remains the supreme arbiter and the only institution allowed to have food markets in a city populated by pneumatic food delivery systems. Zobern’s Russia is, of course, a monarchy.

In the essays and fiction, the positive visions that contributors were asked to come up with mingle with the grotesque. In the same way that a mix of all the colors of the rainbow yields white, so the meandering cataclysms, catastrophes and possibilities in the next 30 years swirl together to give, unexpectedly, a sense of hope.

There is also sober analysis, including an essay titled “Russia After Putin” by Dmitry Travin suggesting that inter-elite tensions that follow Vladimir Putin will likely lead, if not to democracy, then at the very least to the abandonment of the Kremlin’s current besieged-fortress ideology.

And there is debate — one of the book’s features is arrows in the margins indicating that the idea in a given passage is either developed further or contested by another author, with a page number.

The very fact that this book was possible — and that its creators chose the idea of looking forward after initially planning a book about Russia’s past — suggests that even in the current political climate, society is looking to the future, and no longer to the past. It may not necessarily be a rosy one, but it is one that works with what Russia currently has, a pragmatic, interests-oriented practical approach that also makes room for spiritual reckoning with historical trauma.

This idea is not new. Several years ago, when interviewing opposition activists from both liberal and nationalist groups, I stumbled upon an unexpected attitude: “We’re not thinking about how to end Putinism,” one politician said to me. “We are thinking about how we will work after he is gone.”

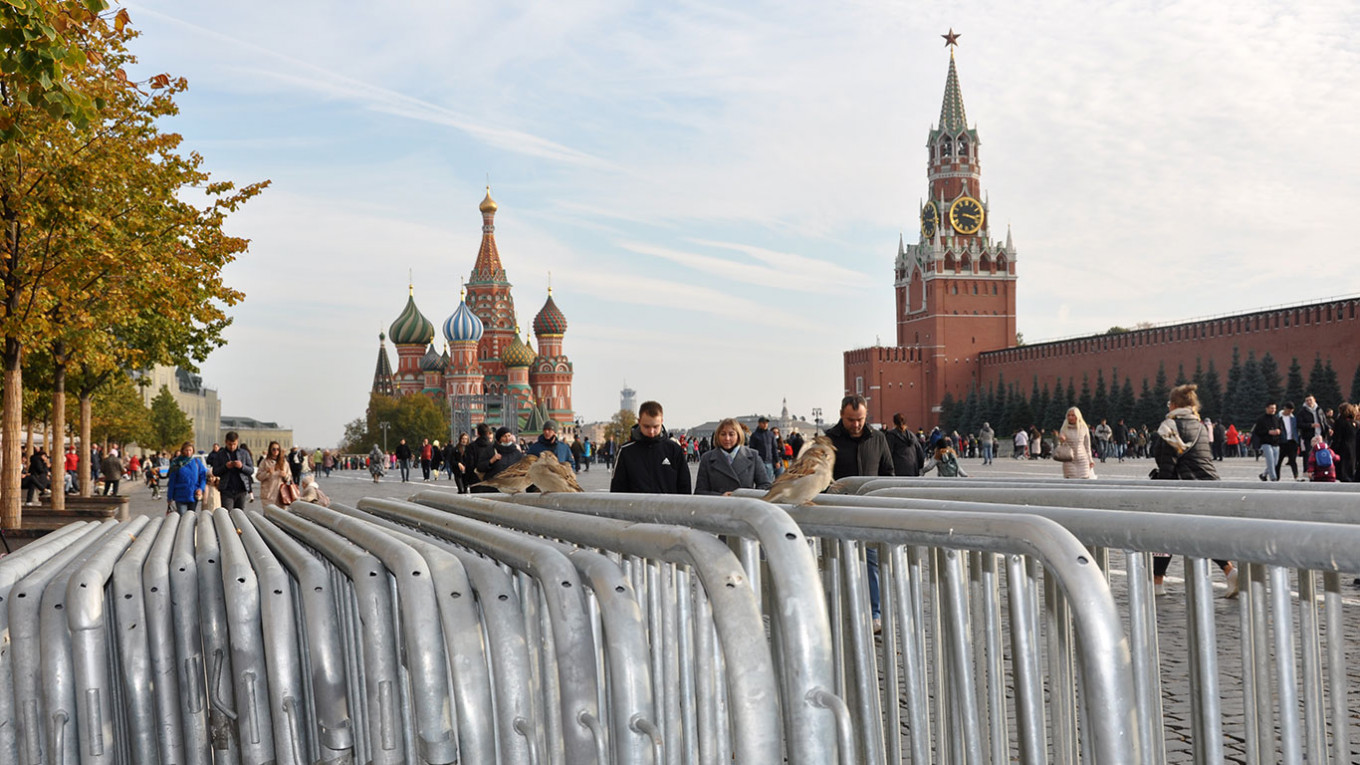

This may be why the most successful protest rallies in recent years revolved around specific, local interests – defending a city square in Yekaterinburg, or rescuing a framed journalist in Moscow.

Tangible future

So, what will that future look like? Will we see an aging population, one serviced by domestic cleaning and food preparation robots? Will we see a network of high-speed railways connecting Russia, encouraging the growth of metropolises and solving the perennial problem of its vast expanse and social incohesion? Will we see a benign monarchy, or at least a hybrid authoritarianism that is neither repressive nor kleptocratic, but humane, pragmatic, and practical? Will there be a thaw after the looming winter?

Possibly. But as Zubarevich suggests, looking to the future means building on what one already has. That means that the vibrant discussions about what Russia will look like in 30 years — of which this book was only a cross-section — are founded on a stark, ongoing assessment and reflection of how Russians live today. That makes a future not just possible, but tangible.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.