The Museum of Russian Impressionism in Moscow has once again organized a show of little-known but fascinating Russian art.

“Other Shores” is a partial reconstruction of an almost forgotten exhibition held almost 100 years ago in New York, in 1924. The exhibition included works by Petr Konchalvsky, Igor Grabar, Mikhail Lariononv, Aristarkh Lentulov, Boris Grigoriev, and Stanislav Zhukovsky. At the entrance to the show visitors are greeted by black and white photographs flashing images of ladies in feathers, Anna Pavlova in a tutu, Fyodor Chaliapin in a dressing gown, dirigibles floating over the Manhattan skyscrapers and Buster Keaton dashing after his automobile.

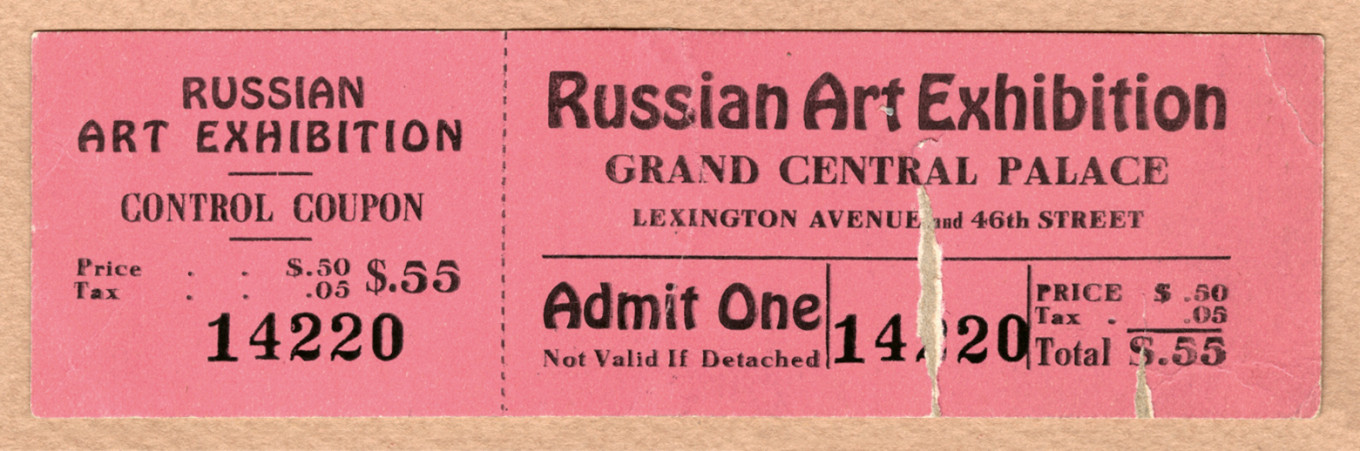

The name “Other Shores” refers to the autobiography by one of the greatest Russian writers in emigration, Vladimir Nabokov. The 1924 show had a different name: It was called the Russian Art Exhibition and was advertised with posters of a bearded merchant in a warm, bright blue homespun coat based on a painting by Boris Kustodiev.

The show is filled with masterpieces of Russian art that had become completely unknown in Russia, such as Konstantin Somov’s “Old Ballet” (1923) painted a year before the exhibition. It might have been chosen by the curators of that distant show as an allegory of pre-Revolutionary Russia. After all, ballet was the embodiment of all the glory and power of the empire, the quintessence of the luxury that the Russian court was famous for. Two small porcelain statuettes by the same artist — “A Lady Removing Her Mask” and “Lovers” — are some of the show’s best works despite their small size.

Forgotten masterpieces

Seven works by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin were sent to New York, most of them portraits, including one of Anna Akhmatova, a family portrait and one painting of his wife. The exhibition includes Petrov-Vodkin's “Yellow Face” (1921), which was sent to Moscow from the Chuvash State Art Museum.

Another fine work is “Officer’s Barber” by Mikhail Larionov that is now in the collection of the Albertina Museum in Vienna. Done in the “neo-primitivist period of the artist, when he was inspired by provincial Russian signs,” the catalog notes, it is brilliantly colorful and comedic.

The vivid painting “Young Peasant Woman” (1920) by Abram Arkhipov had a curious fate. It was purchased during the tour by the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans, which then passed it on to what is now the Art Museum of News Orleans. It remained there until 2008 when it was sold to a private collector at an auction at Christie’s.

The museum curator and exhibition specialists wanted to recreate the chronicle of events and find all the works that represented distant Russia — then already Soviet Russia — to the American public. But the show had little “Soviet art.” The paintings reflected the spirit of the recent past or the 1920s.

Great artists, bad businessmen

The exhibition that crossed almost all of prosperous America was organized by the painters themselves — Igor Grabar, Sergei Vinogradov, and Konstantin Somov — and not without a certain dose of opportunism. The chance to show their works in America seemed like salvation to artists in dire straits after the 1917 Revolution. They invited about one hundred of the best artists in the country, including Martiros Saryan,Anna Golubkina, Konstantin Yuon, Isaak Brodsky and Stanislav Zhukovsky. More than one thousand works of art were packed and sent by ship to the U.S. They were chosen as works for every taste, from the Wanderers to scandalous avant-garde artists, from gloomy views of the outskirts of St. Petersburg to the erotic “Book of the Marquess.”

When the Russian artists arrived in New York, they were completely bowled over by the city: skyscrapers — “new Cologne cathedrals” — a sea of lights, the sounds of jazz. It was all new and unfamiliar to them. “America is not at all like Europe, it’s a completely different country,” Sergei Vinogradov wrote home.

As the notes to the exhibition explain, “The artists didn’t have the goal of making their mark in the history of Russian-American relations: they were busy with more down-to-earth tasks and weren’t trying to capture it all on paper and canvas. They undoubtedly could not imagine that 100 years from then people would be studying this lark as something serious.”

Although at the time the U.S. government had not recognized the Soviet Union, the artists from Russia were greeted quite warmly by the press and public. After the show in New York, the exhibition went on tour around the country and was even sent north to Canada. In the end, the organizers had a loss of more than $15,000 due to their ignorance of American life, inflated expectations, and the steep prices set by the artists. In January 1927 the exhibition returned to Russia.

Take the exhibition with you

At the end of this show is a marvelous catalog that allows you to see the detailed graphics up close. They are worth looking at, especially works by Vasily Masyutin with his expressive portraits of his contemporaries, and book covers done by Dmitri Mitrokhin. Unfortunately, the dim lighting in the show, designed to be expressive, sometimes makes it difficult to see all the works well. In one dark corner is a double watercolor portrait of the daughters of the opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin, Marfa and Marina, paintedby Boris Kustodiev in 1920. The catalog brings it to life.

The catalog also includes works that were sent to New York in 1924 but not available for display in the show. One of these works is a painting by Ilya Mashkov called “Russian Venus” (1914) that depicts a nude Russian beauty lying in front of an enormous painting of Napoleon on a troika, galloping with his troops across the Russian fields.

The show will run until Jan. 16, 2022. For more information and ticket sales, see the site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.