ULYANOVSK - When Airat Gibatdinov was born in 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev’s Perestroika had already set the Soviet Union on its path to oblivion.

But now, the local lawmaker and deputy head of Russia’s revived Communist Party in Ulyanovsk — the Volga riverside hometown of the U.S.S.R.’s founding father Vladimir Lenin — has dedicated his life to resurrecting a Soviet socialism he barely remembers.

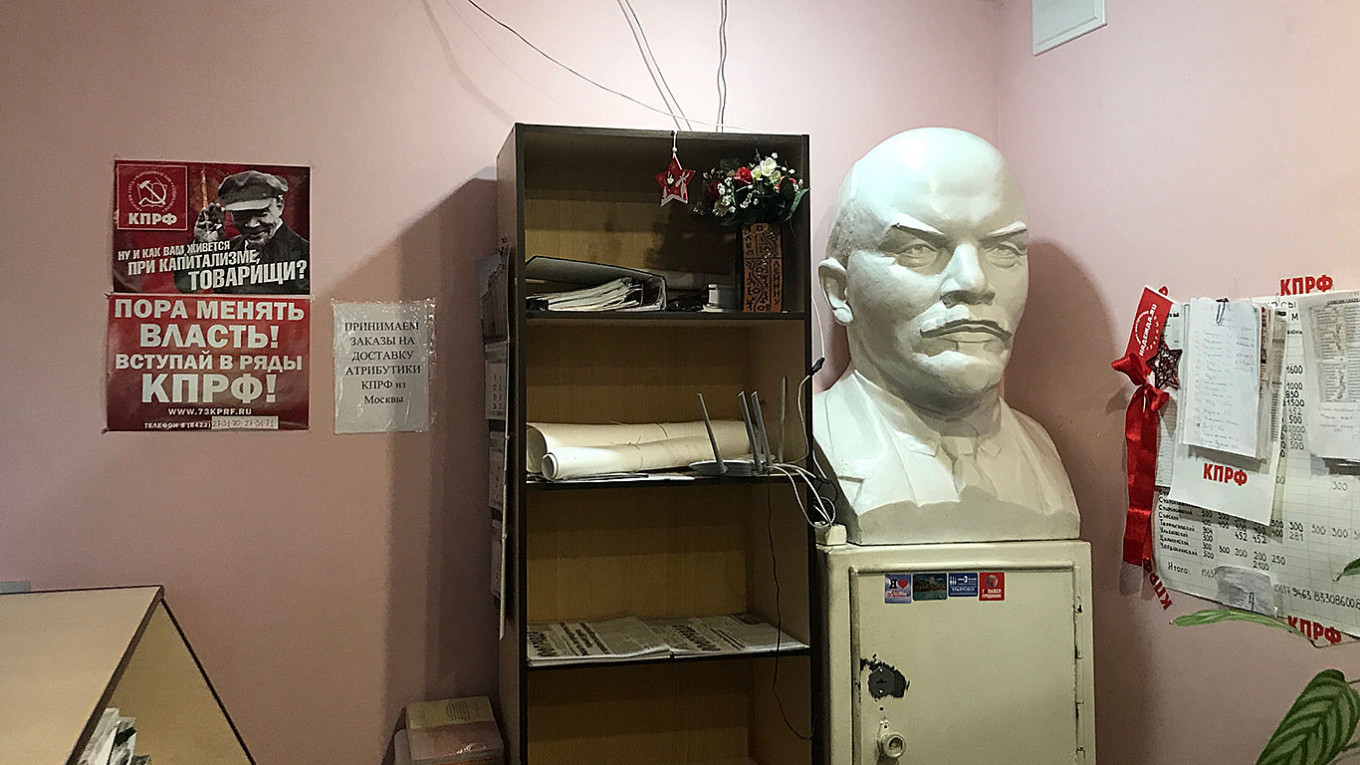

“We are the only party that fights for the working class,” said Gibatdinov in an interview at the Russian Communist Party’s Ulyanovsk headquarters, an unassuming warren of offices decked with red flags and Lenin portraits sandwiched between a high-end coffee joint and a hookah bar.

“I hope we’ll see a new Russian socialism in my lifetime.”

Though widely considered part of the tame, Kremlin-loyal “systemic” opposition, the Communist Party (KPRF) — still the country’s second largest political organization — has seen a modest uptick in its support ahead of parliamentary elections in September.

With the pro-Kremlin’s United Russia bloc’s polling sinking to historic lows ahead of the vote for the Duma lower house of parliament, the Communists are hoping to turn popular discontent over falling living standards into a strong showing at the polls, including in cities like Ulyanovsk.

Once the leading opposition to Boris Yeltsin’s free market reforms in the 1990s, the KPRF has long since become part of Russia’s political establishment.

Though the party’s first, and so far only leader, Gennady Zyuganov only narrowly lost to Yeltsin in the 1996 presidential election, over the past two decades he has taken a more loyalist direction, offering rhetorical opposition to the Kremlin while remaining broadly supportive of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

It’s a shift that has been accompanied by a steady decline in the party’s national standing.

Once the country’s largest single political force with broad nationwide support, the Communists now rely on an aging, Soviet nostalgic voter base of between 10 and 15%, concentrated in a handful of strongholds.

Ulyanovsk, a city of 600,000 that spans a picturesque bend in the Volga river 400 miles east of Moscow, is one of them.

Previously known as Simbirsk, Ulyanovsk has for almost a century borne the name of its most famous son, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov — better known as Lenin.

Even though this increasingly prosperous provincial center today bears little resemblance to the quiet backwater where Lenin was born in 1870, and left, never to return, at seventeen, the Bolshevik leader remains a ubiquitous presence in Ulyanovsk.

In the city center, a string of sprawling museum complexes commemorate the life and achievements of Lenin, and his steely-eyed visage adorns craft beer bars catering to Ulyanovsk’s student population.

On the main square, Ulyanovsk State Pedagogical University bears the name of Lenin’s father Ilya Ulyanov, a provincial school inspector who died when the future revolutionary leader was sixteen.

For Ulyanovsk’s communists, their city’s link with the revered Soviet founder is a source of continued pride.

“The one thing everyone knows about Ulyanovsk is that it’s where Vladimir Iliych Lenin was born,” said Gibatdinov, using Lenin’s patronymic as a sign of respect.

“Even though they don’t teach the history of Lenin and the revolution properly anymore, something has remained in our mentality. People here have a very strong sense of fairness.”

It’s a revolutionary heritage that lives on even three decades after the Soviet Union collapsed. At the last parliamentary election in 2016, Ulyanovsk was one of a handful of cities where the KPRF defeated United Russia to win the local Duma district.

But Ulyanovsk is also a microcosm of the wider dilemmas facing Russia’s modern communists, who must reconcile a revolutionary ideology with their status as a “systemic” pillar of the political establishment.

The city’s State Duma deputy Alexei Kurinny is a relative radical within the KPRF who publicly praised jailed Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny’s “personal bravery” on his return to Russia in January.

By contrast, the region’s communist governor, Alexei Russkikh — appointed by Putin in April after his unpopular United Russia predecessor was fired — is widely seen as Kremlin-loyal, and his nomination a reward for the party leadership’s continued cooperation with the authorities.

“The communists are a very complex, divided party,” said Tatiana Stanovaya, founder of R.Politik, a political consultancy. “The senior cadres understand what they have to lose and play by the Kremlin’s rules.”

“But many of the younger officials in the regions want a more confrontational approach to the authorities.”

Today, there are signs that the Communists’ comfortable coexistence with the Kremlin may be coming to an end.

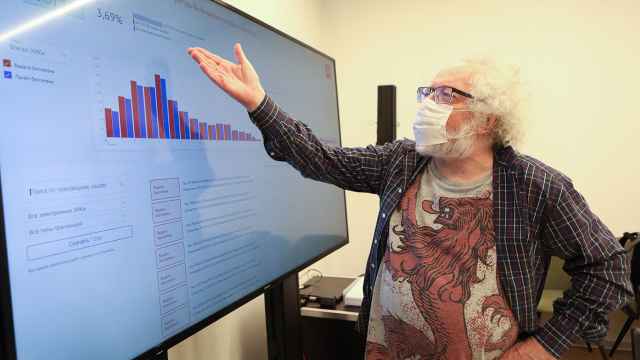

Even as polls show the KPRF set to almost double its 2016 vote share amid anxieties around sliding incomes and an eroding social safety net, the authorities have denied a string of high-profile communists registration as candidates.

In July, Pavel Grudinin — an agribusiness magnate who came second to Putin in the 2018 presidential election — was barred from running for parliament in September.

Though Grudinin was formally banned for having failed to properly disclose overseas investments, many communists, including Grudinin himself, saw it as a politically-motivated move against a popular and independent-minded candidate.

It was a story repeated throughout the lead-up to the polls, with would-be communist candidates including Saratov regional deputy and popular videoblogger Nikolai Bondarenko and influential Moscow party boss Valery Rashkin threatened with exclusions of their own.

For many in the party, the wave of bans is aimed at quashing a defiant atmosphere in parts of the KPRF increasingly unwilling to toe the Kremlin’s line.

“The mood in the party is getting more radical,” said Yevgeny Stupin, a Communist Moscow City Duma deputy who has been facing efforts to strip him of his office after he attended protests in support of Navalny in the winter.

“United Russia’s ratings are low enough that they need to disqualify us to have a chance of winning.”

Though critics say Russian elections have rarely been free or fair in recent years, “systemic” opposition parties have at least been able to win from time to time.

But with controversial new electronic and early voting schemes that some fear will make falsification easier than ever, opposition-minded communists increasingly doubt that victory is possible, regardless of public opinion.

“Given what’s happening at the federal level, with early voting, electronic voting, it’s becoming more difficult for us,” said Gibatdinov, who is running for the Duma in an Ulyanovsk region district.

“Of course, they can just rig it.”

But above all, candidates of all stripes must contend with deep-seated apathy among the Russian electorate.

A recent survey by Kremlin-linked pollster VTsIOM put interest in politics at a seventeen-year low only six weeks from election day.

At Ulyanovsk’s various Lenin shrines, there is a steady stream of visitors but little evidence of revolutionary zeal ahead of the polls.

“We’re very far from politics here,” said Olga Shaleva, a tour guide at the city’s Lenin House-Museum, the restored mansion in which the young Vladimir Ulyanov spent his early years.

“People visit our museum out of interest in history, not political beliefs.”

According to some experts, a low turnout in September could play into United Russia’s hands.

Though the ruling party’s polling remains mired below 30% amid corruption scandals and fallout from an unpopular 2018 pension reform, it is still much higher than any other party, with the second place KPRF attracting only 16%.

If turnout is as low as expected, United Russia is likely to retain its two-thirds majority in the State Duma, even with a much reduced vote.

“The Kremlin wants the elections to be as boring as possible,” said political analyst Stanovaya.

“It’s in their interests that turnout is low, and that opposition-minded voters stay at home.”

But for the city’s communist stalwarts, despite voter apathy, fraudulent elections and the Kremlin’s screw tightening, elections are still worth contesting, even in an ever more undemocratic Russia.

“The people have been brainwashed against us for years.” said Gibatdinov. “It may be difficult, but we can still win.”

“The leftward turn is inevitable.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.