When State Duma deputy Oleg Shein runs for re-election later this month, he will do so without any expectation that the government might change, his party might win, or even that the vote itself will be clean.

“Obviously elections in Russia are very far from being fair,” said Shein, who represents the southern city of Astrakhan as a member of the center-left Kremlin-loyal A Just Russia party. “We constantly encounter rigging and falsification by the authorities.”

“But this is our path. It’s our country and we have no other choice.”

It’s a dilemma common to many members of Russia’s “systemic opposition” — the patchwork of tame parties allowed to compete on the country’s uneven electoral playing field who are nevertheless coming under increasing pressure ahead of this month’s elections to Russia’s national parliament, the State Duma.

After Russian President Vladimir Putin came to power in 1999, his political strategists quickly set about turning a political arena that, under his predecessor Boris Yeltsin, had been raucous and anarchic, into something more streamlined and docile.

Parties like the Communists and the far-right Liberal Democratic Party — which had mounted serious bids for office in the 1990s – were won over by a much more authoritarian Kremlin that promised to safeguard their privileges, while largely locking them out of actual power.

Meanwhile, a bewildering array of entirely new parties, ranging from the ultranationalist Rodina to the social-democratic A Just Russia, were created from thin air by Kremlin-aligned political consultants.

Only rarely, however, would any of the opposition parties actually win elections, with media coverage and state-backing heavily in favor of the Kremlin’s United Russia bloc.

Under the guidance of the flamboyant political operative Vladislav Surkov, Russia’s ersatz politics grew into what Surkov in 2006 termed “sovereign democracy,” a system that would preserve an element of democratic legitimacy while ensuring power remained with the ruling circle.

For the players, the deal was clear. By toeing the line, refraining from radical opposition and accepting that the ruling party would almost always win they could secure comfortable positions near the summit of the Russian state.

It’s a system with parallels in other authoritarian regimes, where faux-opposition parties often give the illusion of competition in otherwise rigged elections.

Though Russian officials — including electoral commission chief Ella Pamfilova and the country’s foreign ministry — have stressed that elections remain democratic, some participants are less sure.

“It’s not that the parties are totally fake,” said Sergei Ivanov, a Duma deputy for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR) since 2003. “But they are beholden to the Kremlin, one way or another.”

“They’ve been filtered so that they don’t present a real challenge to the authorities. Only weak, obedient candidates are allowed to run.”

One result of the Duma being on such a tight leash has been widespread perception of the national parliament as a talking shop filled with corrupt time servers.

Data from the Levada Center, an independent pollster, places the Duma as the least popular political institution in the country, with disapproval hovering between 50 and 70%.

Elections to the chamber typically see low turnout, as anti-Kremlin voters see little to like in an unpopular institution and the parties represented in it.

It’s a perception shared even by some lawmakers.

“I can’t speak for all deputies, but there are people who are primarily interested in making money,” said the LDPR’s Ivanov.

“It’s a good place to be. You get a big salary, a car, a flat and you don’t have to work very hard.”

Patchwork of parties

But for those who make up the patchwork of systemic parties loyal — to varying extents — to Putin, elections are still worth contesting, even if they acknowledge that the chances of victory are slim to non-existent.

For some, the greatest draw is the ability to articulate political ideas otherwise marginalized in Russia’s tightly controlled state media.

“We don’t have real elections in Russia,” said Grigory Yavlinsky, founder of the liberal Yabloko party, which has not had parliamentary representation in two decades, but which is still widely considered part of the moderate, systemic opposition.

“But taking part at least gives you a chance to discuss your views, which is usually impossible.”

For others, playing along with a system centred around Vladimir Putin and his party for now is a long-term bet on future political change that will, hypothetically, leave lawmakers well-placed to influence the country’s trajectory.

“We understand perfectly that the government is making things very difficult for any kind of opposition right now,” said A Just Russia deputy Shein. “So we are trying to lay the foundations for a future in which people will be able to choose the governing party.”

“The Duma is a platform that we can use to try to shape an alternative political culture and eventually elect a left-wing government,” he said.

For many, however, Russia’s authoritarian drift has made the logic of systemic opposition — hypothetical or otherwise — outdated.

With the Kremlin introducing tighter controls on elections and cracking down on critics, members of the hitherto-safe systemic parties have come under the sort of pressure previously reserved for “non-systemic” jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny and his followers.

In 2020, Sergei Furgal, the LDPR governor of the Far Eastern Khabarovsk region, was arrested on old murder charges.

Having swept to power two years previously in an upset victory that reportedly shocked the Kremlin, his arrest was seen as a means of removing a popular, non-United Russia political figure.

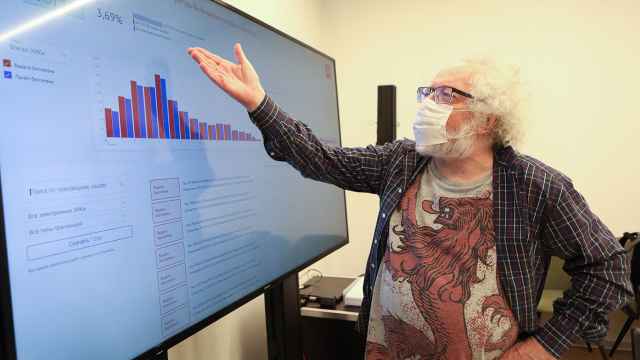

This year the Communists — traditionally Russia’s second largest and most independent-minded party — has been feeling the heat ahead of the Duma elections, with strong contenders including agribusiness magnate and former presidential candidate Pavel Grudinin barred from running.

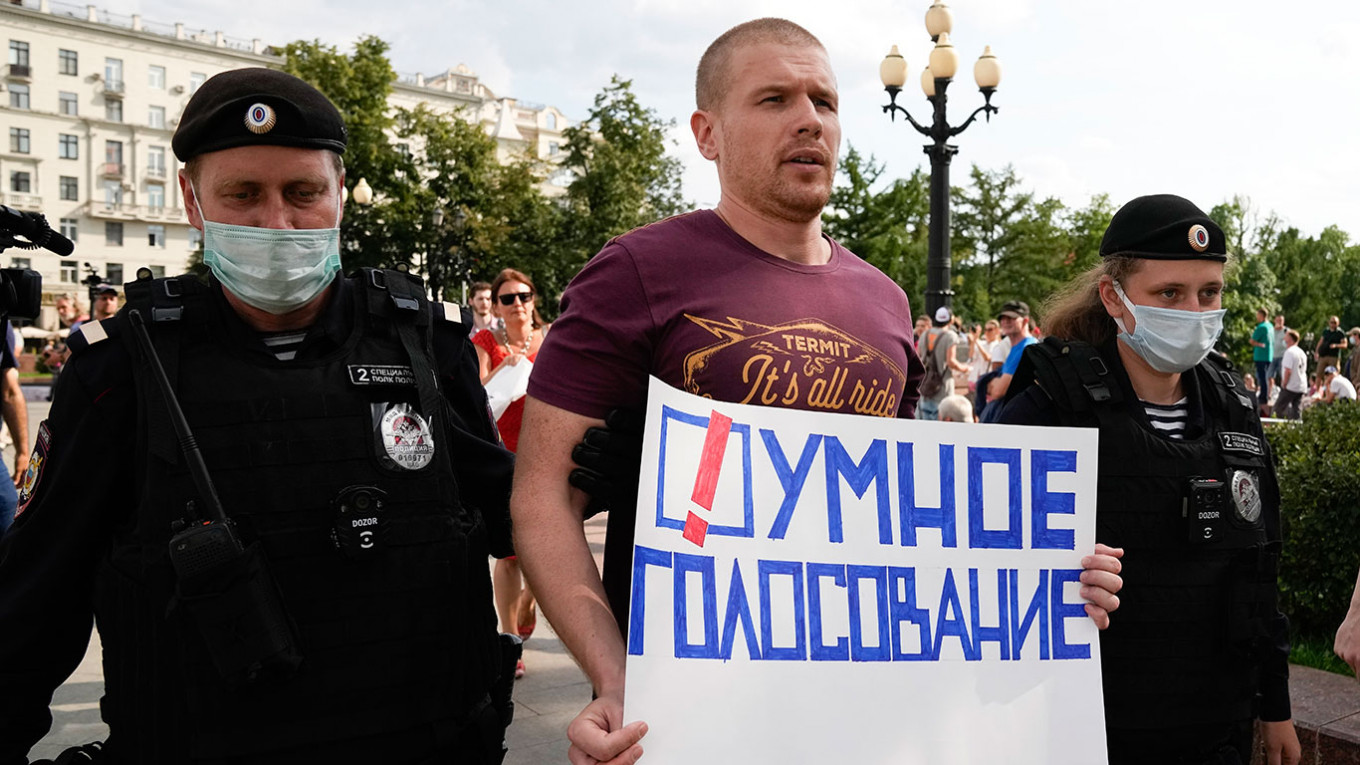

Some see the crackdown as a reaction to Navalny’s Smart Voting scheme, which seeks to weaponize the systemic parties by encouraging anti-Putin voters to rally behind the strongest available candidate.

As a result, some have left the ranks of the tame opposition altogether.

“Before the constitutional amendments were adopted, I still hoped that I could have a positive impact on the country,” said LDPR deputy Ivanov, referring to last year’s rewrite of Russia’s basic law that allows Putin to remain in office until 2036.

“But now I don’t see any point,” added Ivanov, who is not running for re-election in September.

“We have no ability to actually change anything.”

Ornamental role

It is a far cry from ten years ago when, in a case study in the fragility of Russia’s managed democracy, part of the systemic opposition looked ready to defect to a radical, anti-Kremlin street movement.

As demonstrations against election rigging erupted in the winter of 2011-12, several deputies from A Just Russia — founded in 2006 by Kremlin strategist Surkov as an explicitly Putin-loyal bloc — were among those to join the protests in Moscow.

Dmitry Gudkov, a State Duma deputy from 2011 to 2016 who rallied to the anti-Kremlin cause, told The Moscow Times there was no pretense at the time about the ultimate loyalties of his erstwhile party, from which he was later expelled.

“We were trying to transform A Just Russia,” said Gudkov in a telephone interview from Bulgaria, where he fled earlier this year, reportedly after being told he faced prison if he continued a campaign to retake his Duma seat.

“Obviously, it didn’t work out for us.”

But despite the defeats of recent years and the gloomy political outlook, participants in Russia’s pantomime politics still hold out hope that their ornamental role in the system might yet lead to future breakthroughs.

“For now we exist because the authorities need us as decorations,” said Yabloko founder Yavlinsky.

“But although we can't do much now, one day the wind might change. And we must keep our sails ready in case it does.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.