The relentless Russian offensive against global online platforms doesn’t show any sign of slowing down. That poses a question: Is Russia preparing to get rid of global platforms by the end of the year?

Such a development now seems highly likely, given the scale of the Russian import substitution effort in technology — a campaign which is much more important than learning how to produce Russian parmesan in the Moscow suburbs.

Only three years ago it had looked like a very distant and, frankly, hardly achievable objective.

At a tech conference in August 2019, the chief software engineer at one of the biggest Russian information security companies joked that they didn’t want to “miss the fun” of the panel on software import substitution. To them, the idea was little more than a not-so-clever joke. “That they put a Russian stamp on the box doesn’t mean that what’s inside is actually being made in the country.”

Nowadays he doesn’t joke as often.

Russia is now one of the very few countries in which local platforms are successfully competing with American online services. For years Russia has also boasted the most advanced online banking systems in Europe — more advanced even than in Japan. In short, the tech industry has been the fastest growing sector of the Russian economy — the result of having the largest engineering community in the world, inherited from the Soviet Union, along with a very good nationwide technical education system.

But until recently, a host of existential problems had persisted. Russia’s national Internet infrastructure was built on U.S. technology, mostly Cisco. That was a conscious decision made in the mid-1990s when local industry couldn’t provide the modern technology as it lagged the West’s by 20-25 years. Instead, in the span of three years, over 70% of all Russian intercity phone stations were replaced by modern digital ones, made in the West. Ever since the Russian Internet has been passed through and directed by American-made tech.

The country was also way behind the West in manufacturing hardware — especially microchips. There were several attempts in the 1990s and 2000s to breathe new life into the Soviet attempt to build a competitor to Silicon Valley in the town of Zelenograd, 25 miles from Moscow. All of them ended in disaster. Russian software engineers could design a good product, but mostly at low scale. When processing huge amounts of data was required, as with large database management systems, they were usually run at a loss. Even the FSB was forced to run its terrorist database on the American-made Oracle platform.

Russian social media platforms have long been the most popular inside the country, but WhatsApp had made a dramatic breakthrough thanks to the groups feature — something Russian schoolteachers and apartment building communities fell in love with — while most Russians watched YouTube, and Microsoft Office was omnipresent in offices all over the country.

That was the state of play six years ago, when import substitution was proclaimed one of the Kremlin’s major policy goals. Since then, Russia and its tech industry have come far.

Communications watchdog Roskomnadzor has been busy supplying the national internet infrastructure with hardware to underpin the so-called “Sovereign Internet” — Russian-made and paid by the government. Meanwhile the Trade Ministry is twisting the arms of software developers with Russian offices, like 1C and Parus, to adapt their products to Russian-made processors. The government’s target is to have 70% of all its technology purchases based on domestic-built processors by 2023. To help hit the goal, state development corporation Vnesheconombank was made to take over a chip plant in Zelenograd to restart its manufacturing facilities.

The government is also pushing hard to make MyOffice — software produced by a company partly owned by Kaspersky Lab — the default package on laptops and computers, replacing Microsoft Office. Simultaneously, the Digital Development Ministry is working on legislation to require all schools, health systems, and government officials to move to a government-supported “working communications platform,” consisting of Russian-made software for email, messaging and video calls. The Education Ministry, in turn, is developing its own guidelines to force teachers to communicate with students and parents through Russian-made messengers only. That would be a big blow to the popularity of WhatsApp and Zoom.

Where Russian-made solutions simply don’t exist, the Kremlin is content to go down the open-source route. For instance, it is pushing government-controlled corporations and ministries to ditch Oracle and start using solutions built on the PostgresQL database management system. While not a Russian product — it was developed at the University of California — it is widely believed that as open-source technology, it would be immune to Western sanctions.

And of course, the Kremlin has ensured that YouTube is facing new competition from Russian platforms. In 2019, Yandex launched its video service and Rutube has recently been reinvented with fresh funding provided by Gazprom Media and led by Alexander Zharov, a former head of Roskomnadzor.

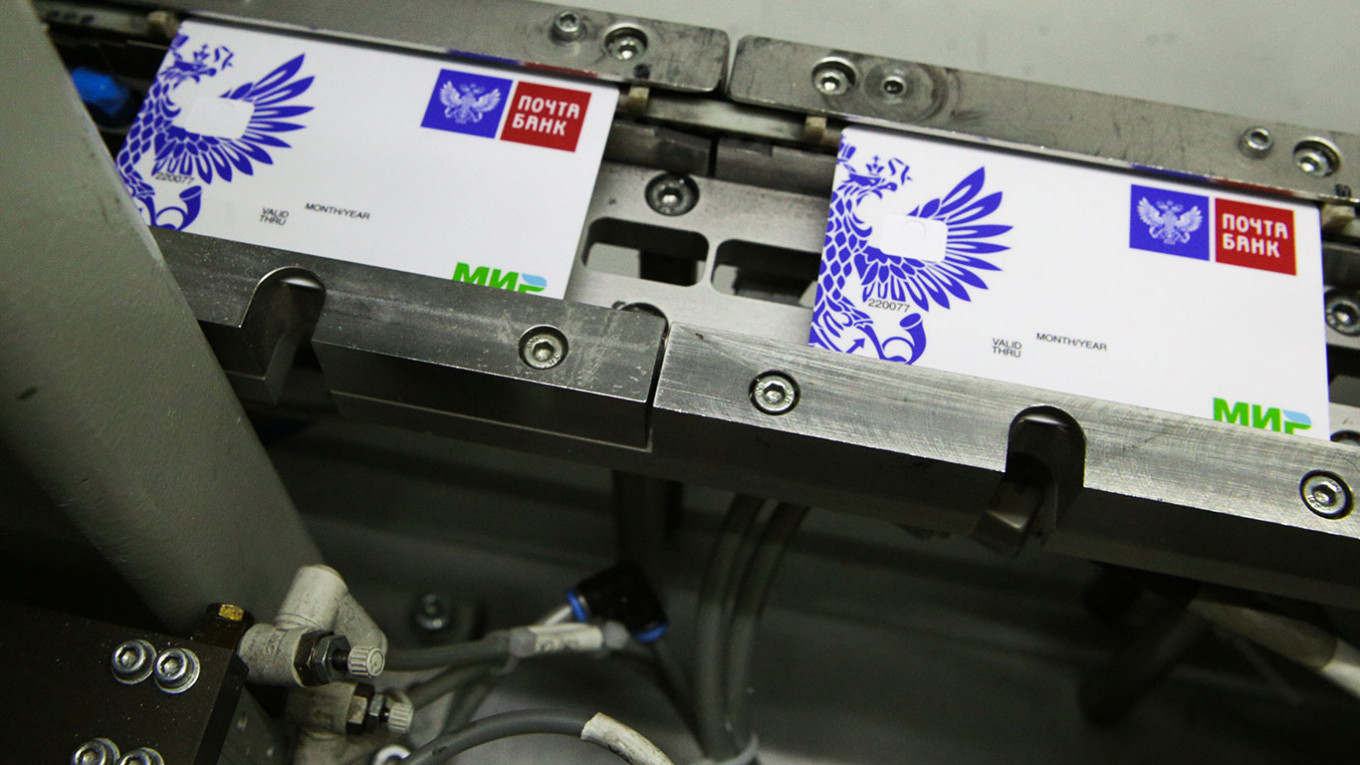

The impact of this large-scale effort is already visible. Last week the Skolkovo innovation center proudly reported the results of its research on the usage of credit cards in Russia. The national Mir card — operated by the Russian National Card Payment System and launched as a counter Western sanctions measure — has overtaken Visa and Mastercard as the top card provider in the country, being used by 42% of Russians. While many Mir clients were not offered a choice — they were given cards as part of their pension packages — its popularity is a reality.

The methods the Kremlin is employing to force Russians to adopt Russian-made technology might be primitive, but they are effective, and the government is making steady progress in dragging people into a domestic digital bubble, with very visible borders.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.