This summer the AZ Museum, a private museum dedicated to the works of Anatoly Zverev and non-conformist Soviet artists, has been celebrating the art of portraiture. The three-story townhouse museum has on display 70 works by “unofficial” Soviet and contemporary artists, that is, artists who did not work according to the conventions of socialist realism and their contemporary artistic descendants.

The name of the show defies easy translation. It is a show of “mugs” (animal and inhuman human faces); iconic images (faces of saints and holy people as painted on icons); and faces (portraits of people). As the helpful guide to the exhibition points out, perhaps the first images humans drew were animals —illustrations, doodles or magical totems. Then for centuries artists created ritualized faces on icons and in religious or ceremonial art where the gestures, poses, clothing, objects, entourage and colors all carried information for viewers (or worshippers) and had symbolic value. It is only recently in the long history of human civilization that artists have created portraits of “regular” people, presenting them as they wish in works that are romantic, mean-spirited, comedic, flattering, lush, grotesque or bizarre.

The exhibition has a rich mix of every kind of face and every genre. As you walk among the art, you pass through various periods in time and styles of painting. In the images you see biting social commentary and witness love and hatred, satire and romance. And through these 70 portraits you see a picture of the late Soviet and post-Soviet period in Russian art and society.

Mugs and masks

The exhibition opens with powerful images. The first thing you see as you enter is the face of a god (or man?) and a red button — an interactive video by Platon Infante. Next your eye is caught by two enormous and boldly colored portraits by Natalya Turnova and several paintings by Oleg Tselkov, the renowned artist who passed away in Paris in July. Tselkov’s portraits of brightly colored, globular faces are both off-putting and mesmerizing. He called them “mugs” and said, “When I first painted my Mug — that’s what I called my strange hero — I was shocked. It wasn’t a portrait of a specific subject, but a composite portrait of everyone together in one face. And it was horribly familiar. This personage wasn’t attractive, but he drew people like a magnet and then gave them shivers. It wasn’t a face but physiognomy, a visage, and so dreadfully familiar.”

Turnova’s wall-sized portraits from the series “Passions,” painted nearly a half-century later, are stylistically different but, like Tselkov’s, have the same mysterious ability to morph from fierce to soft, or change in color, or seem to have different expressions as you stand before them.

All around these large paintings are a chorus of different images: Vladimir Yankovsky’s powerful head (1963), Vladimir Nemukhin’s portrait of a guitar-jack of diamonds; Vladimir Yakovlev’s touching “Portrait with a Cross,” and more than a dozen of Anatoly Zverev’s sketches and paintings of friends, neighbors and fellow artists.

Beloved faces

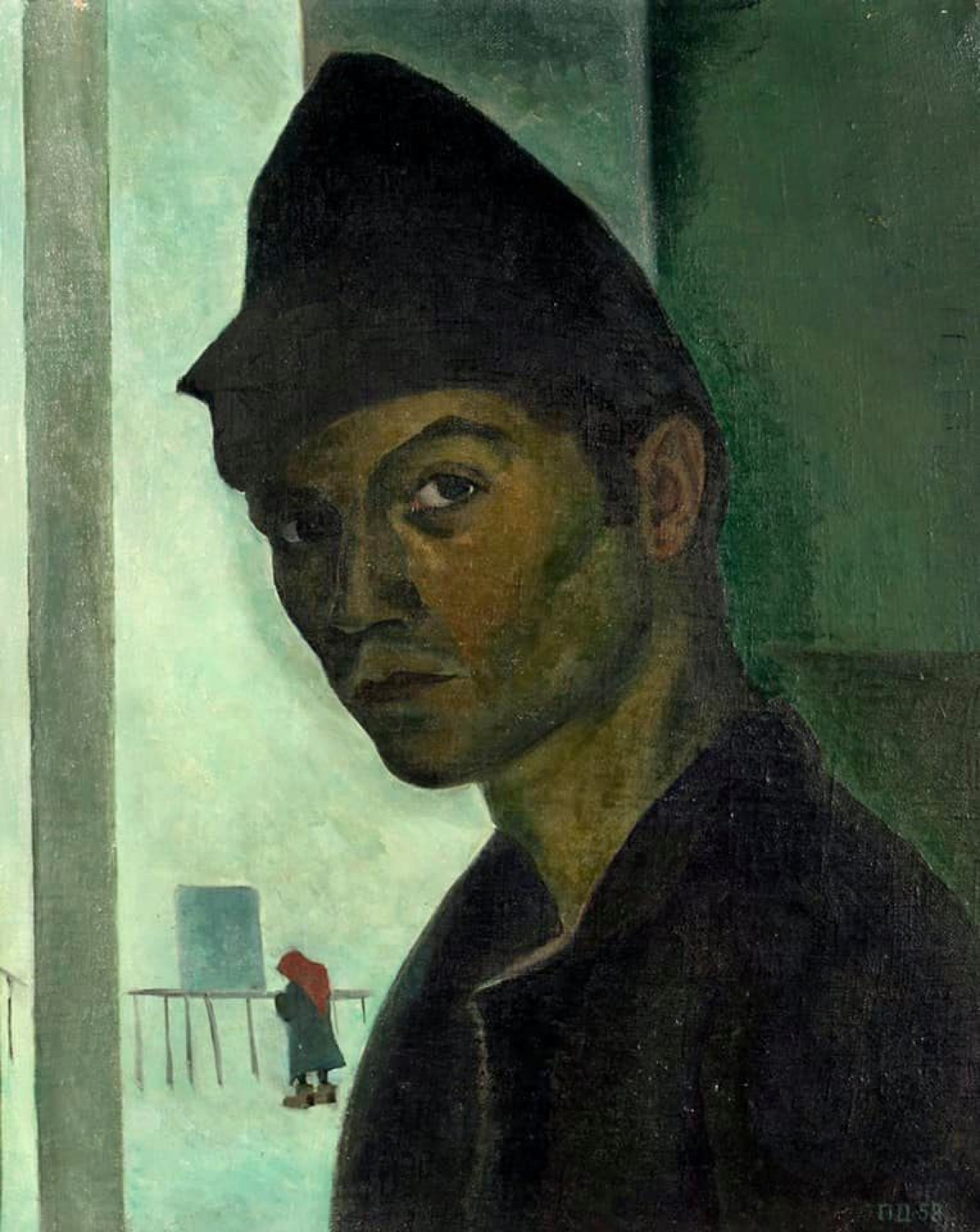

The second floor displays the great range of non-conformist art: lyrical, shocking, touching, odd, playful, haunting. The portraits begin with Mikhail Chemiakin’s whimsical-strange images and then move to the arresting self-portrait of the young Dmitry Plavinsky.

Grisha Bruskin’s “Cosmic Portrait” sculpture stands in the center of the room, across from Sergei Shutov's odd self-portrait: an impenetrable mass of swirls, bumps and hillocks that metamorphize into a face from across the room.

The third floor is all Zverev: his lyrical portraits of some of the most important women in his life —Polina Lobachevskaya (the museum art director); Inna and Natasha Costakis, daughters of collector George Costakis; and his beloved Oksana Aseyeva, the love of his life who was nearly 40 his senior, but whom he always painted as he saw her, a young woman. “You know, kid,” Zverev once said, “I make everyone beautiful...”

Across from the portraits is a mesmerizing lyrical video installation by Platon Infante that deconstructs and reconstructs Zverev’s works.

Head up one more floor to have coffee or a drink in the rooftop café overlooking the area around Triumfalnaya Ploshchad. Before you go, step into the yard behind the museum where the sculptor Vadim Kosmatschof’s sculpture of the AZ Museum logo rises in steel and whimsy up towards the sky.

For more information about the show and tickets, see the site here. The exhibition runs until Aug. 15.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.