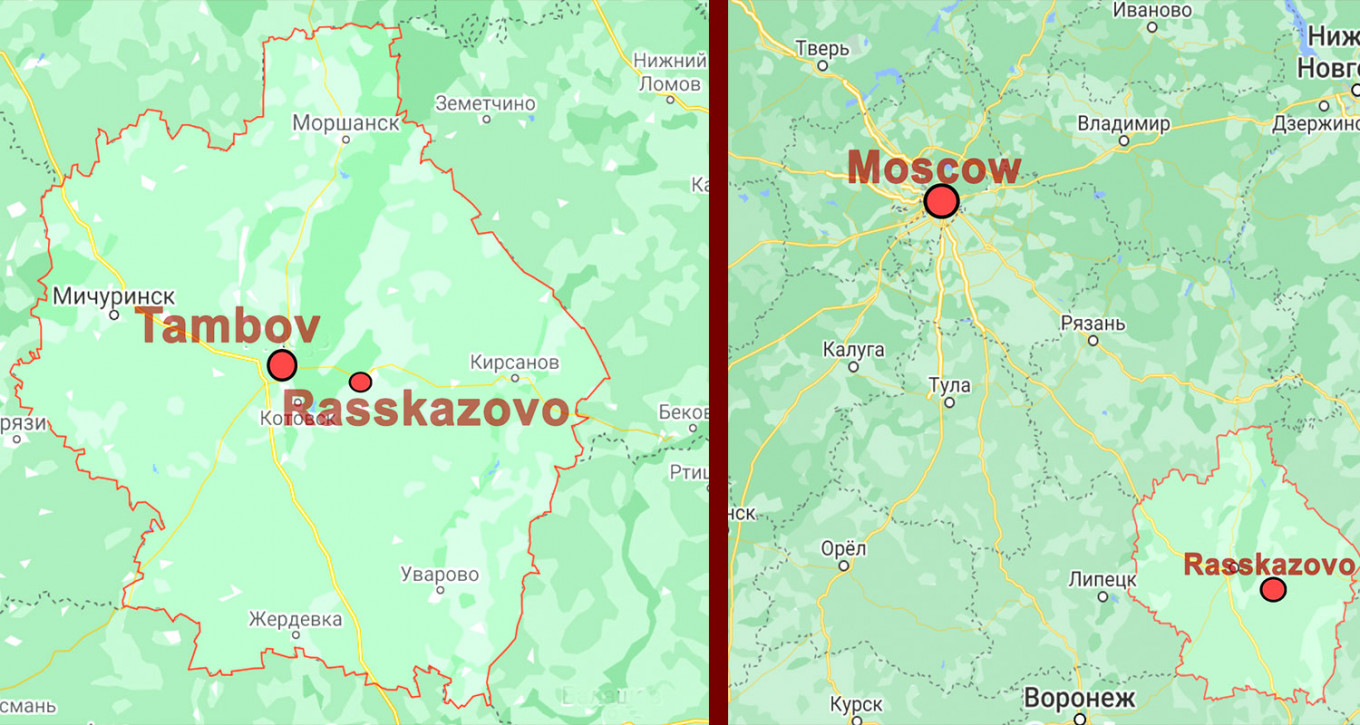

RASSKAZOVO, Tambov Region – In 2018, Sergei Kalinin decided to leave Moscow and go home to Rasskazovo, a hardscrabble, agricultural town of around 40,000 in central Russia’s Tambov region.

He rented out a vacant basement on the town’s central square and fitted it out as a chic, European-style coffee joint, complete with exotic blends and vinyl records. It was the first modern coffee shop in the town, and three years on business is booming despite the pandemic. There’s just one problem.

“It’s virtually impossible to get staff,” said Kalinin, 28, who is one of only a bare handful of classmates who have returned to Rasskazovo since leaving school.

“Almost all the young people leave as soon as they can, and those who stay aren’t interested in working.”

Rasskazovo, where the average monthly salary is around 18,000 rubles ($240), is far from unusual in rural Russia, much of which is plagued by a youthful exodus.

But in the Tambov region — an agricultural province home to some of the world’s most fertile land — the crisis is especially acute. This year, the region registered the fastest decline in population of any in Russia, losing almost 4% of its inhabitants in the two years up to 2020, according to state news agency RIA Novosti.

Since President Vladimir Putin came to power in 2000, Russia’s shrinking population has been a hot political topic.

In 2019, at his annual press conference, the Russian president admitted that the prospect of a depopulating Russia “haunted” him.

Though worst case scenarios have been averted amid modest rises in fertility — in part promoted by Kremlin policy including cash payouts for second children — Russia’s population has stubbornly refused to increase, leveling out at around 146 million people.

In 2018, the country’s population entered into decline after almost a decade of expansion as the generation born in the 1990s — a decade when people held off having children because of economic and political upheaval — began to reach childbearing age.

With trends accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic — during which Russia has registered almost half a million excess deaths — the Kremlin now expects the Russian population to shrink by 1.2 million by 2024, according to the RBC news site.

But with Russia’s largest cities still registering healthy growth, the demographic crisis is falling disproportionately on the poorer, rural areas where around a quarter of Russians live.

With average salaries in rural Russians around half those of the cities, and life expectancy around two years lower in the countryside, the temptations of urban life are clear.

“In many ways, what we’re seeing now in Russia is what happened in Europe sixty years ago,” said Nikita Mkrtchyan, a geographer studying rural Russia at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics.

“People are leaving the villages and still haven’t found a reason to return,” he said.

According to a 2018 study co-authored by Mkrtchyan, each year around 200,000 Russians abandon rural areas for the cities.

As a result, nearly 100 million of Russia’s 222 million hectares of agricultural land have fallen into disuse, according to a 2016 land-use survey.

Heavily composed of young, working-age people, the rural exodus has hit towns like Rasskazovo hard.

Situated in the hyper-fertile Chernozem, or “Black Earth” region, Rasskazovo has always been squarely in Russia’s agrarian heartland.

Around the town, lush corn and sunflower fields spring from the pitch-black soil — rich in natural fertilizers like ammonium and phosphorus — from which the region takes its name.

In recent years the Kremlin — with an eye on increasing grain exports — has announced ambitious goals for increasing agricultural output in Russia’s Black Earth breadbasket.

But in Rasskazovo itself — the name translates as “Storytown” — there are few signs of a rural renaissance.

Having comprised 50,000 people as recently as the mid 1990s, Rasskazovo’s population now declines by around five hundred people, or one percentage point, each year, according to Rosstat data.

Once a wealthy hub of the textile industry growing flax to clothe workers in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Rasskazovo is now visibly emptying.

In the town’s historic center, both low-rise Soviet housing blocks and grand villas built by nineteenth-century merchants lie derelict and decaying.

Around the town, posters advertise shift work in Moscow for underemployed locals, promising free food and accommodation on the job.

“The young people don’t stay here,” said fifty-eight-year-old Nina Koshkovskaya, a curator at the local museum.

“Some go to Tambov, some go to Moscow.”

It’s a situation mirrored in the wider Tambov Region, where the local population — almost three million in the 1920s — this year slipped beneath one million, around a third of them pensioners.

For experts, the Russian countryside’s woes are in part a legacy of the Soviet collapse.

In particular, they blame the collapse of the collective farm system, whose labour forces were often bloated, for dealing a death blow to towns like Rasskazovo, which is today surrounded by the abandoned kolkhoz collective farms that once fed the region.

“Soviet agriculture wasn’t exactly efficient,” said geographer Mkrtchyan. “But it did provide plenty of jobs to sustain rural areas.”

By contrast, the large agribusinesses that now operate many of the former collective farms employ slimmed down labor forces that are unable to support rural communities.

For many observers of Russian rural life, a further blow to the countryside has been the decline of the expansive, if threadbare, Soviet welfare state.

A wave of cost cutting measures in the 2000s halved the number of hospitals in Russia in optimization measures that disproportionately affected rural areas.

“It can be hard to live in the villages,” said Mikhail Shkonda, a rural affairs activist at the Association of Peasant Smallholdings advocacy group. “There are always problems with infrastructure, roads, and access to the internet.”

Ties that bind

It’s a story that rings true in Rasskazovo. Where the town once supported eleven schools, cuts and population outflows have left it with only two.

Even so, for those who have chosen to stay in the town, there are still ties that bind them to their dying hometown and its bucolic way of life.

“I like it here,” said cafe owner Kalinin. “If I just get on my bike, I can cycle off into the forest and be totally alone in five minutes.

“You can’t do that in Moscow.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.