At 10:40 a.m. on July 28 Mrs Justice Tipples entered Court 4 of the Royal Courts of Justice in London. We all rose, and one of the most important libel cases in recent times began. It has far-reaching implications for freedom of expression and the institutions that sustain it.

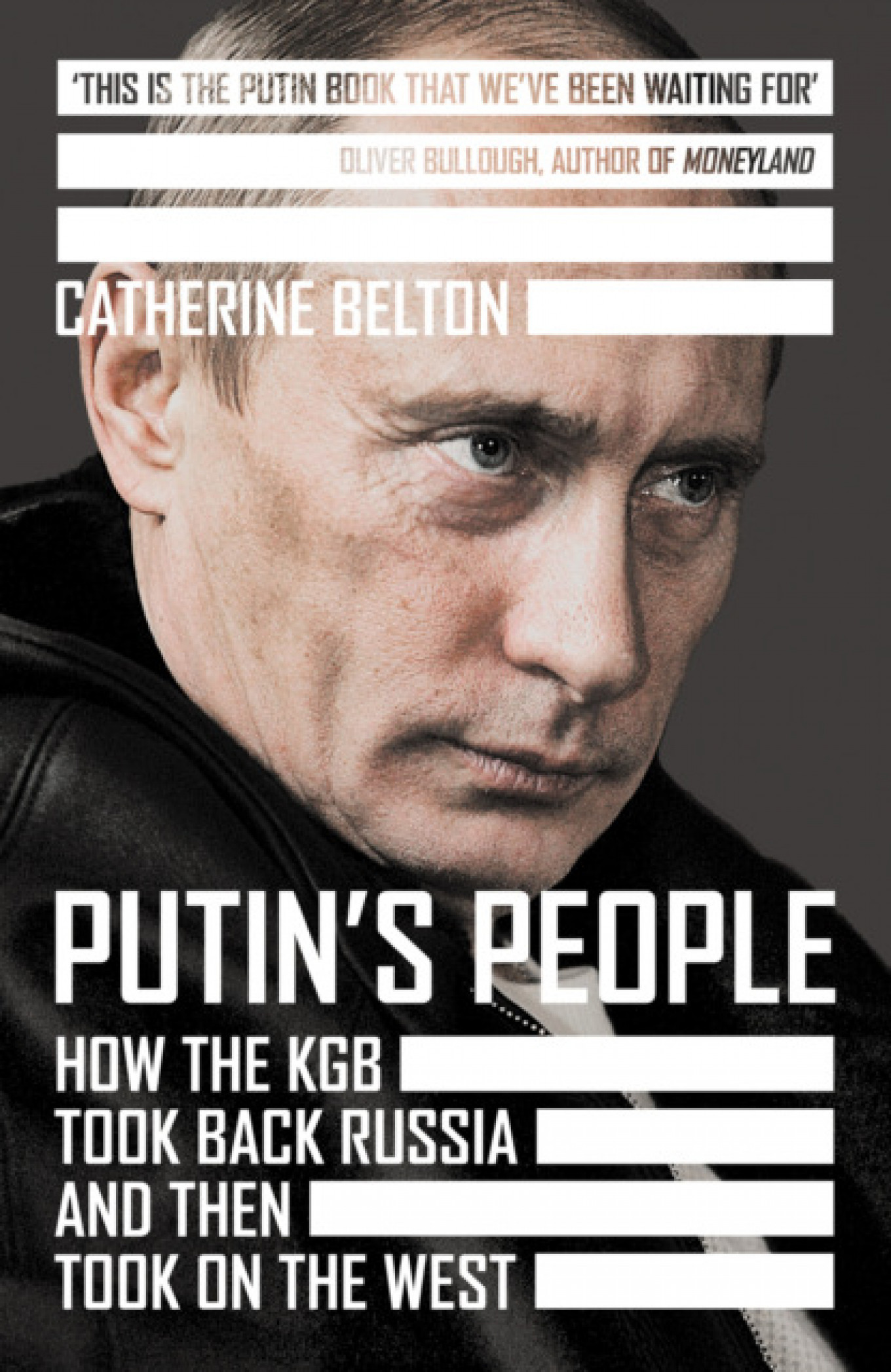

The trial concerns “Putin’s People” by Catherine Belton, the most meticulously documented account yet of the rise of Vladimir Putin and his circle from the chaos of the early 1990s to authoritarian rule in the Kremlin. It was published last summer to widespread acclaim. Close to the deadline, several oligarchs — a group for whom a collective noun has yet to be coined — as well as state oil company Rosneft brought libel actions against publisher HarperCollins, and in some cases Belton personally, and invited us to believe these actions were uncoordinated.

For those more versed in Russian politics than court process, the first day offered bemusing moments. Learned counsel dissected the habits and dispositions of that hypothetical yet indispensable creature, the “ordinary reader.” Does the ordinary reader finish a book? Would he — when gender was specified, it was always “he” — remember who Roman Abramovich was if he did so? Does he use the index? Is he a fan of Le Carré?

Counsel for Abramovich expounded on “how to read a book.” The defence replied that there were meanings of impressions and meanings of context, invoking “Wagner’s operatic leitmotifs” to clarify matters. “Context is everything” was the conclusion. At this point some of us might have wished a copy of “Deconstruction for Dummies” was at hand.

A major test of English law, and the principles of freedom it embodies and protects, underlie these rarified arguments. For years, libel law was criticised for favouring claimants and thereby encouraging the powerful from around the world to suppress their critics in London. The 2013 Defamation Act sought to create a more level playing field, in particular by introducing a test of “serious harm” and a public interest defence. Yet the “Putin’s People” cases, funded from bottomless pockets, have found their way to court. The assertions they dispute are at least two decades old and unlikely to astonish any serious student of Russia. It is difficult to imagine them causing the “serious harm” required by the 2013 Act.

It is hard, too, to see what the claimants stand to gain by bringing these actions – assuming, that is, that it was their idea to do so. The trial and attendant publicity are certain to make the book and its arguments known to a far wider audience of “ordinary readers.” The larger purpose of this unprecedented action is almost certainly to deter reporting, writing and publishing on matters of legitimate interest about Russia. Over the past year, domestic repression within Russia has risen sharply. Now, it seems, there are new efforts to intimidate opinion abroad. The chosen instrument is English law, and those hired to wield it include a leading human rights chambers.

This is an urgent public policy issue for Britain, and other open societies, faced with systemic competition from authoritarian states. Elites in regimes that threaten the West have long enjoyed access to financial, legal and property systems that protect their wealth. As a consequence, the West’s openness has helped to sustain adversary states. The “Russia Report,” released a year ago by Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee, began to draw attention to this contradiction. The Integrated Review published in March this year echoed its concerns. Neither went far enough. The “Putin’s People” affair raises the stakes: Oligarchs are now not just enjoying Western freedoms but, through vexatious litigation, using these to try to suppress the freedom of others to write about Russia.

A victory for the claimants would have a chilling effect on those reporting and writing on matters of legitimate public interest. It would also embolden similar litigation from Russia and elsewhere. The case for exploring further legal reform to prevent such cases being brought in future is strong. So is the case for Anti-SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public participation) legislation to prevent suppression of legitimate reporting with the threat of financially ruinous legal actions.

Such steps should in turn be part of wider efforts by democracies to meet the growing challenge of systemic rivalry on the home front as well as abroad. This means adapting institutions and practices across many domains to ensure democracies remain open and strong while preventing others from using these freedoms to undermine security and values from within. The great-power rivalries now unfolding may ultimately be decided not by the balance of power or resolve, but by the balance of resilience.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.