An enormous exhibition called “Andy Warhol and Russian Art” opened last week at the expo center Sevkabel Port in St. Petersburg.

The show, organized by the Artsolus Foundation, displays 100 works by Andy Warhol, one of the founders of pop art, along with works by such important Russian artists Alexander Melamid, Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, Pavel Pepershtein, and the group RECYCLE.

At the center of the show is not just Warhol and the myths surrounding him, but how those myths influenced Soviet and Russian art. For people living in the consumer society that is contemporary Russia, the show draws their attention to artists and aspects of everyday life that they no longer notice. For example, rows of different colored lipsticks — red, pink, lavender — done in applique by Zina Isupova. Or sculptures of food delivery couriers. Or images of Marilyn Monroe or Lyubov Orlova, the star of Stalinist cinema embodied by the artist Mamyshev-Monroe.

The exhibition makes clear what an enormous influence this American artist had on Moscow conceptualism — which may be considered the highest expression of socialist realism — and shows the constant dialog between Warhol and post-Soviet artists. But the great appeal of the exhibition is that it showcases many fine original works, not only by Warhol — whose works are more or less familiar — but by contemporary Russian artists. Warhol, who until recently was considered by many to be nothing but an unintelligible dauber of little talent, is revealed here as a great innovator who opened the path to a new kind of art.

The show consists of nine spaces. The first space is an attempt to recreate the so-called “Warhol Factory,” the space in New York where Warhol lived, worked and welcomed a very wide variety of guests, some rather outrageous figures, like Mick Jagger whose portrait is here.

The other eight spaces — I’m a Brand, Sculptures, Consumption, Animal Protection, Fame, Money, Famous Jews, and Epilogue: Memento mori — are interesting primarily for how they illuminate the connection between Warhol and Russian artists. Warhol’s famous portraits of Mao Tse Dung are hanging by Boris Yeltsin in blurred and sharply focused photo-images created by Mikhail Zotov.

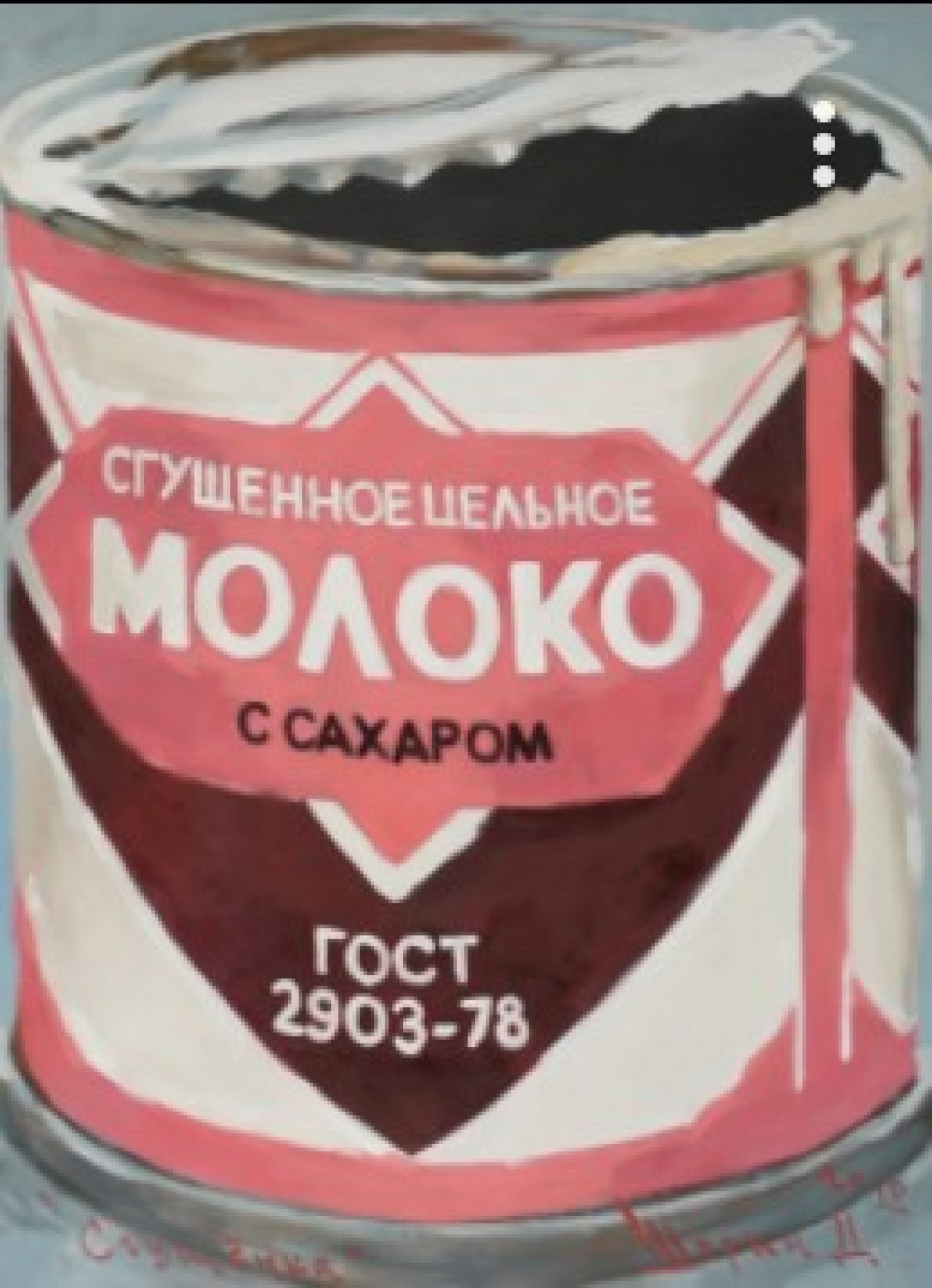

In another place Warhol’s soup cans are juxtaposed with Dmitry Shorin’s open can of Soviet sweetened condensed milk and the wrapper for black caviar that another Russian artist considered a work of art. The Moscow artist Viktor Ponomarenko painted a stylized still life of a McDonalds bags and plastic cups in the style of old Dutch master — a disconcerting combination of humor and philosophy.

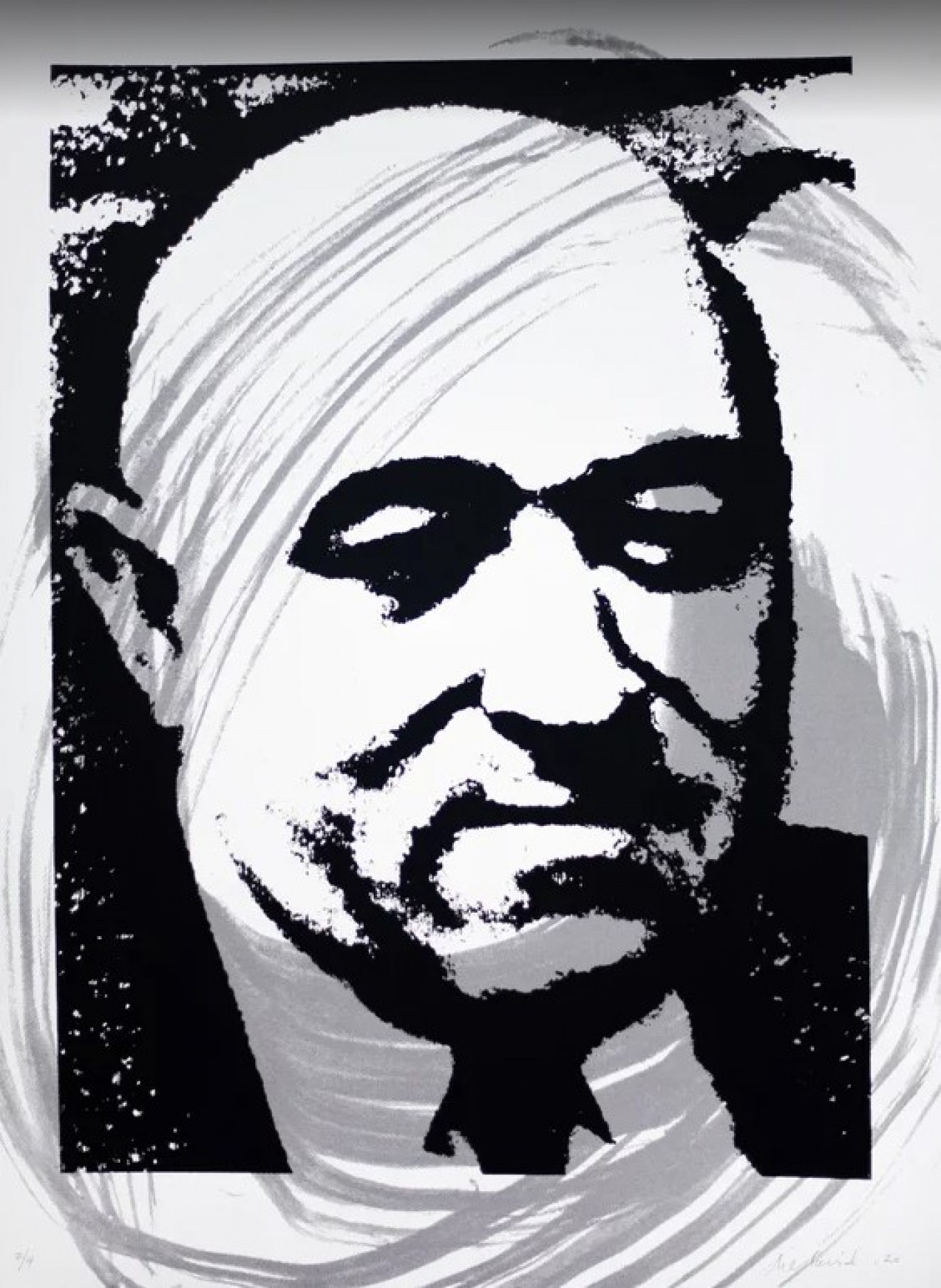

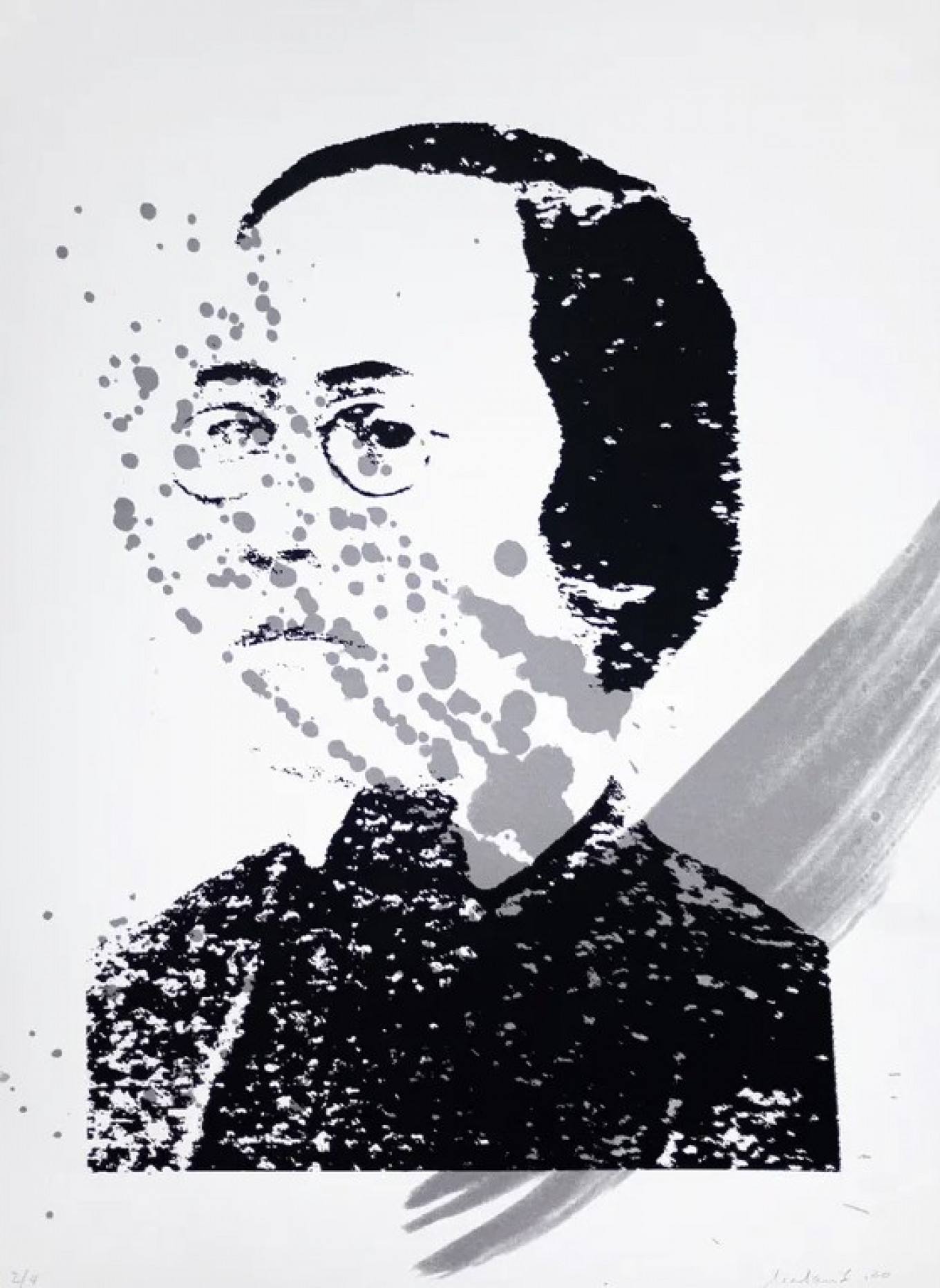

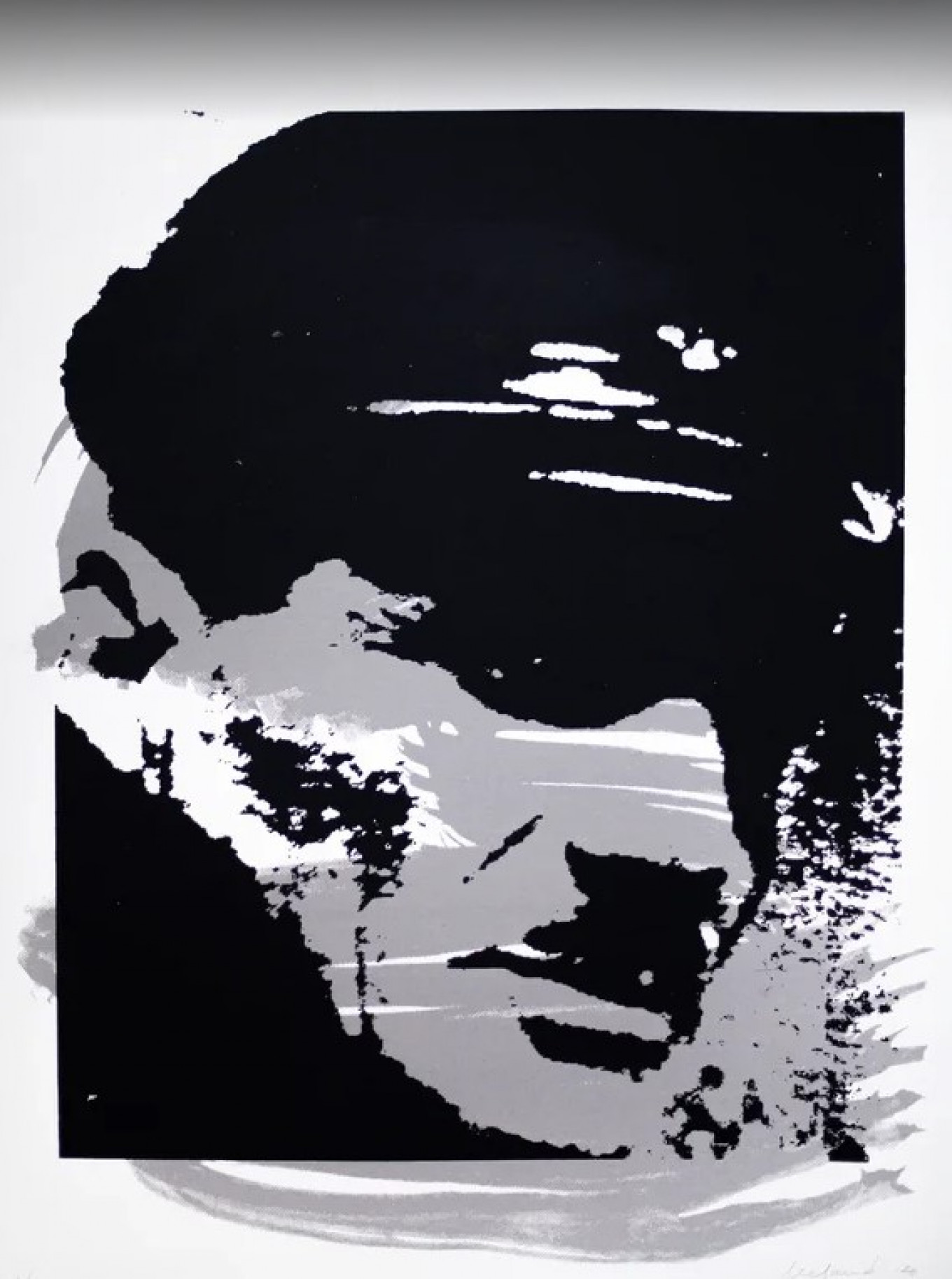

Artist Alexander Melamid responded to Warhol’s famous series “Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century” — a group that include Sigmund Freud, Frans Kafka and Golda Meir — with his own series. However, if Warhol chose heroic Jews, Melamid chose the opposite. The series of silkscreen on cartonnage portraits, called “Ten Other Jews of the 20th Century,” are of American gangsters as well as communists and chekists (security agency officials) of the Stalinist era. The Americans — Bugsy Siegel, Meyer Lansky and David Berkowitz (the “Son of Sam” killer) — are not well-known in Russia, and neither, judging by the reactions to the portraits, are some of the Soviet-era figures.

The first portrait is of Matyas Rakosi, the man who ruled post-war Hungary and was called “Stalin’s best student.” He copied the Stalinist model of governance, wiping out any form of dissent, fighting against the Catholic Church, and starting a campaign against Zionism in the late 1940s. A true son of the U.S.S.R., he was extremely displeased by the decisions of the 20th Congress to de-Stalinize the country. He ended his days in the Soviet Union with his wife, Feodora Kornilova, who was from Yakutia. In Budapest the Museum of Terror displays portraits, too — of the victims of communist repression under Rakosi.

The series includes Lazar Kaganovich, who was a brutal taskmaster while building the Moscow metro in the 1930s. There are still stations where you can glimpse his name, now covered over with plaster and paint. In Melamid’s portrait he is slightly faded. Melamid also included Naftaly Frenkel, a prisoner who became an NKVD general for advising Stalin to use prisoners in the Gulag for construction work.

One of the least well-known among exhibition visitors is Julia Brystiger, although she is very well known in Poland as an officer of the secret police after WWII. She led a campaign against the Roman Catholic Church, using torture and violence against priests. For her portrait Melamid used the best-known photograph of Bristiger, her eyes burning with fervor. Bristiger, called “Bloody Luna,” brought Stalinist order to post-war Poland.

Another villainous woman in Melamid’s portrait gallery is Rosalia Zemlyachka, who is notorious in Russia as the person who organized the mass execution of White Army officers and aristocracy in Crimea in the 1920s. In the portrait Zemlyachka’s face — cruel eyes behind her pince-nez —seems to be marked with a tire tread.

Alexander Melamid comes from a family of celebrated Soviet historians: Lyudmila Chernaya and Daniil Melnikov, Germanists and authors of the first Russian biography of Adolph Hitler “Criminal No. 1.” In an interview from New York, Melamid told The Moscow Times that he hadn’t heard about the people he portrayed from his parents. In fact, he doesn’t remember them ever mentioning their names. He chose them after searching online.

“I didn’t have any special knowledge of them,” he said, “I was drawn to their physical expressiveness.” And he said that in many cases these were people who were responding to the unique historical conditions they found themselves in. General Naftaly Frenkel “survived in those conditions and is now immortalized in a work by Melamid,” he laughed. “My theory is that there aren’t bad people, but a person with a particular character falls into particular circumstances.”

Melamid said that these portraits are images of “extremely unpopular people,” and for that reason his art, and especially this series, is the opposite of pop art. It’s hard to explain this to people in the West, he said, but eliminating them from history is impossible. Melamid said he is negotiating for the portraits to be displayed in Israeli museums, but there are all kinds of issues about portraying these particular historical figures.

By world view, “I’m a confirmed skeptic,” he said. “And for a skeptic the most important thing is to refuse to agree with any opinion. It’s very difficult, but if you can do that, you will attain absolute happiness,” he said.

The series was not done especially for this exhibition, but when the Moscow curator Andrei Yerofeyev heard about them, he did everything in his power to include the works in the show and catalog.

The show ends with two black and white canvases facing each other from opposite walls with space for exhibition visitors in between them. On one wall is Elvis Presley dressed as a cowboy pointing a gun at the visitors. Across from him are executioners of the NKVD with red stars on their caps shooting back.

The show will run until September 19. For more information and tickets, see the exhibition site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.