Russia’s bureaucracy has become obsessed with the concept of registers. There are registers for everything, and every month new registers appear.

There are registers for all the bad things in the country, including an infamous blacklist of websites and pages maintained by the Internet censorship agency Roskomnadzor. There is also a register of entities deemed to be extremist and terrorists administered by the Justice Ministry — the one Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation was recently added to.

There are registers for good things too. This month, the government announced plans to introduce a unified register of companies and entrepreneurs engaged in innovation and receiving government support. There is also a register of all companies working for the military industrial complex, and a national register of Russian software.

There are also registers of the approved versions of knowledge and ideas, like the federal register of textbooks, maintained by the Education Ministry.

Finally, there are registers for things the government wants to keep an eye on, and the list of these keeps growing.

Only in June, the country’s internet censorship agency Roskomnadzor got the go-ahead from the Duma to launch six new registers listing foreign internet resources that are significant for Russians, foreign websites to which money transfers are prohibited, foreign payment systems serving prohibited sites, sites whose audience is to be measured, advertising data operators and cross border cables.

Registers are not limited to politics or the tech industry. Two months ago, chairwoman of the upper chamber of the Russian parliament Valentina Matvienko supported a proposal from the Justice Minister to create a unified national register of non-payers of child maintenance in Russia.

Where does this obsession with lists and registers come from? Why is it so important for the Kremlin to put everything — from bad to good to strategic or sensitive or dangerous — on some sort of list and have a specially assigned agency to maintain it?

Technology is partly to blame, as a large amount of data makes a government obsessed with the idea of control look more efficient. If traditional bureaucracy fails, as it usually does in Russia, digitalization is there to fix things, or so the Kremlin’s technocrats tend to believe.

To give an example, schools cannot be trusted to choose what kind of computers they should acquire, so they are made to choose from a register of radio electronic products maintained by the Ministry of Industry and Trade.

The obsession with registers has also a definite feeling of the Chinese approach to social control. Once a person finds themselves on the wrong side of things they can expect to have their rights suppressed — including the right to a loan or a good job, which is very likely to happen to those who find themselves on the upcoming register of non-payers of child maintenance.

The blacklists are increasingly being shared between government agencies, and sometimes even private companies like banks and insurance companies, which makes the discrimination more totalitarian by the day.

But the concept of registers also encompasses the fundamental belief in the possibility of forming a final, exhaustive list of everything, from innovation to enemies of the regime.

According to this theory, new things should not pop up and become available spontaneously.

For example, if the government maintains a list of innovations or software, it means that new apps should be added to a national register before being accessible to ordinary people, after first being checked and assessed by wise men assigned by the government to be in charge.

This is exactly the concept one can find in the latest version of Russia’s Information Security Doctrine which stipulates that telecoms and IT companies should always consult with the secret services ahead of introducing new services and technologies for their customers, because the authors of the doctrine are unhappy with “the practice of introducing information technologies without first providing for information security.”

In turn, the Kremlin’s political rivals become enemies not because they did something, but because they landed on the list of enemies.

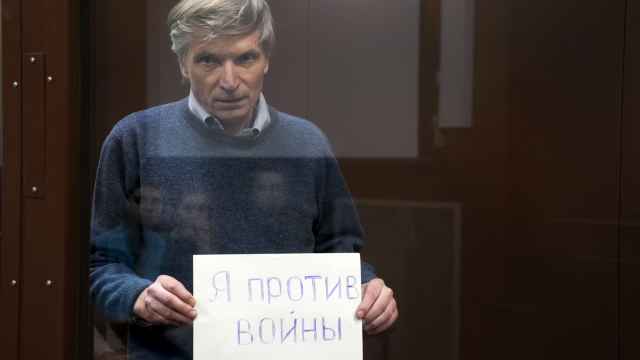

When the Kremlin took the Navalny foundation to court it didn’t want to have a Stalin-era show trial with a procession of witnesses denouncing Navalny and his supporters to change public opinion and intimidate. On the contrary, the trial was secret because its only purpose was to add the foundation to the register of extremist organizations.

In a nutshell, it increasingly looks like the government is instigating nationwide preliminary censorship to society. Ideas, technologies and even people begin to exist only after they have been added to a register maintained by the government.

Are you even there, if you are not accounted for?

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.