As Moscow grapples with a third wave of coronavirus, the thorny issue of vaccine hesitancy has emerged as the biggest roadblock to achieving that desired herd immunity. An overwhelming majority of Russians flatly refuse to get the widely available Sputnik vaccine, despite all inducements or mandates from the government.

This should surprise no one. A homegrown vaccine that is both free and widely available must by its very nature be suspect. If the Sputnik vaccine were imported, hard to get and/or in very short supply — that might get the masses flocking to empty vaccine pop-ups. At the mere suggestion of anyone lining up for anything, Russians are instantly motivated to work out a way to get to the head of the line. But as things are, most Russians I know plan to give Sputnik a very wide berth, until, of course, something truly urgent ultimately forces their hand.

How this will play out in the coming weeks is anyone’s guess, but what we can say for certain is that it will be an excellent time to be in the glass jar business. Because when faced with any kind of medical threat, Russians will always fall back on that one reliable remedy for all ailments, from a mild head cold to a highly contagious virus.

I refer, of course, to jam. Or rather, varenye, which is best translated “preserves,” as it contains large chunks of the fruit or whole berries with lots of syrup as opposed to firmer, English-style “jam,” which is made from crushed or pureed fruit. And this is never to be confused with “jelly” which in Russian more often than not refers to an aspic or molded fruit dish.

Varenye looms enormous in Russian culture and cuisine. In pre-revolutionary Russia preserving fresh fruit and berries for consumption during winter was one of the few ways Imperial Russia’s poorer peasants got sufficient vitamins, enabling them to survive prolonged deprivation from fresh produce. To this day, tea in Russia is traditionally taken with varenye rather than sugar, either served alongside, or spooned right in. Late spring and early summer arrive with old ladies selling berries in plastic buckets near metro stations, and no trip to see the older generation at their dacha is complete without a ceremonial opening of a jar of the hostess’s varenye.

This can be a slippery slope. Varenye can be quite an aphrodisiac — so much so that perhaps we should rename the classic Russian “honey trap” a “jam trap.” A friend recently recounted the details of an unfortunate male expat falling victim to a female Russian grifter, rather more interested in his bank account than his soul. “She lured him out to her dacha and clinched the deal with varenye,” my friend said, raising her eyebrows. “Typical.”

My own love affair with varenye began predictably at Leningradsky market, where an entire aisle is given over to the sale of every kind of varenye imaginable. It was here that I learned the Russian words for “blackberry,” “strawberry,” “red current,” “sea-buckthorn” and the all-important “raspberry.” Surveying the glittering rows of jewel-toned varenye, enjoying free samples proffered on tiny twists of paper, and ultimately choosing one or two to take home remains one of life’s great luxuries.

When a Russian falls ill, her first impulse is not to call the doctor, or even visit the pharmacy (unless, of course, the pharmacist is a trusted source of hard-to-find medicine), but rather to put the kettle on and reach for the jam jar. And, after two decades in Russia and many terrible colds and bouts of flu, I can attest that there are far worse ways to coddle a sore throat than with a jar of sticky sweet raspberry jam and a hot cup of tea.

So, while the science is crystal clear: varenye will not prevent, nor, indeed, cure COVID-19, making a batch is an excellent way to while away a day during lockdown. So let’s make some. Regular readers of this column will by now have braced themselves for the inevitable twist to this recipe or wonder what odd ingredient I will add to my varenye. Fear not. There are some things too sacrosanct even for me to mess with, and varenye is certainly one of them.

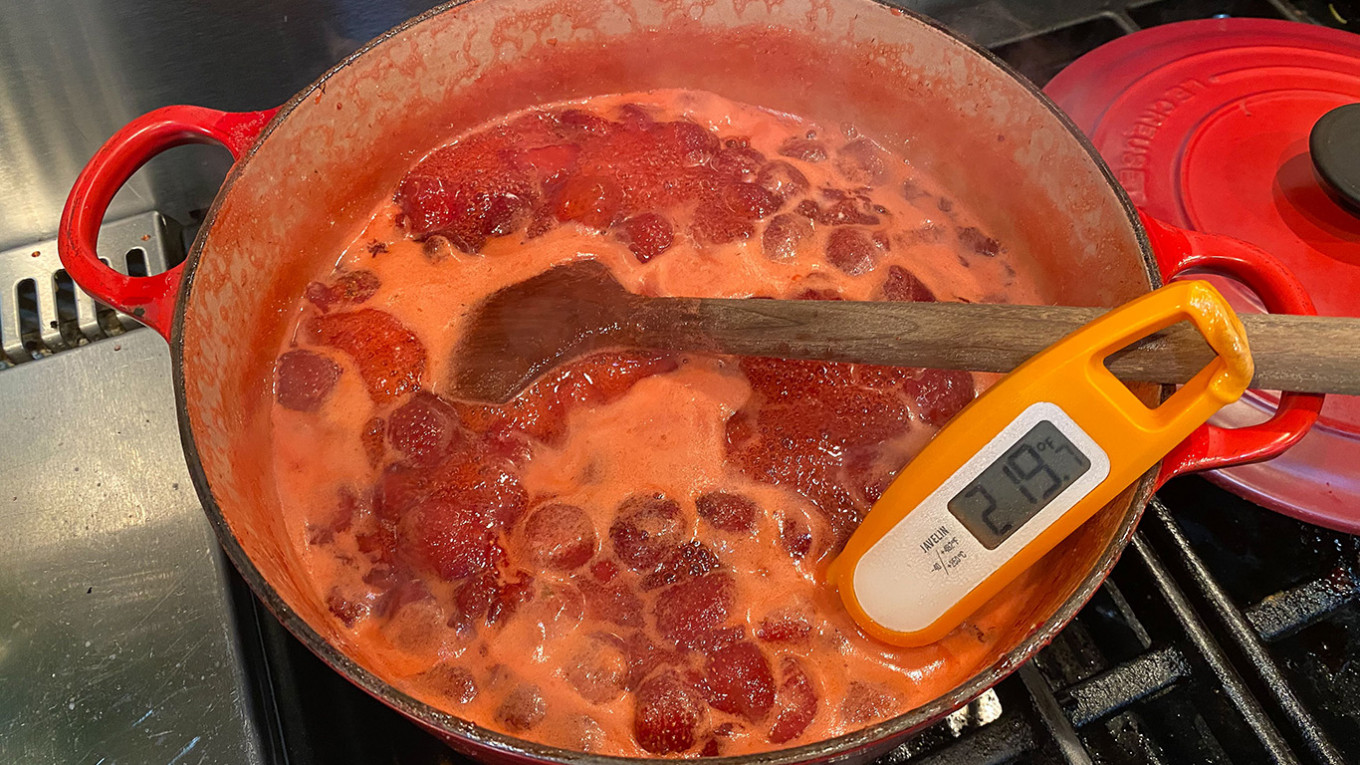

Strawberries are currently in season: the most challenging berry for jam makers because of its low amount of pectin, the long chainlike molecules in fruit that helps the jam to set. Adding acid, in this case lemon juice, helps the jam to set, and gives the final product a nice tartness to contrast the intense sweetness of the strawberries and sugar. The principal ingredient, however, is time: the varenye needs to simmer for at least 20 minutes until the temperature reaches 220ºF (104ºC). If you want to keep the jam for several months, you can freeze it or process it in a canning kettle. As is, the jam will keep in the fridge for about three weeks.

But it will not prevent Covid-19.

Classic Strawberry Varenye

Ingredients

- 2 pounds (900 grams) ripe strawberries, hulled and well rinsed

- 3 cups (700 ml) granulated sugar

- ⅓ cup (80 ml) fresh lemon juice

Instructions

- Place a small china plate in the freezer before you begin your preparations. This will help you determine if the jam has set when the time comes.

- Wash and sterilize glass jars and their lids.

- Place ½ pound of strawberries in a heavy-bottomed soup or jam pot and crush them with a potato masher. Add ¾ cup of sugar and bring the mixture to a slow simmer. Stir until the sugar has dissolved.

- Add the remaining strawberries, sugar, and lemon juice. Bring to a vigorous boil, stirring as you do to avoid scorching on the bottom of the pan. Maintain the boil for 10-15 minutes but begin to slowly lower the heat after 15 minutes, stirring frequently, and taking care that the jam does not boil over. The jam will thicken and reduce in size. If you have a thermometer, look for the jam to get to 220ºF (104ºC).

- To test for doneness, pull out that china dish you put in the freezer. When you think the jam is done, put a dollop of jam on the plate and put it back in the freezer for a minute. Drag a spoon or your finger through the jam; if the surface is wrinkled and the consistency feels like a gel rather than a liquid, the jam will set. If, however, the jam fills in the groove, then you need to return the pot to the heat for at least five more minutes.

- Decant the jam into sterilized jam jars, leaving ¼-inch headspace. Wipe the mouth of the jars with a clean cloth, then affix a sterilized lid. If you wish to keep the jars in your pantry for several months, immerse the filled jars in a water bath canner filled with boiling water and process for 5 minutes. Turn off the heat and leave the jars in the water for an additional five minutes. Remove the jars to a towel-lined rack and cool to room temperature.

- Alternatively, decant the hot jam into sterilized jars and cool to room temperature. Affix the lids, then freeze for up to 3 months or refrigerate for up to 3 weeks.

- If the finished product is too liquid, do not discard it! Either return the jam to the stove and boil it some more. Or use it as the base of strawberry lemonade or daiquiri or as you might maple syrup: spooned into yogurt or poured over pancakes.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.