CHERTANOVO — It’s 11 p.m. in a south Moscow hypermarket and Roman Yuneman is feeling philosophical.

“Either I’ll end up in jail, or on the ballot,” says the twenty-six-year-old independent candidate for Russia’s State Duma, over supermarket cafe sushi.

“I knew that sooner or later it would come to this. I just didn’t think it would be so soon.”

With under three months left until elections to the lower chamber of Russia’s parliament, the management consultant turned opposition politician is feeling the pressure.

Amid an escalating crackdown on Russia’s political opposition, Yuneman is one of a bare handful of independent candidates set to mount a real challenge to the pro-Kremlin United Russia party. That puts him squarely in the sights of a state that has already jailed or driven into exile a string of would-be candidates ahead of the September vote.

“I do sometimes wonder,” he says, “why on earth am I doing all this?”

Born in Germany in 1995 and raised in Kazakhstan by parents descended from Volga Germans deported to Central Asia under Stalin, Yuneman’s background marks him out even within the often-eccentric world of Russian opposition politics.

Growing up as part of an ethnic minority in new-born Kazakhstan was formative to a worldview he describes as “democratic nationalist.”

“My politics are based on two things. Firstly, I love my nation, the Russian nation. Second, I love freedom.”

Even so, he insists that his nationalism — the word carries a strong, Soviet-era stigma in Russia — is rooted in culture and language, rather than ethnic origin.

“I saw that even Russian-speaking Kazakhs were a thousand times closer to me culturally than Kazakh-speakers,” he said. “Anyone can become a Russian as long as they embrace Russian culture.”

After leaving Kazakhstan at eighteen to attend the Higher School of Economics, a prestigious Moscow university, Yuneman settled in Chertanovo, a working-class suburb of ageing, Soviet-era highrises on the capital’s southern outskirts.

An hour’s Metro ride from Moscow’s wealthy center, where anti-Kremlin opposition is always in fashion, down-to-earth Chertanovo’s 400,000 residents have traditionally voted overwhelmingly for Russian President Vladimir Putin and his United Russia party.

After a year at U.S. management consultancy Boston Consulting Group, Yuneman — who had always wanted to enter politics — decided in 2019 to run for the Moscow City Duma in his new home.

“I wanted to prove that not everyone who lives out here is happy with the way things are,” he said.

Political appetite

On polling day, as opposition insurgents felled pro-Kremlin incumbents all over Moscow, he drew 9,561 votes. His United Russia opponent took 84 more, a defeat Yuneman attributes to fraud via an electronic voting system trialled in the district that year.

However, the 2019 defeat only whetted Yuneman’s political appetite. Within months, his sights were set on a seat in the tightly controlled and Kremlin-loyal State Duma.

Raising over ten million rubles ($137,000) from donors, the Yuneman campaign has swollen to proportions rarely seen in Russa’s hollow, choreographed politics, hiring 45 full-time staffers.

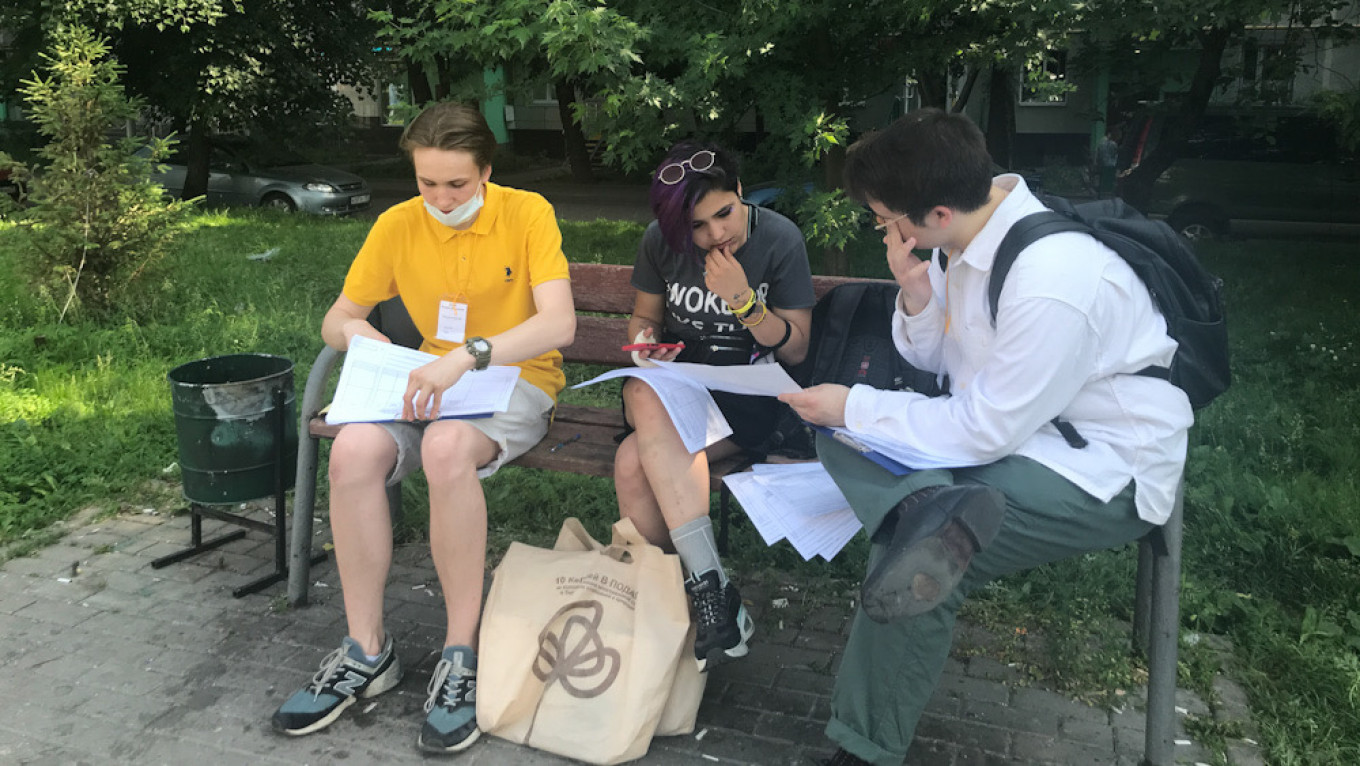

In the run up to the Duma election, hundreds of Yuneman activists — most still students — flood into down-at-heel Chertanovo each day to canvass voters.

According to a May survey by the independent Levada Center pollster, 5% of Muscovites approve of Yuneman, while another 8% disapprove of the young man who is all but unknown outside Chertanovo.

By any measure, Yuneman’s politics place him firmly on the hard right.

Among his intellectual influences he counts radical libertarian writer Ayn Rand and Konstantin Krylov — a prominent Russian nationalist activist who was convicted of incitement to racial hatred for a 2011 speech denouncing Caucasian immigration to Russia.

At his meetings, Yuneman flies the pre-1917 Tsarist Russian flag, in memory, he says, of a golden age in the country’s chequered history.

Among his long-term proposals is a visa-free regime with European countries, to be offset by clamping down on immigration from Central Asia and the Caucasus.

But on the doorsteps of south Moscow, the Yuneman team keeps nationalist ideology to a minimum.

“People aren’t massively interested in talking about immigration,” said Maria Musaeva, a 22-year-old kindergarten teacher turned Yuneman field coordinator, herself the granddaughter of Azerbaijani migrants.

“We try to keep the narrative as local as possible.”

Instead, Yuneman’s four hundred or so canvassers keep a tight focus on local issues: campaigning for a new metro station, better polyclinics and the preservation of neighbourhood parks.

As a result, says the Yuneman campaign, its internal data shows 20% of residents recognizing their candidate, an unusually high figure for a local politician.

Even so, getting on the ballot is no easy task.

Independent candidates for the State Duma have forty five days to gather 15,000 signatures from voters registered in their district, a high bar that has dissuaded all but a handful of contenders from running.

For the 400 or so activists who gather signatures for the Yuneman campaign at 300 rubles ($4) each, one of the biggest problems is voters’ suspicion of politicians of all kinds.

Many suspect a scam, worrying that their information will be used to take out a fraudulent loan in their name.

Even so, after four days gathering signatures, the Yuneman campaign had chalked up 3,000 nominations, putting him on track to make the ballot.

With apathy rife, retired older women or babushki — always the most likely to vote in Russian elections — are among the keenest signatories. Many have come to recognise a candidate who has been pounding the local pavement for three years now.

“Yuneman, that’s the German lad?” said Galina, a 77-year-old pensioner relaxing in a local park, when approached by the candidate’s canvassers.

“I liked him last time. And the one who beat him has vanished without trace,” she said as she signed the nomination papers.

On the campaign trail, one name in particular is almost never mentioned: Alexei Navalny.

With the jailed Kremlin critic’s organizations banned as “extremist”, anyone expressing even rhetorical support for Navalny is at risk of up to six years in prison.

In some ways, the taboo on Russia’s most prominent nationwide opposition figure suits Yuneman’s hyper-local campaign.

“We just need to keep quiet and get our job done out here,” he said.

“Then hopefully no one will come after us.”

Even so, with the September polling day approaching, the campaign is beginning to feel the heat.

With United Russia’s polling mired at around 30% — barely half of what it drew in 2016 — the Kremlin has moved to disqualify opposition candidates with a chance of defeating government-backed contenders, relying on a mix of targeted legal prosecution and outright intimidation.

In June, former State Duma deputy Dmitry Gudkov fled Russia, claiming that he had been told he would be arrested if he continued with his plans to run in the September election.

So far, however, the Chertanovo district has fallen somewhat under the authorities’ radar.

Though United Russia-affiliated hecklers have shown up at campaign meetings, and anonymous Telegram channels have spread rumours that he is backed by the Kremlin, Yuneman says he has received no threats from the security services.

Even so, he is only too aware that being an opposition candidate is a perilous career move in contemporary Russia.

“I’ve been ready to go to prison since I first started running,” he said.

Even so, Yuneman takes some comfort from the fact that, whatever the outcome of his current race, at twenty-six his political career is only just getting started.

“It’s like when you dive into a swimming pool from a great height. You know you won’t die, but you’re still frightened,” he said.

“It’s scary, but whatever happens, time is still on my side.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.